Introduction

The nasopalatine nerve, also known as nervus incisivus, is a division of the trigeminal nerve's maxillary branch.[1] The nasopalatine nerve branches off the maxillary nerve at the pterygopalatine fossa and passes through the sphenopalatine foramen to enter the nasal cavity. The nerve descends diagonally and anteriorly before emerging in the anterior palate via the incisive foramen. The nasopalatine nerve generally carries sensory information from the mucosal surfaces of the palatine and nasal septal regions.

Clinically, a block to the nasopalatine nerve facilitates anesthetizing the palatal mucosa and gingivae surrounding the 6 anterior maxillary teeth. Nasopalatine nerve blocks allow procedures involving the premaxilla, such as elevating mucosal flaps for oral and maxillofacial surgery and repairing cleft defects. Understanding this nerve's anatomy and function is essential to managing various orofacial conditions.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The nasopalatine nerve is a branch of the maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve (5th cranial nerve or CN V). The trigeminal nerve is a mixed sensorimotor nerve that exits the brain from the lateral surface of the pontine body as 2 roots, one large with sensory functions and the other small with motor impulses. Both roots travel from the pons to the middle cranial fossa floor to reach the trigeminal ganglion in a temporal bone depression known as the Meckel cave. Sensory root fibers synapse with the ganglion and give rise to the trigeminal nerve's 3 main sensory divisions: the ophthalmic and maxillary nerves and the sensory portion of the mandibular division. Unlike its sensory counterpart, the trigeminal nerve's motor root bypasses the trigeminal ganglion without synapsing and joins the mandibular branch's sensory root at the foramen ovale.

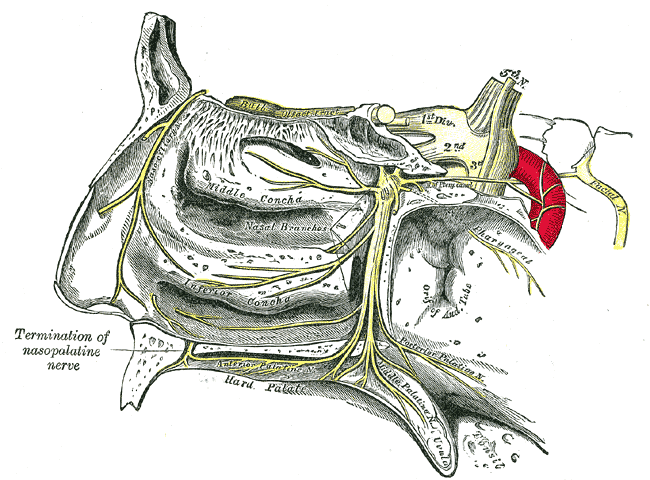

The maxillary division of the trigeminal nerve is sensory in function. This nerve leaves the cranium via the foramen rotundum and enters the pterygopalatine fossa. The pterygopalatine fossa is a cone-shaped space posterior to the maxilla, bounded by the maxillary, sphenoid, and palatine bones. The fossa contains many important anatomical structures, including the maxillary nerve and arteries and the pterygopalatine ganglion. The maxillary nerve divides into its branches at the pterygopalatine fossa. Some branches emerge from the maxillary nerve only after synapsing with the pterygopalatine ganglion. Other branches diverge directly from the main root of the maxillary nerve. The nasopalatine nerve emerges from the pterygopalatine ganglion (see Image. Trigeminal Nerve, Nasopalatine Distribution).

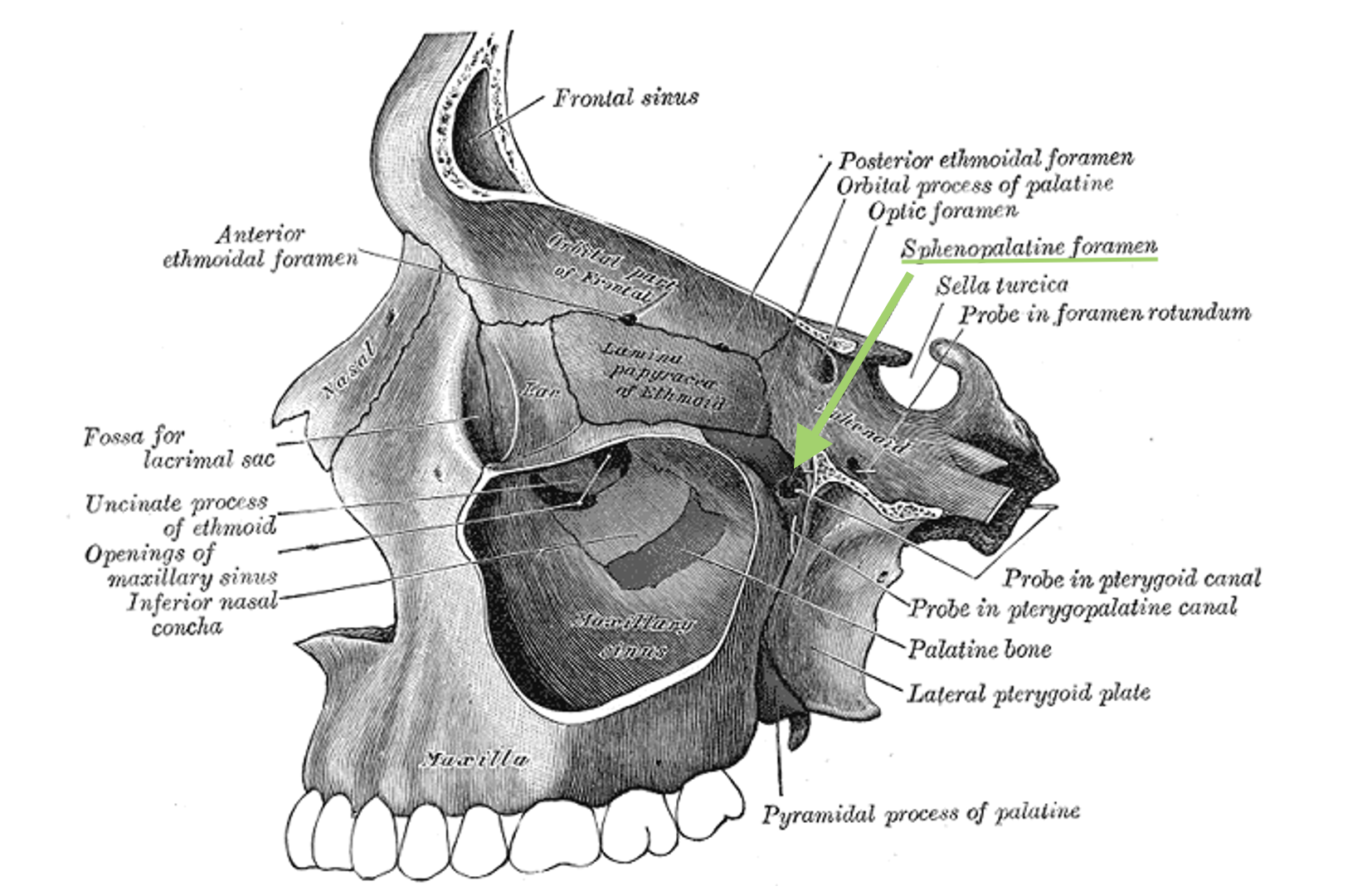

The nasopalatine nerve is the largest of the pterygopalatine ganglion's branches. This nerve enters the nasal cavity via the sphenopalatine foramen (see Image. Sphenopalatine Foramen). This foramen forms from the articulation of the palatine and sphenoid bones in the lateral nasal wall.[2]

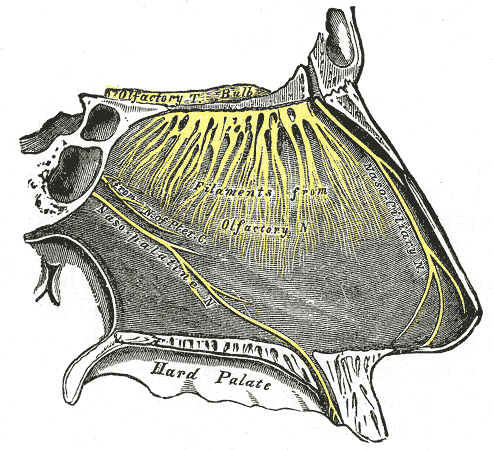

Once in the nasal cavity, the nasopalatine nerve passes inferior to the sphenoid sinus ostium to reach the nasal septum. The nerve then courses between the periosteum and the nasal septum's mucous membrane, providing sensation to the mucosa of this region. From here, the nasopalatine nerve travels anteriorly and inferiorly to pierce the hard palate anteriorly through the nasopalatine canal, which links the nasal and oral cavities (see Image. Nasopalatine Region Innervation). Other structures in the nasopalatine canal include the terminal branch of the nasopalatine artery, a small amount of fatty tissue, and the palatine glands.

The right and left nasopalatine nerves anastomose before emerging into the oral cavity through the incisive foramen.[3] The incisive foramen is an opening in the anterior maxilla just behind the central incisors. The nasopalatine nerve communicates with both greater palatine nerves after exiting the incisive foramen.[4] Together, these nerves provide general sensory innervation to the hard palate.

The nasopalatine nerve supplies general sensory innervation to the palate's anterior region. The nerve also provides innervation to the maxillary incisors in some individuals.[5] A nasopalatine nerve block anesthetizes the palatal tissues of the 6 maxillary anterior teeth. The greater palatine nerve provides general sensory innervation to the soft tissues of the palate from the canines onward. However, these 2 nerves have overlapping distributions.[6][7] The greater palatine nerve seems to adopt a more significant role in innervating the anterior palate than the nasopalatine nerve during childhood.[8]

Embryology

The trigeminal nerve and its branches originate from the 1st pharyngeal arch, which develops in the 3rd to 4th week of gestation.[9] The nasopalatine canal forms as part of the primary palate, created by the fusion of the 2 medial nasal prominences at the midline. The canal marks the junction between the primary and secondary palates, the latter composed of palatine shelves growing from the maxillary prominences. The nasopalatine canal initially appears as a wide space but narrows and fills with fibrous tissue as the incisive bone ossifies at 12 to 15 weeks.[10]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The nasopalatine artery, also known as the sphenopalatine artery, is a branch of the internal maxillary artery.[11] The nasopalatine artery enters the nasal cavity via the sphenopalatine foramen to supply the frontal, maxillary, ethmoid, and sphenoid sinuses. One nasopalatine artery branch descends into the nasopalatine canal to anastomose with the descending palatine artery, entering the incisive foramen with the nasopalatine nerve.

The veins of the palate are diffuse and variable. The primary vessel draining this region is the facial vein, which courses from the medial canthus behind the facial artery and joins with the retromandibular vein below the mandible. This union is sometimes termed the "common facial vein." Venous drainage of the hard palate is via the pterygoid plexus of veins in the infratemporal fossa, while the soft palate empties via the pharyngeal venous plexus.

Lymphatics from the palate generally terminate in the jugulodigastric nodes. The drainage of the palatal gingivae varies, occurring directly via the jugulodigastric nodes or indirectly via the submandibular nodes. Posterior soft palate lymphatics drain into the pharyngeal lymph nodes.

Surgical Considerations

The nasopalatine nerve may be traumatized or dissected during surgery for removing supernumerary teeth. Younger patients have been shown to regain almost immediate sensation on the anterior palate after encountering such complications. In contrast, patients older than 14 do not show the same quick recovery. The nasopalatine nerve's contribution to the anterior palate's innervation seems to increase with age and maxillary development. Dysesthesia of the anterior palate or maxillary teeth may occur after septoplasty, mainly if the procedure addresses low septal spurs and uses cautery or osteotomes.[12]

The nasopalatine duct cyst is a developmental nonodontogenic maxillary cyst, arising from the nasopalatine duct's epithelial remnants that proliferate spontaneously or due to trauma, infection, or mucus retention. This lesion is the most common nonodontogenic maxillary cyst, occurring in 1% of the population, typically affecting middle-aged individuals. Treatment requires surgical excision via a sublabial or palatal approach. The cyst is not a true neoplasm and can thus also be treated by marsupialization to the nasal cavity.[13][14]

Clinical Significance

The nasopalatine nerve block is used to achieve soft tissue anesthesia for procedures involving the premaxilla, such as cleft palate repair. In some patients, this block can also anesthetize the pulp of the maxillary incisors. This procedure requires the deposition of the anesthetic solution in the incisive canal, resulting in bilateral anesthesia of the nasopalatine nerve and blocking pain fibers in the palatal mucosa of the anterior 6 maxillary teeth.

The technique traditionally involved a single penetration into the canal, which was too traumatic and painful for the patient. The current practice entails multiple injections, with the first one performed on the labial side in the interdental papilla, entering horizontally with a 30-gauge needle. The solution diffuses to the palate after achieving buccal anesthesia. However, this block cannot be accomplished in patients with complete cleft palates, as they have malformed premaxillae.[15][16]

Nasopalatine canal measurement is also important in the field of implant dentistry, as it helps prevent intraoperative complications, such as a nasopalatine canal or buccal bone plate perforation. To date, traditional imaging modalities have proven ineffective, given the bony complexity of this region. Thus, cone beam computed tomography has seen increased use with success.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Freddi TAL, Ottaiano AC, Lucio LL, Corrêa DG, Hygino da Cruz LC Jr. The Trigeminal Nerve: Anatomy and Pathology. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2022 Oct:43(5):403-413. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2022.04.002. Epub 2022 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 36116853]

Scanavine AB, Navarro JA, Megale SR, Anselmo-Lima WT. Anatomical study of the sphenopalatine foramen. Brazilian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2009 Jan-Feb:75(1):37-41 [PubMed PMID: 19488558]

Demiralp KÖ, Kurşun-Çakmak EŞ, Bayrak S, Sahin O, Atakan C, Orhan K. Evaluation of Anatomical and Volumetric Characteristics of the Nasopalatine Canal in Anterior Dentate and Edentulous Individuals: A CBCT Study. Implant dentistry. 2018 Aug:27(4):474-479. doi: 10.1097/ID.0000000000000794. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30028392]

Souza SS, Raggio BS. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Sphenopalatine Foramen. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31751101]

Reed KL, Malamed SF, Fonner AM. Local anesthesia part 2: technical considerations. Anesthesia progress. 2012 Fall:59(3):127-36; quiz 137. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-59.3.127. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23050753]

Langford RJ. The contribution of the nasopalatine nerve to sensation of the hard palate. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 1989 Oct:27(5):379-86 [PubMed PMID: 2804040]

Helwany M, Rathee M. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Palate. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491749]

Liu J, Li X, Ma L, Pan J, Tang X, Wu Y, Hua C. A Hypothesis and Pilot Study of Age-Related Sensory Innervation of the Hard Palate: Sensory Disorder After Nasopalatine Nerve Division. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2017 Jan 29:23():528-534 [PubMed PMID: 28132066]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceToro-Tobon S, Manrique M, Paredes-Gutierrez J, Mantilla-Rivas E, Oh H, Ahmad L, Oh AK, Rogers GF. Pharyngeal Arches, Chapter 1: Normal Development and Derivatives. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2023 Oct 1:34(7):2237-2241. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000009374. Epub 2023 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 37264513]

Kim JH, Oka K, Jin ZW, Murakami G, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Ahn SW, Hwang HP. Fetal Development of the Incisive Canal, Especially of the Delayed Closure Due to the Nasopalatine Duct: A Study Using Serial Sections of Human Fetuses. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2017 Jun:300(6):1093-1103. doi: 10.1002/ar.23521. Epub 2017 Jan 27 [PubMed PMID: 27860365]

Otake I, Kageyama I, Mataga I. Clinical anatomy of the maxillary artery. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 2011 Feb:87(4):155-64 [PubMed PMID: 21516980]

Chandra RK, Rohman GT, Walsh WE. Anterior palate sensory impairment after septal surgery. American journal of rhinology. 2008 Jan-Feb:22(1):86-8. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3114. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18284865]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHonkura Y, Nomura K, Oshima H, Takata Y, Hidaka H, Katori Y. Bilateral endoscopic endonasal marsupialization of nasopalatine duct cyst. Clinics and practice. 2015 Jan 28:5(1):748. doi: 10.4081/cp.2015.748. Epub 2015 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 25918636]

Wu YH, Wang YP, Kok SH, Chang JY. Unilateral nasopalatine duct cyst. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan yi zhi. 2015 Nov:114(11):1142-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2015.08.005. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26329385]

Reena, Bandyopadhyay KH, Paul A. Postoperative analgesia for cleft lip and palate repair in children. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2016 Jan-Mar:32(1):5-11. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.175649. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27006533]

Echaniz G, De Miguel M, Merritt G, Sierra P, Bora P, Borah N, Ciarallo C, de Nadal M, Ing RJ, Bosenberg A. Bilateral suprazygomatic maxillary nerve blocks vs. infraorbital and palatine nerve blocks in cleft lip and palate repair: A double-blind, randomised study. European journal of anaesthesiology. 2019 Jan:36(1):40-47. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000900. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30308523]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence