Introduction

The narrowing or occlusion of the external opening of the lacrimal canaliculus leads to punctal stenosis. This should be distinguished from punctal agenesis, which is a congenital condition (Fig 1). It may also be associated with occlusion of the common canalicular duct. Patients usually present with symptoms of excessive tearing. The incidence of this condition is variable, ranging from 8% to 54.3%.[1]

Anatomically, lacrimal puncta are located at the nasal end of the palpebral margin. The upper punctum is located 1mm medial to the lower punctum. Upper and lower puncta approximate each other when the eyelids are closed. The puncta open into the tear layer and lead into the lacrimal duct, lacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct. The papillae containing the puncta are surrounded by the Riolan muscle fibers and a fibrous ring. Normal punctal size ranges from approximately 0.2-0.5mm.[2] One study determined the criteria for punctal stenosis: the punctum is less than 0.3mm, or there is an inability to cannulate the punctum with a 26G cannula without dilation.[3] Based on the shape of the external punctum, punctal stenosis is of four types:

- Membranous (31%) Fig 2

- Slit type (13%)

- Horseshoe (31%)

- Pinpoint (32%)[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

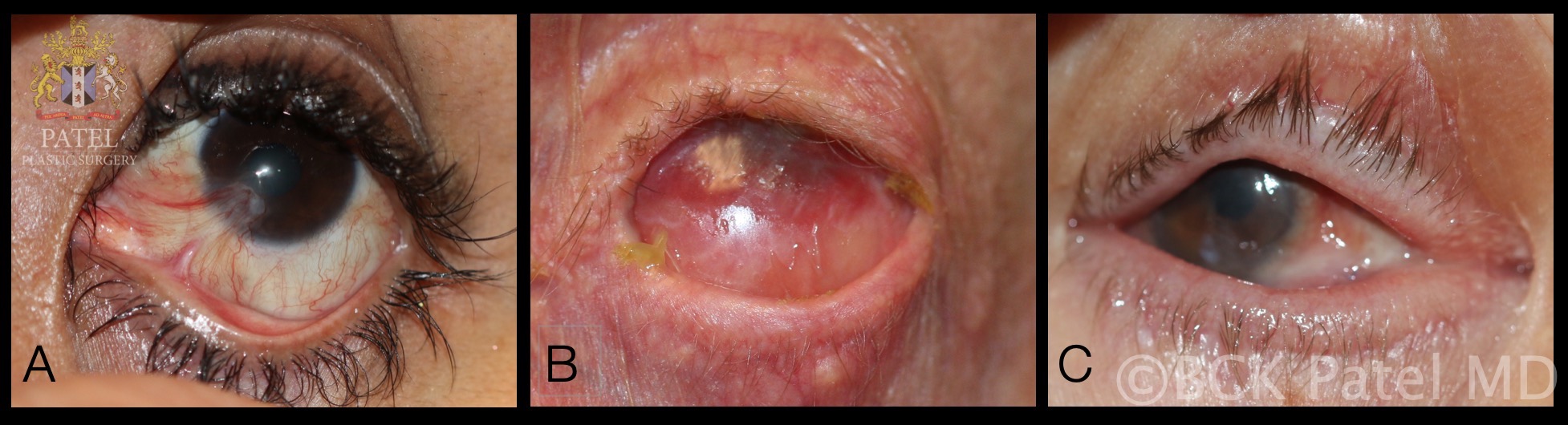

Punctal stenosis can occur due to a wide range of causes. The most common cause of punctal stenosis is chronic blepharitis (45%). Other causes include unknown etiology (21%), ectropion (23%), and drug-related (5%).[5] Eyelid infections like herpes simplex and trachoma are known risk factors for this condition.[6][7] Inflammatory conditions like benign mucous membrane pemphigoid disease and Stevens-Johnson syndrome also cause punctal stenosis. (Fig3 and Fig 4)

The use of topical antiglaucoma medication such as timolol, latanoprost, betaxolol, dipivefrin hydrochloride, echothiophate iodide, and pilocarpine pose a risk for the development of punctal stenosis as well.[5][8] The use of the systemic chemotherapeutic medications 5-fluorouracil and docetaxel are known to increase the risk for punctal stenosis.[9][10][11]

Epidemiology

The risk of punctal stenosis increases with age. In a study conducted to detect the prevalence of punctal stenosis in patients visiting the general outpatient department, 54.3% of the patients had punctal stenosis.[1] However, it should be noted that not all patients who are diagnosed as having punctal stenosis will be symptomatic. The mean age is approximately 69.4 years, with an age range of 39 to 90.[5] No gender or racial predilection has been found.

Pathophysiology

The normal punctum is chronically exposed to irritant substances in the tear film. In most patients with punctal stenosis, there is inflammation caused by blepharitis, chronic exposure (ectropion), or an external irritant (medications). Pathophysiological changes involved in punctal stenosis include chronic inflammation (36.7%), leading to fibrosis (23.3%), and squamous metaplasia (10%). Actinomyces israelii canaliculitis is responsible for inflammatory stenosis in 6.7% of cases.[12]

Histopathology

Histopathological examination of specimens has revealed chronic inflammation, fibrosis, or both.[12]

History and Physical

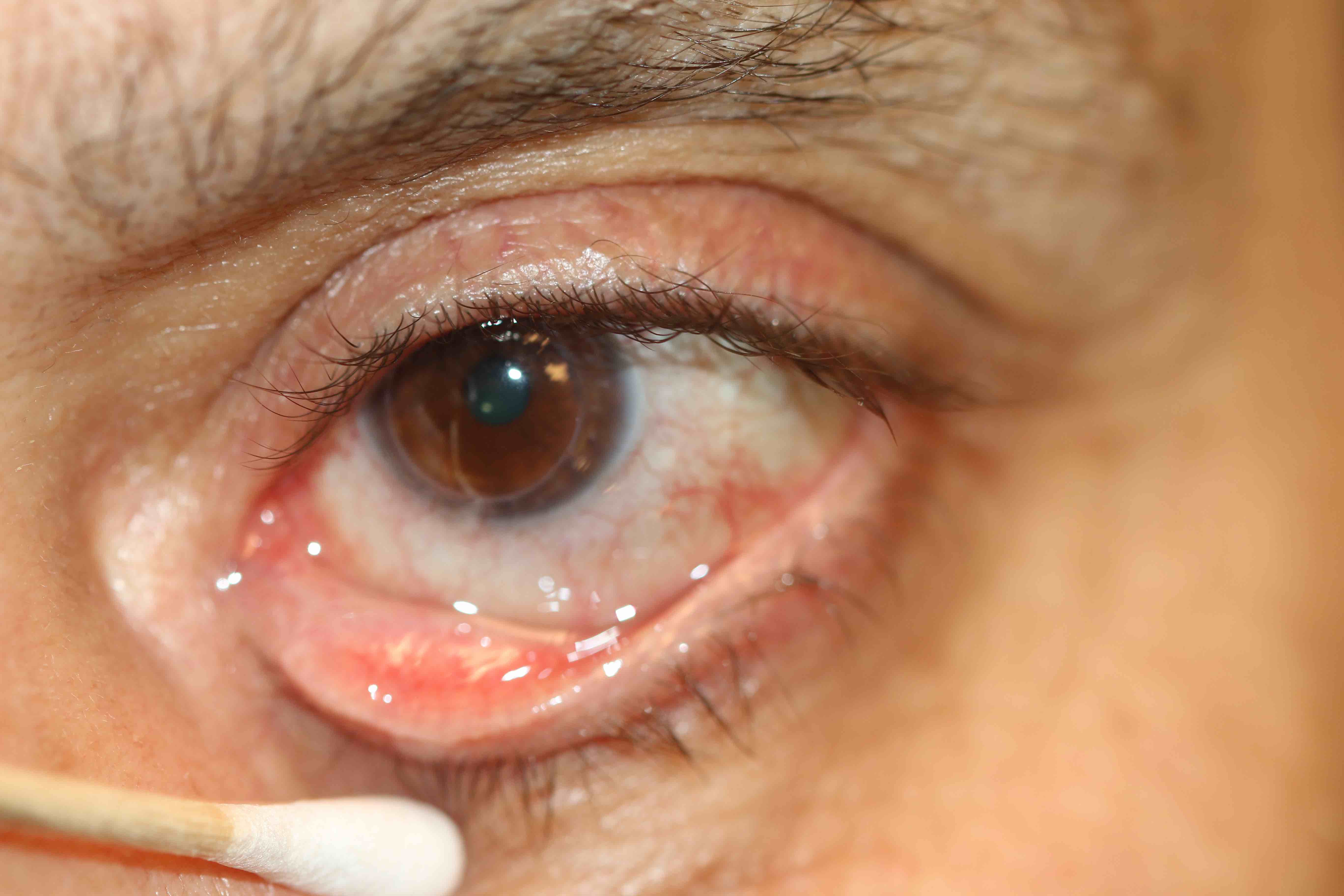

Patients usually present with symptoms of excessive lacrimation and ocular discomfort. Most commonly, punctal stenosis is associated with chronic inflammation. Symptoms will, therefore, include uncomfortable, red, watery eyes and tearing. The patient may present with mixed seborrheic and ulcerative blepharitis.[5]

The biomicroscopic examination takes into account the eyelid margin, punctal orifice, and the tear meniscus to classify punctal stenosis into four grades:[5]

- Grade 0 No punctum identified, punctal atresia or agenesis (Fig 1)

- Grade 1 Papilla covered with a membrane (exudative or true membrane) or fibrosis (Fig 2)

- Grade 2 Less than normal size but recognizable

- Grade 3 Normal (easily recognized)

- Grade 4 <2mm

- Grade 5 >2mm, larger than usual punctum

Probing and irrigation are performed to confirm the diagnosis. Obstruction in the canalicular system is defined as a soft resistance to probing. In order to assess the lower lacrimal system, irrigation is done with normal saline and an irrigating lacrimal cannula (23 G). A normal patent lacrimal system will have no reflux of normal saline, whereas any obstruction will be evident through regurgitation of normal saline through the punctum.

When assessing a patient for punctal stenosis, it is important to determine the resting position of the lower punctum in particular. It should not normally be visible to examination under the biomicroscope. The normal punctum sits, pointing backward in the medial tear lake. Early lower eyelid laxity and ectropion will only be detectable with examination under the biomicroscope when the lower punctum is seen to be pointing upwards or outwards, even if the lower eyelid position seems to be normal on examination. Uncorrected, these early medial ectropions will lead to progressive stenosis of the punctum.

Evaluation

The diagnosis is usually made on the basis of history, the dye disappearance test, and slit-lamp examination. Laboratory testing is generally not needed.

The fluorescein dye disappearance test is done prior to dilation. The tear meniscus is examined after 3 to 5 minutes of insertion of 2% fluorescein to check for the presence of the remaining dye. Usually, in punctal stenosis, there is a dye disappearance time of over 5 minutes.

Punctal dilation of the stenotic punctum with a Nettleship dilater is performed after the dilater is lubricated with ointment (Fig 5). Diagnostic canalicular probing and nasolacrimal duct irrigation are performed under topical anesthesia. A punctal finder is used to dilate the punctum, and a canalicular probe is inserted. A soft stop indicates canalicular obstruction, and a hard stop against the lacrimal bone indicates a patent canalicular system. Irrigation is performed with a 5ml normal saline syringe. In a normal system, there is the passage of free fluid into the nose or nasopharynx without reflux.

Fluorescein dye disappearance after dilation is then performed. The normal flow would show fluorescein disappearance in under 3 minutes.[13]

Treatment / Management

There are several treatment options available for punctal stenosis. The basic principle is to create a patent punctal opening and improve the drainage of tears whilst maintaining the function of the lacrimal pump. However, no gold standard treatment has yet been decided upon.

- Perforated punctal plug placement: The perforated plugs are placed following dilation and are left in place for 2 months. The underlying principle is that the longstanding dilation of the punctum occurs and prevents restenosis. The success rate for improvement of symptoms such as epiphora following the placement of perforated punctal plugs is 87% according to one study.[14] Failures were on account of restenosis or horizontal lid laxity. However, further trials are required to determine the long term success of the procedure.[14] (B2)

- Simple punctoplasty: Punctoplasty is a technique used to widen the punctal opening to enhance tear drainage. It involves dilatation of the punctum with increasing sizes of a dilator. This generally fails over time.

- One-snip punctoplasty: One-snip punctoplasty was a procedure developed to facilitate tear drainage by making a vertical incision along the canaliculus with a canaliculus knife, opening the posterior aspect of both the canaliculus and the punctum.[15] However, the procedure mostly failed secondary to wound reapproximation.

- Three-snip punctoplasty: Three-snip punctoplasty is a technique widely favored by general ophthalmologists and oculoplastic surgeons alike due to its success rates. It involves a vertical incision along the ampullae, horizontal incision along the canaliculus, and a final incision along the base of the free flap creating a triangular shape on the posterior part of the punctum and canaliculus.

- In one study, the primary three snip punctoplasty showed an 86% success rate with complete resolution of excessive lacrimation.[16] In another study, anatomical and functional success for punctoplasty was 91% and 64%, respectively.[17]

- One problem that arises as a result of the three snip punctoplasty is a poor functional outcome, due to distortion of the natural canalicular system, thereby causing persistent epiphora in some patients despite a patent lacrimal system.

- A solution proposed to solve this problem is the rectangular three snip punctoplasty, where vertical incisions are made on the medial and lateral borders of the vertical canaliculus. This modification of the traditional triangular three-snip to the rectangular three-snip punctoplasty helps to preserve the natural anatomy of the horizontal canaliculus and the punctum. Functional success has been shown to improve to 94%.[3]

(B2)

- Stent cannulation: Another intervention available is the mini-Monoka punctocanaliculoplasty. A mini monocanalicular stent is inserted after dilatation of the punctum. A study determined that 82% of eyes showed an improvement of symptoms following the procedure. This procedure is more effective for combined punctal and canalicular stenosis.[18] (B2)

- Wedge punctoplasty: A wedge-shaped removal of the punctum and vertical canaliculus has been used to treat punctal stenosis with promising results. This is a variation on the three-snip procedure. 95% of patients showed a patent punctum, and 92% of patients had symptomatic relief at follow-up.[19]

- Punch punctoplasty: This is similar to the wedge punctoplasty, where a punch like a glaucoma punch is used to remove a segment of the punctal border and vertical component of the canaliculus. Punch punctoplasty gave a 94% anatomical success rate and a 92% functional success rate.[20]

- Adjunct mitomycin C use after punctal dilatation or punctoplasty: Preoperative and postoperative topical mitomycin C has also been proven to be an effective adjunct therapy for punctal stenosis.[21] Mitomycin C is soaked onto the punctum before or after the procedure for three minutes. (B3)

- Balloon dilation: Balloon dilation rendered half the patients symptom-free according to one study. However, this technique is more suited to constriction of the nasolacrimal system in the nasolacrimal duct, usually in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The exact advantage in acquired punctal stenosis still remains to be elucidated.[22]

Differential Diagnosis

- Epiphora due to dry eye and reflex tearing

- Canalicular obstruction

- Nasolacrimal obstruction

- Congenital glaucoma

- Ectropion without punctal stenosis

Prognosis

In most patients, the prognosis is good. Recurrence of symptoms may occur after surgery in a minority of cases.

Complications

Two common problems associated with punctal stenosis are canalicular fibrosis (46%) and restenosis.[18] The rectangular three-snip punctoplasty technique effectively deals with restenosis. The mini-Monoka punctocanaliculoplasty (MMPC), preceded by punctal dilation, is a technique used to manage the problem of canalicular fibrosis.[18]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Since punctal stenosis presents with excessive lacrimation, in a wide number of patients, the increased tear film can cause impaired vision. Such patients are advised to get their visual acuity checked and abstain from driving after duly informing their relevant driving license authority.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Punctal stenosis is best managed by an interprofessional team with open communication, which involves general ophthalmologists, oculoplastic surgeons, laboratory technicians, nurses, pathologists, and pharmacists.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

A. Punctal stenosis caused by a chemical burn with conjunctival and lid margin muco-cutaneous junction scarring B. Complete obliteration of the puncta secondary to cicatrization caused by Stevens Johnson syndrome C. Punctal occlusion in the presence of mucous membrane pemphigoid disease Contributed by Professor Bhupendra C. K. Patel MD, FRCS

References

Bukhari A. Prevalence of punctal stenosis among ophthalmology patients. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Apr:16(2):85-7. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.53867. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20142967]

Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y, Iwaki M, Nakano T, Asamoto K, Ikeda H, Goto E, Selva D, Leibovitch I. Punctal and canalicular anatomy: implications for canalicular occlusion in severe dry eye. American journal of ophthalmology. 2012 Feb:153(2):229-237.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2011.07.010. Epub 2011 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 21982102]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCaesar RH, McNab AA. A brief history of punctoplasty: the 3-snip revisited. Eye (London, England). 2005 Jan:19(1):16-8 [PubMed PMID: 15184956]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHur MC, Jin SW, Roh MS, Jeong WJ, Ryu WY, Kwon YH, Ahn HB. Classification of Lacrimal Punctal Stenosis and Its Related Histopathological Feature in Patients with Epiphora. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2017 Oct:31(5):375-382. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2016.0129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28994268]

Kashkouli MB, Beigi B, Murthy R, Astbury N. Acquired external punctal stenosis: etiology and associated findings. American journal of ophthalmology. 2003 Dec:136(6):1079-84 [PubMed PMID: 14644218]

Tabbara KF, Bobb AA. Lacrimal system complications in trachoma. Ophthalmology. 1980 Apr:87(4):298-301 [PubMed PMID: 7393535]

Jager GV, Van Bijsterveld OP. Canalicular stenosis in the course of primary herpes simplex infection. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1997 Apr:81(4):332 [PubMed PMID: 9215069]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcNab AA. Lacrimal canalicular obstruction associated with topical ocular medication. Australian and New Zealand journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Aug:26(3):219-23 [PubMed PMID: 9717753]

Brink HM, Beex LV. Punctal and canalicular stenosis associated with systemic fluorouracil therapy. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Documenta ophthalmologica. Advances in ophthalmology. 1995:90(1):1-6 [PubMed PMID: 8549238]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCaravella LP Jr, Burns JA, Zangmeister M. Punctal-canalicular stenosis related to systemic fluorouracil therapy. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1981 Feb:99(2):284-6 [PubMed PMID: 7469866]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee V, Bentley CR, Olver JM. Sclerosing canaliculitis after 5-fluorouracil breast cancer chemotherapy. Eye (London, England). 1998:12 ( Pt 3a)():343-9 [PubMed PMID: 9775228]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePort AD, Chen YT, Lelli GJ Jr. Histopathologic changes in punctal stenosis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 May-Jun:29(3):201-4. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31828a92b0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23552606]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOzgur OR,Akcay L,Tutas N,Karadag O, Management of acquired punctal stenosis with perforated punctal plugs. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2015 Jul-Sep; [PubMed PMID: 26155080]

Konuk O, Urgancioglu B, Unal M. Long-term success rate of perforated punctal plugs in the management of acquired punctal stenosis. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008 Sep-Oct:24(5):399-402. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318185a9ca. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18806663]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJONES LT. The cure of epiphora due to canalicular disorders, trauma and surgical failures on the lacrimal passages. Transactions - American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. 1962 Jul-Aug:66():506-24 [PubMed PMID: 14452301]

Murdock J, Lee WW, Zatezalo CC, Ballin A. Three-Snip Punctoplasty Outcome Rates and Follow-Up Treatments. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2015 Jun:34(3):160-3. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2015.1014513. Epub 2015 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 25906237]

Shahid H, Sandhu A, Keenan T, Pearson A. Factors affecting outcome of punctoplasty surgery: a review of 205 cases. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Dec:92(12):1689-92. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.140681. Epub 2008 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 18786958]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHussain RN, Kanani H, McMullan T. Use of mini-monoka stents for punctal/canalicular stenosis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2012 May:96(5):671-3. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300670. Epub 2012 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 22241928]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEdelstein J, Reiss G. The wedge punctoplasty for treatment of punctal stenosis. Ophthalmic surgery. 1992 Dec:23(12):818-21 [PubMed PMID: 1494436]

Wong ES, Li EY, Yuen HK. Long-term outcomes of punch punctoplasty with Kelly punch and review of literature. Eye (London, England). 2017 Apr:31(4):560-565. doi: 10.1038/eye.2016.271. Epub 2016 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 27911445]

Lam S, Tessler HH. Mitomycin as adjunct therapy in correcting iatrogenic punctal stenosis. Ophthalmic surgery. 1993 Feb:24(2):123-4 [PubMed PMID: 8446348]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLachmund U, Ammann-Rauch D, Forrer A, Petralli C, Remonda L, Roeren T, Vonmoos F, Wilhelm K. Balloon catheter dilatation of common canaliculus stenoses. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2005 Sep:24(3):177-83 [PubMed PMID: 16169803]