Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Internal Iliac Arteries

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Internal Iliac Arteries

Introduction

The internal iliac artery (IIA), or hypogastric artery, is the primary artery supplying the pelvic viscera and an important contributor to structures of the pelvic wall, perineum, gluteal region, and thigh. The internal iliac artery arises where the common iliac artery bifurcates into internal and external iliac arteries; it then crosses the pelvic brim to give off numerous branches within the pelvis. The pelvic arteries arising from the internal iliac artery are highly variable in their branching pattern and number, an important feature to note during pelvic surgery. In addition, there are notable differences in the branches of the internal iliac artery in males and females, given that the reproductive organs are within their supply territory.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The internal iliac artery is one of two major arteries arising from the common iliac artery. The right and left common iliac arteries begin at approximately the level of the fourth or fifth lumbar vertebra (L4-L5), marking the terminal end of the abdominal aorta. Each common iliac artery bifurcates into an internal and external iliac artery, usually just anterior to the sacroiliac joint. The external iliac artery traverses along the pelvic brim to ultimately serve the lower extremity, while the more medially situated internal iliac artery crosses the pelvic brim to enter the lesser, or true, pelvis. The internal iliac artery descends posteromedially within the pelvic cavity and divides into anterior and posterior divisions, or trunks, near the superior margin of the greater sciatic foramen.[1]

Anterior Division

The anterior division of the internal iliac artery produces several branches that mostly supply visceral territories within the pelvis, but also parietal areas in the pelvis, gluteal region, and thigh. Despite considerable variation in these arteries, six branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery commonly exist. These branches include the umbilical artery, obturator artery, inferior vesical artery (in males), middle rectal artery, internal pudendal artery, and inferior gluteal artery.

One of the first branches of the anterior division, the umbilical artery, travels anteroinferior to cross the pelvic cavity lateral to the bladder. Post-birth, the umbilical artery is continuous with a non-patent fibrous cord called the medial umbilical ligament that continues to the deep surface of the lower anterior abdominal wall. In both sexes, the umbilical artery provides a branch to the superior surface of the bladder called the superior vesical artery. The umbilical artery also gives off the uterine artery serving the uterus in females. Subsequently, the uterine artery gives off the vaginal artery that serves as a major blood supply to the vagina. In males, the umbilical artery supplies the prostate and ductus deferens indirectly via the artery to the ductus deferens and prostatic branches that arise from the superior vesical artery.

The obturator artery is most often an early branch of the anterior division of the IIA but arises from the external iliac artery either directly or via the inferior epigastric artery in approximately 19% of individuals.[2] The obturator artery distributes branches to the iliacus and ilium within the pelvis. The obturator artery travels across the pelvis and through the obturator foramen to serve the femoral head and ultimately reach its main territory in the medial thigh.

Usually only present in males, the inferior vesical artery is the next branch of the anterior division that supplies the inferior aspect of the bladder. The inferior vesical artery has branches that serve the prostate and seminal vesicles, and sometimes the ductus deferens. The inferior vesical artery may share a common trunk with the middle rectal artery, or these arteries may arise from the anterior division of the IIA separately.

The middle rectal artery travels inferiorly from its origin to supply blood to a large segment of the middle and inferior rectum. It contributes to the rich arterial collateral circulation of the rectum, especially proximal to the pectinate line.

The internal pudendal artery and inferior gluteal artery are the terminal branches of the anterior division of the IIA. The internal pudendal artery exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen, curves past the closely situated ischial spine, and enters the perineum via the lesser sciatic foramen. Within the perineum, the internal pudendal artery travels with the internal pudendal vein and pudendal nerve through the pudendal, or Alcock, canal, which is located on the lateral wall of the pelvis and formed by the obturator membrane and muscle. Through its numerous branches, the internal pudendal artery serves as the primary blood supply to structures of the perineum.

After arising from the anterior division of the IIA, the inferior gluteal artery commonly descends along the superficial aspect of the piriformis to leave the pelvis and enter the gluteal region via the greater sciatic foramen. The inferior gluteal artery supplies blood to several muscles in the gluteal region, including the gluteus maximus, piriformis, obturator internus, superior and inferior gemellus, quadratus femoris, and proximal hamstrings.

Posterior Division

The posterior division of the internal iliac artery supplies parietal structures of the pelvis and gluteal region.[3] The branches of the posterior division are fewer in number than those of the anterior division and typically include the iliolumbar artery, lateral sacral arteries, and superior gluteal artery. The iliolumbar artery originates from the posterior division as a recurrent branch that quickly turns superolateral to serve the musculoskeletal structures of its namesake, the iliolumbar region. The iliolumbar artery often forms anastomoses with the superior gluteal artery and the circumflex iliac artery.[1]

The lateral sacral arteries are two branches of the posterior division that may arise from a common trunk or separately. These arteries, a superior and inferior lateral sacral artery, run inferomedially just anterior to the sacrum and piriformis and produce branches that supply the meninges and lower back muscles. The lateral sacral artery shares a collateral circulatory channel with the median sacral artery, a direct branch of the abdominal aorta.[1] The largest branch of the posterior division is the superior gluteal artery which exits the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen to serve muscles of the gluteal region. The superior gluteal artery has rich collateral circulation with the lateral sacral artery, internal pudendal arteries, and the inferior gluteal artery.[1]

Embryology

In adults, the internal and external iliac arteries bifurcate from the common iliac arteries at the fifth lumbar to the first sacral (L5-S1) vertebral level.[4] Given the differential growth of the aorta and its branches relative to the vertebral column, the vertebral level for the origin of the internal iliac artery shifts through development. The bifurcation level of the common iliac artery and origin of the inferior iliac artery is at the first sacral (S1) vertebral level during the first trimester. It is at the fifth lumbar (L5) vertebral level at birth.[4]

During fetal development, the internal iliac artery conveys oxygen-poor, nutrient-poor fetal blood to the placenta via the umbilical artery. The umbilical artery is within the umbilical cord and is a critical component of fetoplacental circulation. At birth, the portion of the umbilical artery that is extracorporeal contracts and is ultimately removed from neonatal circulation. Within the neonate, the proximal portion of the umbilical artery persists as the patent portion of the umbilical artery but the distal portion that communicated with the placenta contracts and becomes occluded. The non-patent remnant of the umbilical artery is evident as a fibrous cord called the medial umbilical ligament, which represents the path of the umbilical artery in utero.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The internal iliac artery (IIA) arises at the level of the sacroiliac joint, where the common iliac artery bifurcates into external and internal iliac branches. Branches of the internal iliac artery supply numerous structures of the pelvic wall, pelvic viscera, perineum, and gluteal region. Visceral branches of the internal iliac artery supply the urinary bladder, rectum, and urethra in both sexes. In males, the visceral branches of the IIA also serve the prostate, ductus deferens, seminal vesicles, ejaculatory ducts, whereas, in females, they serve the uterus and vagina.[6] Parietal branches of the internal iliac artery supply a variety of musculoskeletal structures located within the thigh, hip joint, and gluteal region.[6]

Lymphatic channels run along branches of the internal iliac vessels to the internal iliac, or hypogastric, lymph nodes. These lymph nodes are nestled on and around branches of the internal iliac artery and receive lymphatic fluid from pelvic portions of the digestive tract, urinary organs, and reproductive organs. Afferent lymph vessels convey lymphatic fluid towards the internal iliac nodes, and efferent lymph vessels convey lymphatic fluid to lymphatic collectors located superior to the nodes, primarily the common iliac lymph nodes.[7]

Physiologic Variants

The internal iliac artery and its branches display significant variation in branching patterns, location, and areas supplied. The internal iliac artery itself varies with regard to the level of its origin and where it branches into anterior and posterior divisions. Some of the more common arterial variants arising from the anterior and posterior divisions of the IIA are summarized in the following paragraphs.

Typically one of the first branches of the anterior division of the internal iliac artery, the obturator artery, can arise from the posterior division or other branches of the anterior division such as the inferior epigastric artery or inferior vesical artery. Infrequently, an anatomic variant referred to as an aberrant or accessory obturator artery is present. The aberrant obturator artery arises from the external iliac artery, and it may do so instead of or in addition to an obturator artery arising from the IIA Arterial variants that contribute to a collateral path between the internal and external iliac arteries are referred to as corona mortis or the crown of death.[8] One such variant presents as an anastomotic branch between the inferior epigastric artery and obturator artery in the obturator canal, while another form involves an aberrant obturator artery arising from the external iliac artery and forming an anastomotic connection with the obturator artery that arises from the internal iliac artery.[8]

In females, the vaginal artery is most often a branch of the umbilical artery, but it may also arise directly from the anterior division of the IIA. In addition, the inferior vesical artery is sometimes present in females as a small branch of the uterine artery or vaginal artery.

In males, the inferior vesical artery may share a common trunk with the middle rectal artery. In addition, the artery to the ductus deferens may arise from either the superior vesical artery or the inferior vesical artery.

In both sexes, the internal pudendal artery and the middle rectal artery sometimes arise from a common trunk. An accessory internal pudendal artery is variably present, arising from another pelvic artery such as the inferior vesical artery, obturator artery, or external iliac artery.

The posterior division's iliolumbar artery may arise directly from the trunk of the internal iliac artery proximal to its bifurcation into anterior and posterior divisions.[3] Finally, the branches of the internal iliac artery participate in highly variable, rich collateral circulatory routes in the pelvis, thigh, and gluteal region.

Surgical Considerations

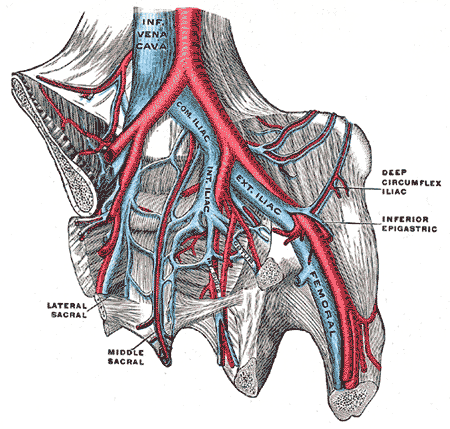

Knowledge of the internal iliac artery and its branches is of critical importance in a variety of pelvic procedures due to the IIA's primary role in blood supply to the pelvic viscera and its potential for ligation or compression at times of massive pelvic hemorrhage. Moreover, the surgeon should be very familiar with how the internal iliac artery is closely situated to a number of musculoskeletal and neurovascular structures within the pelvis, including the ureter, anteriorly; the internal iliac vein, posteromedially; the external iliac vein, obturator nerve, and obturator vein, posterolaterally; the ileum and cecum, anteromedially on the right; and the psoas major and internal obturator muscles, laterally.[9] See Image. Pelvic Veins.

In acute situations involving the pelvic region, knowledge of the level of the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and the level of division of the internal iliac artery is of paramount importance. Unilateral or bilateral ligation of the internal iliac artery can be lifesaving for patients experiencing such conditions as massive pelvic hemorrhage, hemorrhage after a vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy, massive broad ligament hematoma, cervical carcinoma, peripartum bleeding, intraperitoneal bleeding of indeterminate origin, and retroperitoneal bleeding following a pelvic fracture.[3][10][11][12][13] It is preferable to ligate the internal iliac artery distal to the posterior division's origin as there is evidence that proximal ligation of the internal iliac artery can result in claudication and necrosis in the gluteal region.[3][14][15] When trying to control a massive pelvic hemorrhage or postpartum bleed, bilateral ligation of the internal iliac arteries will reduce blood flow in the pelvic arteries by approximately 50% and pulse pressure by 85%, which supports coagulation and hemostasis.[16] Bilateral ligation of the internal iliac arteries is a lifesaving but controversial treatment for women experiencing massive obstetric hemorrhage. However, in contrast to an emergency hysterectomy, bilateral ligation of the internal iliac arteries typically preserves female fertility.[17]

Following long-term bilateral ligation of the internal iliac artery, collateral circulation largely supplied by the deep femoral artery will contribute to the revascularization of the internal iliac artery. This process is primarily achieved via anastomoses of the superior gluteal artery with the lateral femoral circumflex artery and the obturator artery with the medial femoral circumflex artery.[18]

It is critical to be mindful of the ureter during pelvic surgeries involving the internal iliac artery and its branches, particularly given the close proximity of the ureter to the bifurcation of the common iliac artery into external and internal iliac arteries. The ureter crosses into the pelvis around the bifurcation of the common iliac artery and runs along the medial aspect of the internal iliac artery. During a hysterectomy, surgeons must be careful when ligating the uterine artery, given that the ureter crosses deep to it and is at risk of injury at this site.[1] The anatomic course of the ureter is also vital knowledge as it is at risk of damage during emergency internal iliac artery ligation to control hemorrhage. The ureter usually rests on the anterior surface of the internal iliac artery and must be identified before ligation is completed.[3]

Knowledge of the branches of the internal iliac artery is critical in a variety of pelvic procedures. For instance, the aberrant obturator artery traverses over the superior pubic ramus, where it is at risk of injury from pubic fracture or inguinal hernia repair.[8] Laceration of the internal pudendal artery can be managed by compression of the ischioanal, or ischiorectal, fossa.[1] Additionally, the inferior gluteal artery is at risk of injury during sacrospinous ligament fixation surgeries[1].

Careful consideration of the many anatomic variants of the internal iliac artery is important in reducing a variety of potential surgical complications. As an example, it is important to note in individuals with corona mortis that compression of the internal iliac artery will not completely stop bleeding from its contributing arteries since the external iliac artery also supplies this vascular loop. However, compression of the internal iliac artery will control the blood flow contributed by the IIA to the corona mortis.[19]

Clinical Significance

The internal iliac artery conveys a relatively large volume of blood, and its branches supply numerous visceral and parietal structures in the pelvis, gluteal region, hip, and thigh. As a result, blunt force trauma, penetrating injuries, and pelvic fractures put these vessels at considerable risk with potentially life-threatening consequences.

The internal iliac arteries are at risk of various pathologies that impact the arterial system. Internal iliac artery stenosis is a relatively common occurrence that is often due to atherosclerosis. This condition is typically associated with aortic or common iliac artery stenosis.[20] Isolated occlusion of the internal iliac arteries may occur, although it is less common and more challenging to diagnose than aortoiliac-associated disease.[21] The rich collateral circulation of the branches of the internal iliac artery hep to bypass arterial obstructions resulting from surgery, trauma, or arterial disease.

Frequently associated with atherosclerosis, isolated internal iliac artery aneurysms are relatively uncommon. They occur in only 20% of individuals presenting with isolated aneurysms of either the common iliac, external iliac, or internal iliac artery.[22]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pelvic Veins. Pelvic veins include the inferior vena cava, internal iliac vein, common iliac vein, external iliac vein, femoral vein, deep circumflex iliac vein, middle sacral vein, and lateral sacral vein.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Selçuk İ, Yassa M, Tatar İ, Huri E. Anatomic structure of the internal iliac artery and its educative dissection for peripartum and pelvic hemorrhage. Turkish journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Jun:15(2):126-129. doi: 10.4274/tjod.23245. Epub 2018 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 29971190]

Pai MM, Krishnamurthy A, Prabhu LV, Pai MV, Kumar SA, Hadimani GA. Variability in the origin of the obturator artery. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2009:64(9):897-901. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322009000900011. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19759884]

Mamatha H, Hemalatha B, Vinodini P, Souza AS, Suhani S. Anatomical Study on the Variations in the Branching Pattern of Internal Iliac Artery. The Indian journal of surgery. 2015 Dec:77(Suppl 2):248-52. doi: 10.1007/s12262-012-0785-0. Epub 2012 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 26730003]

Ozgüner G,Sulak O, Development of the abdominal aorta and iliac arteries during the fetal period: a morphometric study. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2011 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 20623285]

Tokar B, Yucel F. Anatomical variations of medial umbilical ligament: clinical significance in laparoscopic exploration of children. Pediatric surgery international. 2009 Dec:25(12):1077-80. doi: 10.1007/s00383-009-2467-y. Epub 2009 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 19727772]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFătu C, Puişoru M, Fătu IC. Morphometry of the internal iliac artery in different ethnic groups. Annals of anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger : official organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft. 2006 Nov:188(6):541-6 [PubMed PMID: 17140147]

Wolfram-Gabel R. [Anatomy of the pelvic lymphatic system]. Cancer radiotherapie : journal de la Societe francaise de radiotherapie oncologique. 2013 Oct:17(5-6):549-52. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2013.05.010. Epub 2013 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 24007954]

Al Talalwah W, A new concept and classification of corona mortis and its clinical significance. Chinese journal of traumatology = Zhonghua chuang shang za zhi. 2016 Oct 1; [PubMed PMID: 27780502]

Shrestha R, Shrestha S, Sitaula S, Basnet P. Anatomy of Internal Iliac Artery and Its Ligation to Control Pelvic Hemorrhage. JNMA; journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2020 Oct 15:58(230):826-830. doi: 10.31729/jnma.4958. Epub 2020 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 34504379]

Camuzcuoglu H, Toy H, Vural M, Yildiz F, Aydin H. Internal iliac artery ligation for severe postpartum hemorrhage and severe hemorrhage after postpartum hysterectomy. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research. 2010 Jun:36(3):538-43. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01198.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20598034]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEvans S, McShane P. The efficacy of internal iliac artery ligation in obstetric hemorrhage. Surgery, gynecology & obstetrics. 1985 Mar:160(3):250-3 [PubMed PMID: 3871975]

Tomacruz RS, Bristow RE, Montz FJ. Management of pelvic hemorrhage. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2001 Aug:81(4):925-48 [PubMed PMID: 11551134]

Sanders AP, Hobson SR, Kobylianskii A, Papillon Smith J, Allen L, Windrim R, Kingdom J, Murji A. Internal iliac artery ligation-a contemporary simplified approach. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2021 Sep:225(3):339-340. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.05.003. Epub 2021 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 34097908]

Bleich AT, Rahn DD, Wieslander CK, Wai CY, Roshanravan SM, Corton MM. Posterior division of the internal iliac artery: Anatomic variations and clinical applications. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007 Dec:197(6):658.e1-5 [PubMed PMID: 18060970]

Iliopoulos JI,Howanitz PE,Pierce GE,Kueshkerian SM,Thomas JH,Hermreck AS, The critical hypogastric circulation. American journal of surgery. 1987 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 3425815]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBurchell RC. Physiology of internal iliac artery ligation. The Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology of the British Commonwealth. 1968 Jun:75(6):642-51 [PubMed PMID: 5659060]

Wagaarachchi PT, Fernando L. Fertility following ligation of internal iliac arteries for life-threatening obstetric haemorrhage: case report. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2000 Jun:15(6):1311-3 [PubMed PMID: 10831561]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAkinwande O, Ahmad A, Ahmad S, Coldwell D. Review of pelvic collateral pathways in aorto-iliac occlusive disease: demonstration by CT angiography. Acta radiologica (Stockholm, Sweden : 1987). 2015 Apr:56(4):419-27. doi: 10.1177/0284185114528172. Epub 2014 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 24622738]

Karkare N,Yeasting RA,Ebraheim NA,Espinosa N,Scheyerer MJ,Werner CM, Anatomical considerations of the internal iliac artery in association with the ilioinguinal approach for anterior acetabular fracture fixation. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2011 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 20585791]

Mahé G, Kaladji A, Le Faucheur A, Jaquinandi V. Internal Iliac Artery Stenosis: Diagnosis and How to Manage it in 2015. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine. 2015:2():33. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2015.00033. Epub 2015 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 26664904]

Brewer MB, Lau DL, Lee JT. Endovascular Treatment of Claudication due to Isolated Internal Iliac Artery Occlusive Disease. Annals of vascular surgery. 2019 May:57():48.e1-48.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.07.034. Epub 2018 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 30114502]

Krupski WC, Selzman CH, Floridia R, Strecker PK, Nehler MR, Whitehill TA. Contemporary management of isolated iliac aneurysms. Journal of vascular surgery. 1998 Jul:28(1):1-11; discussion 11-3 [PubMed PMID: 9685125]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence