Introduction

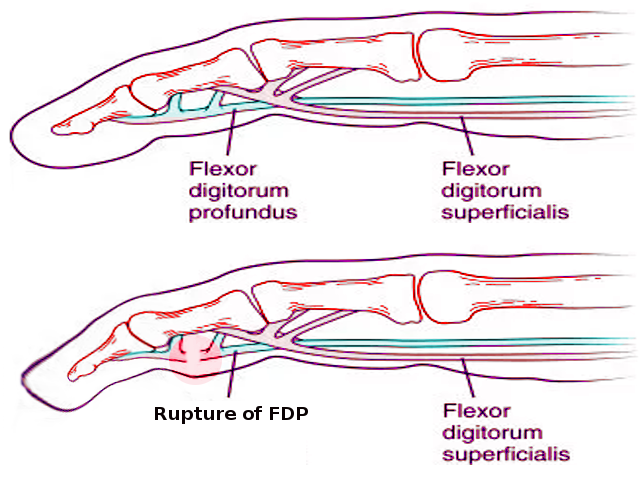

Jersey finger (also known as rugby finger) is an avulsion of the flexor digitorium profundus tendon (FDP) from its distal insertion on the distal phalanx (zone I).[1][2][3] The mechanism of injury is typically a forced extension of a flexed digit, such as trying to grab the jersey of an opponent during a high-speed sporting event. On exam, the affected digit remains in slight extension compared to the other digits. No active flexion of the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP) is possible. Treatment is surgical with the treatment plan dictated by the acuity of injury, the zone of injury, and any associated fracture.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The distal phalanx suffers exposure to substantial forces during pull-away mechanisms. Flexor digitorium distal avulsion commonly presents in young athletes, especially in contact sports.[4] The mechanism of injury typically results from forceful extension of a flexed digit. A common example is grabbing the jersey of an opposing player to make a tackle during American football or rugby, resulting in a forced extension of the flexor digitorium profundus tendon during maximum contraction of the muscle belly.

Epidemiology

Finger injuries account for 38% of all acute upper extremity injuries.[5] A recent study showed that tendon injuries in the hand occur at a rate of 33.2 per 100000 person-years. Only 4% of these injuries occur in flexor tendon zone I (distal to the insertion of flexor digitorum superficialis on the middle phalanx).[6]

Jersey finger can happen in any digit and represents the most common closed flexor tendon injury.[7] The ring finger is the most common involved digit (75% of the cases). When performing gripping, the ring fingertip becomes the most prominent digit in the vast majority of the population. Also, the ring finger is bound on both sides by lumbrical muscles, making it more prone to hyperextension injuries. There are reports that the load to failure of the FDP tendon needed for the ring finger is much less than other digits.[8]

Pathophysiology

DIP joint hyperextension during maximal FDP muscle belly contraction (clenched fist) leads to failure. The injury occurs to the distal tendon insertion at the base of the phalanx as this area represents its weakest point.[9]

History and Physical

It is crucial to have a high level of suspicion for a jersey finger in athletes with finger pain and to associate these injuries to sport-related trauma. Pain and tenderness of the volar aspect of the injured finger are the common presentations. In a resting position, the injured finger will usually remain in extension compared to the other digits. Sometimes, the retracted tendon can be palpated proximally to the avulsion. Flexion of the DIP joint is absent. Grip and flexion against resistance will usually cause pain.

Evaluation

Although physical examination should be enough to reach the diagnosis of jersey finger, X-rays and ultrasound may play an important role. Plain radiographs are mandatory to rule out fractures. Antero-posterior and lateral views may reveal a bony fragment, if present. Ultrasound may be useful to asses tendon anatomy in cases without fracture. In chronic injuries, ultrasound becomes crucial to evaluate tendon retraction and guide further treatment.

MRI is rarely performed but can be used to determine the increased tendon-bone distance more accurately.[10]

Treatment / Management

The typical treatment for jersey finger injuries is surgery. Early treatment is essential to restore blood supply and function. Flexor tendons nourish themselves from blood vessels located inside the mesotendon (long and short vincula). Conservative treatment has been minimal reporting in cases of high-risk surgical patients.[11][12](B3)

Surgical Management

- Acute: within 3 weeks after injury.

- Without fracture: direct tendon repair or tendon reinsertion (mini-suture anchor).

- Fracture fragment: calls for open reduction and internal fixation (mini-screws, wires). Currently, suture anchors are being used in cases of bony avulsions as well.

There are multiple, described proven treatment techniques for acute injuries. None of these seem to be significantly superior to the others.[13]

- Chronic: over 3 months after injury.

- Two-stage tendon grafting (if the full range of motion is present).

- DIP joint arthrodesis (if chronic stiffness is present). Joint arthrodesis requires careful discussion with each patient. The distal interphalangeal joint motion may be essential for some patients (occupation and hobbies), and tendon reconstruction may become a valid alternative. Unfortunately, tendon reconstruction requires a significant time commitment from the patient to achieve a successful long-term rehabilitation outcome.

Differential Diagnosis

Jersey finger injuries may get dismissed as minor sprains or phalanx fractures. There are several reports of athletes “playing through” the injury, even at a competitive level.[3]

Treatment Planning

The surgical approach in the presence of a bony avulsion is challenging. Preoperative planning should consider fragment size, fragment displacement, and soft tissue repair.[14]

Treatment of a jersey finger should take into account each patient’s goals and expectations. Treatment in sport-related injuries may be influenced by the athlete’s playing position and the level of competition.

Staging

Jersey Finger Injury Classification[9]

- Type 1: Severe avulsion. The tendon retracts into the palm. Blood supply is severely compromised.

- Type 2: The tendon retracts but remains at the A3 pulley (proximal interphalangeal joint).

- Type 3: The avulsion includes a bony fragment. Both tendon and fracture fragment remain at the A4 pulley.

- Type 4: Rare injury, defined by the presence of both a fracture and a tendon avulsion from the bony fragment. The tendon can retract into the palm.

Prognosis

Early diagnosis leads to expedited treatment with excellent functional outcomes. Surgery within 10 days after the injury correlates with excellent patient-reported outcomes.[15]

Patients may return to sports with both full active functional range of motion and the absence of pain (approximately 8 to 12 weeks).

Functional consequences of impaired DIP joint motion includes loss of dexterity and loss of pinch strength.[3]

Postoperative functional and aesthetic results depend on accurate reduction, repair quality, and an adequate rehabilitation protocol. Prevention of scar contracture formation is crucial to maintain finger function.[16][17]

Complications

A tendon advancement of over 1 cm carries the risk of quadriga. The term quadriga refers to an inability to flex the digits adjacent to the involved digit from increased tension over the repaired tendon.[18]

Other surgical complications include infection, skin necrosis, tendon repair rupture, nail matrix injury, and adhesions.[19][20]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The amount of force and tendon excursion applied in postoperative occupational therapy is one of the most important aspects of jersey finger management. Wound characteristics and patient compliance require strong consideration. Excessive forces can lead to tendon re-rupture. Proper wrist, digit, and metacarpophalangeal positions play an important role in controlling rehabilitation forces.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be aware of chronic pain and the loss of grip strength as consequences of delayed management of jersey finger injuries. Although the nonunion rate in bony-avulsion type jersey finger injuries is low, smoking cessation is a recommendation for fracture healing.

Pearls and Other Issues

Surgical Tips Include

-

Final circumferential suture improves final repair strengh.

-

Tendon retrieval should take place by performing incisions in low-risk areas.

- Accurate tendon orientation is crucial.

-

Tendon handling should be minimal.

-

Sheath closure is not necessary and only performed if it improves tendon gliding.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Physical examination is the key to reach a proper diagnosis. General practitioners, including nurse practitioners and physician assistants (PAs), should be aware that early diagnosis will lead to expedient treatment with superior outcomes. Most patients initially present to the primary caregiver, emergency department, or nurse practitioner and hence, knowledge of a jersey finger is necessary to avoid the morbidity. Prompt referral to an orthopedic hand surgeon is almost always essential for definitive management.

Orthopedic surgeons must provide information regarding physical examination and complications of delayed diagnosis to other healthcare providers. Patients should always receive counsel regarding treatment options, especially those involved in sports.

Nursing should assist in the management process by helping during evaluation and surgery in the event a surgical treatment route is chosen, as well as assessing patient progress and compliance on subsequent visits. Pharmacists play only a minor role in this condition, primarily consisting of post-operative pain medication consult, with a view towards avoiding opioids if possible; they can consult with the provider on other pain management options outside of opioids.

Physical or occupational therapists can be crucial in both surgical recovery and non-surgical management and should coordinate with the treating physician on progress, since irrespective of the chosen treatment course, patients do need rehabilitation to restore finger function and joint mobility. The physical therapist should report on progress to the surgeon. Only through open communication between all members of the interprofessional healthcare team can the morbidity of a jersey finger be avoided. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Lunn PG, Lamb DW. "Rugby finger"--avulsion of profundus of ring finger. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1984 Feb:9(1):69-71 [PubMed PMID: 6707505]

Folmar RC, Nelson CL, Phalen GS. Ruptures of the flexor tendons in hands of non-rheumatoid patients. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1972 Apr:54(3):579-84 [PubMed PMID: 5055155]

Bachoura A, Ferikes AJ, Lubahn JD. A review of mallet finger and jersey finger injuries in the athlete. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2017 Mar:10(1):1-9. doi: 10.1007/s12178-017-9395-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28188545]

Yeh PC, Shin SS. Tendon ruptures: mallet, flexor digitorum profundus. Hand clinics. 2012 Aug:28(3):425-30, xi. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.05.040. Epub 2012 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 22883898]

Ootes D, Lambers KT, Ring DC. The epidemiology of upper extremity injuries presenting to the emergency department in the United States. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2012 Mar:7(1):18-22. doi: 10.1007/s11552-011-9383-z. Epub 2011 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 23449400]

de Jong JP, Nguyen JT, Sonnema AJ, Nguyen EC, Amadio PC, Moran SL. The incidence of acute traumatic tendon injuries in the hand and wrist: a 10-year population-based study. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2014 Jun:6(2):196-202. doi: 10.4055/cios.2014.6.2.196. Epub 2014 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 24900902]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBOYES JH, WILSON JN, SMITH JW. Flexor-tendon ruptures in the forearm and hand. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1960 Jun:42-A():637-46 [PubMed PMID: 13849148]

Manske PR, Lesker PA. Avulsion of the ring finger flexor digitorum profundus tendon: an experimental study. The Hand. 1978 Feb:10(1):52-5 [PubMed PMID: 710982]

Leddy JP, Packer JW. Avulsion of the profundus tendon insertion in athletes. The Journal of hand surgery. 1977 Jan:2(1):66-9 [PubMed PMID: 839056]

Klauser A, Frauscher F, Bodner G, Halpern EJ, Schocke MF, Springer P, Gabl M, Judmaier W, zur Nedden D. Finger pulley injuries in extreme rock climbers: depiction with dynamic US. Radiology. 2002 Mar:222(3):755-61 [PubMed PMID: 11867797]

Zemirline A, Asmar G, Liverneaux PA. Conservative treatment in Jersey finger: a case report. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2013 Nov:66(11):1616-8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.03.026. Epub 2013 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 23602271]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePappas N, Gay AN, Major N, Bozentka D. Case report: pseudotendon formation after a type III flexor digitorum profundus avulsion. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Aug:469(8):2385-8. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1906-y. Epub 2011 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 21538197]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePolfer EM, Sabino JM, Katz RD. Zone I Flexor Digitorum Profundus Repair: A Surgical Technique. The Journal of hand surgery. 2019 Feb:44(2):164.e1-164.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.08.015. Epub 2018 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 30309664]

Halát G, Negrin LL, Unger E, Koch T, Streicher J, Erhart J, Platzer P, Hajdu S. Introduction of a new repair technique in bony avulsion of the FDP tendon: A biomechanical study. Scientific reports. 2018 Jul 2:8(1):9906. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28250-y. Epub 2018 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 29967345]

Tuttle HG, Olvey SP, Stern PJ. Tendon avulsion injuries of the distal phalanx. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2006 Apr:445():157-68 [PubMed PMID: 16601414]

Becker H. Primary repair of flexor tendons in the hand without immobilisation-preliminary report. The Hand. 1978 Feb:10(1):37-47 [PubMed PMID: 101426]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBecker H, Orak F, Duponselle E. Early active motion following a beveled technique of flexor tendon repair: report on fifty cases. The Journal of hand surgery. 1979 Sep:4(5):454-60 [PubMed PMID: 387859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGillig JD, Smith MD, Hutton WC, Jarrett CD. The effect of flexor digitorum profundus tendon shortening on jersey finger surgical repair: a cadaveric biomechanical study. The Journal of hand surgery, European volume. 2015 Sep:40(7):729-34. doi: 10.1177/1753193415585311. Epub 2015 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 25969412]

McCallister WV, Ambrose HC, Katolik LI, Trumble TE. Comparison of pullout button versus suture anchor for zone I flexor tendon repair. The Journal of hand surgery. 2006 Feb:31(2):246-51 [PubMed PMID: 16473686]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceZook EG. Complications of the perionychium. Hand clinics. 1986 May:2(2):407-27 [PubMed PMID: 3700492]