Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Knee Medial Collateral Ligament

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Knee Medial Collateral Ligament

Introduction

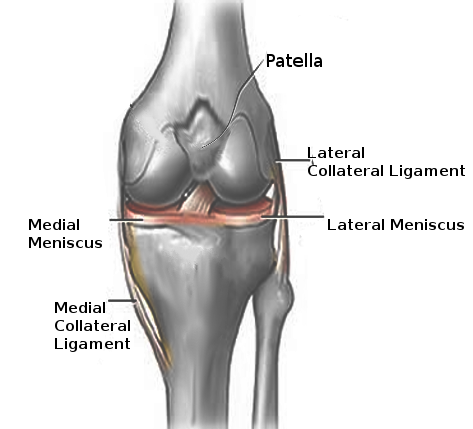

The tibial collateral ligament, also known as the medial collateral ligament (MCL), is a ligament extending from the medial epicondyle of the femur to the posteromedial crest of the tibia. The ligament is a broad and strong band that mainly functions to stabilize the knee joint in the coronal plane on the medial side.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The MCL is the primary passive and static stabilizer of the medial knee. It is composed of a superficial medial collateral ligament (sMCL) and a deep medial collateral ligament (dMCL). The sMCL has its proximal insertion at the medial epicondyle of the femur where it blends into the semimembranosus tendon. The distal attachment is at the posteromedial surface of the tibia. The dMCL is composed of 2 ligaments: meniscofemoral and meniscotibial. The meniscofemoral has its proximal insertion at the femur just distal to that of the sMCL; it attaches to the medial meniscus. The meniscotibial ligament is thicker and shorter. It travels from the medial meniscus to the distal edge of the articular cartilage of the medial tibial plateau.[3][4]

The superficial and deep ligaments each have a unique function, making the MCL the primary responder to valgus stress and a secondary restraint to rotational forces. The sMCL, specifically the proximal division, resists valgus forces through all degrees of knee flexion. The distal division of the sMCL helps stabilize external rotation of the knee at 30-degree flexion. The dMCL helps stabilize internal rotation of the knee from full extension through 90-degree flexion. Despite the relationship of the dMCL with the medial meniscus, there is no influence of the MCL on the stability of the medial meniscus.

Together, the MCL also helps guide the knee joint through its full range of motion when a tensile load is applied. With low load, the ligament is relatively compliant; with increasing load, the ligament responds with increasing stiffness until it is nearly linear. Beyond this, the MCL will continue to absorb energy until failure. The MCL also prevents hyperextension of the joint and posterior translation of the tibia, secondary to the function of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). The posterior oblique ligament, a continuum of oblique fibers at the posterior aspect of the MCL, is responsible for this function.

Finally, the ligament plays a role in joint position sense or proprioceptive feedback. When the MCL is stretched beyond its ability or exposed to an excessive load, it evokes neurological feedback signals that then generate a muscle contraction.

Embryology

By 9 weeks gestational age, the MCL begins to develop as a condensation of the joint capsule. A week earlier, in week 8, the fibular collateral ligament, or lateral collateral ligament (LCL), begins to develop independently of the knee capsule. The entire knee joint is fully developed by 14 weeks gestational age.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Branches of the superior and inferior genicular arteries supply the MCL. They enter through the epiligamentous (surface) layer; thus, the surface of the MCL is highly vascular. Its microvasculature branches into smaller neurovascular bundles deeper within the ligament, making deeper levels less vascular. No vessels cross bone, but they do enter the soft tissue of the ligament near the bony interfaces. Thus, the area near the bony insertions is more richly vascularized.

Nerves

The MCL is innervated by the medial articular nerve, a branch of the saphenous nerve. Innervation is greatest in the epiligament and near the insertions. The ligament can perceive pain and process proprioception through specialized sensory mechanoreceptors like Ruffini endings, Pacinian corpuscles, Golgi receptors, and bare nerve endings. Complete MCL tears will completely disrupt the pattern of innervation.

Muscles

While the MCL is the static stabilizer of the medial knee, the dynamic stabilizers of the medial knee are muscles: the semimembranosus complex, vastus medialis, and pes anserinus. The semimembranosus tightens the posterior oblique ligament and displaces the medial meniscus posteriorly to prevent impingement during knee flexion. The vastus medialis and pes anserinus potentially increase the stiffness of the MCL. However, the reaction time of these muscles is too slow to be protective against injury.

Surgical Considerations

Surgery is rarely indicated for MCL injuries.

In one subset of patients, MCL tears with tibial-sided avulsions or bony avulsions require acute surgical repair.

Surgery is also indicated in patients with chronic valgus instability refractory to rigorous conservative treatment if the injury affects activities of daily living or inability to participate in athletic events. The primary goal is to repair the MCL; however, in cases where scarring or incomplete healing make the torn edges difficult to identify, grafts are used to reconstruct the ligament. Allografts are either Achilles or tibialis anterior tendon, and autografts include the semitendinosus tendon.

Post-repair, the knee is braced in extension for 2 to 4 weeks to allow healing. Rehabilitation begins with motion exercises and progresses to strengthening exercises at 6 weeks. The brace is removed at 6 to 8 weeks. Post-MCL reconstruction follows the same rehabilitation progression as post-cruciate reconstruction with an emphasis on achieving full extension of the knee.

Clinical Significance

The MCL is one of the most commonly injured ligaments of the knee. Valgus stress is the most common mechanism of injury. Injuries can be contact (a direct blow to the outer aspect of the lower thigh or upper leg) or non-contact (common in skiing). Contact injuries are usually more severe. (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1888587/)

Patients with an MCL injury will present with pain (ranging from mild to severe), stiffness, swelling, tenderness of the medial knee, and knee instability.

Injuries are classified as grade I, II, or III based on the severity of damage and the laxity of the ligament, measured by medial joint opening with the valgus stress test (VST).

- Grade I: Involves a few fibers of the MCL with local tenderness and a solid endpoint; valgus opening less than 5 mm.

- Grade II: Disruption of more fibers with generalized tenderness and usually a firm or perceptible endpoint; valgus opening 5 to 9 mm.

- Grade III: Complete MCL tears with considerable tenderness and no perceptible endpoint; valgus opening greater than 10 mm. Grade III injury suggests that other knee ligaments may be injured.

Partial or complete ruptures in the ligament significantly increase the load on the ACL, putting the ACL at risk for a tear. The medial meniscus is often also injured due to its relationship with the dMCL.

Assessment

Assessment of the MCL is best within 20 to 30 minutes of injury before pain, swelling, and muscle spasms make examination difficult. The assessment includes palpation and a special test, the valgus stress test (VST). Moving vertically, midway along the medial joint line, the anterior aspect of the ligament can be palpated. Focal tenderness indicates an MCL injury. The VST assesses laxity of the MCL compared to the contralateral knee as a control. The test should be performed with the patient relaxed in a supine position and the knee in slight flexion to isolate the ligament. The examiner should place one hand on the lateral aspect of the knee joint line and the other hand on the medial ankle. Gentle valgus stress should be applied by manually moving the knee medially and the ankle laterally. A positive result would be an increase in medial joint space. Laxity at 30 degrees of flexion indicates injury to the sMCL while laxity at 0 degrees of flexion suggests injury to the dMCL.

When assessing for an MCL injury, the examiner should carefully inspect surrounding structures. Suspicion of additional injury may require imaging and referral to an orthopedic surgeon.

Treatment

Treatment is often non-operative because the MCL has strong vascular support for healing. Initial treatment includes:

- Rest, ice, compression, elevation (RICE) to control pain.

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen is commonly used for pain control and has no adverse effect upon healing.

- Protection from further injury: stop sports or heavy activity until full motion and strength is regained (usually within 3 to 6 weeks).

When rehabilitating an MCL injury, early joint motion is encouraged and weight-bearing as well as activity advance as tolerated by the patient. Rehabilitation is step-wise and like other musculoskeletal injuries. Patients must first restore active range of motion. Next, the goal is to improve strength, proprioception, agility, and general fitness. Athletes will go on to perform sports-specific activities and return to play.

Bracing is often recommended, though controversial. If a brace is used, usually for pain relief, a hinged knee brace is best to restrict medial movement but permit as much flexion as the patient can tolerate. Extension is often limited.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bourne M, Sinkler MA, Murphy PB. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Tibia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252309]

Gupton M, Imonugo O, Terreberry RR. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Knee. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763193]

Sprouse RA, McLaughlin AM, Harris GD. Braces and Splints for Common Musculoskeletal Conditions. American family physician. 2018 Nov 15:98(10):570-576 [PubMed PMID: 30365284]

Tadlock BA, Pierpoint LA, Covassin T, Caswell SV, Lincoln AE, Kerr ZY. Epidemiology of knee internal derangement injuries in United States high school girls' lacrosse, 2008/09-2016/17 academic years. Research in sports medicine (Print). 2019 Oct-Dec:27(4):497-508. doi: 10.1080/15438627.2018.1533471. Epub 2018 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 30318926]