Introduction

The utilization of opioids in clinical pharmacology started after the extraction of morphine from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum in 1806 with its use further intensified after the discovery of hypodermic needles in 1853.[1] Opioids divide into two types, those being endogenous and exogenous. Some endogenous opioids that bind to the receptors are enkephalins, endorphins, endomorphins, dynorphins, and nociception/orphanin. Exogenous opioids like morphine, heroin, and fentanyl are substances that are introduced into the body and bind to the same receptors as the endogenous opioids. To date, five types of opioid receptors have been discovered-mu receptor (MOR), kappa receptor (KOR), delta receptor (DOR), nociception receptor (NOR) and zeta receptor (ZOR). Within these different types are a subset of subtypes, mu1, mu2, mu3, kappa1, kappa2, kappa3, delta1, and delta2. This report focuses on the functioning and significance of opioid receptors.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

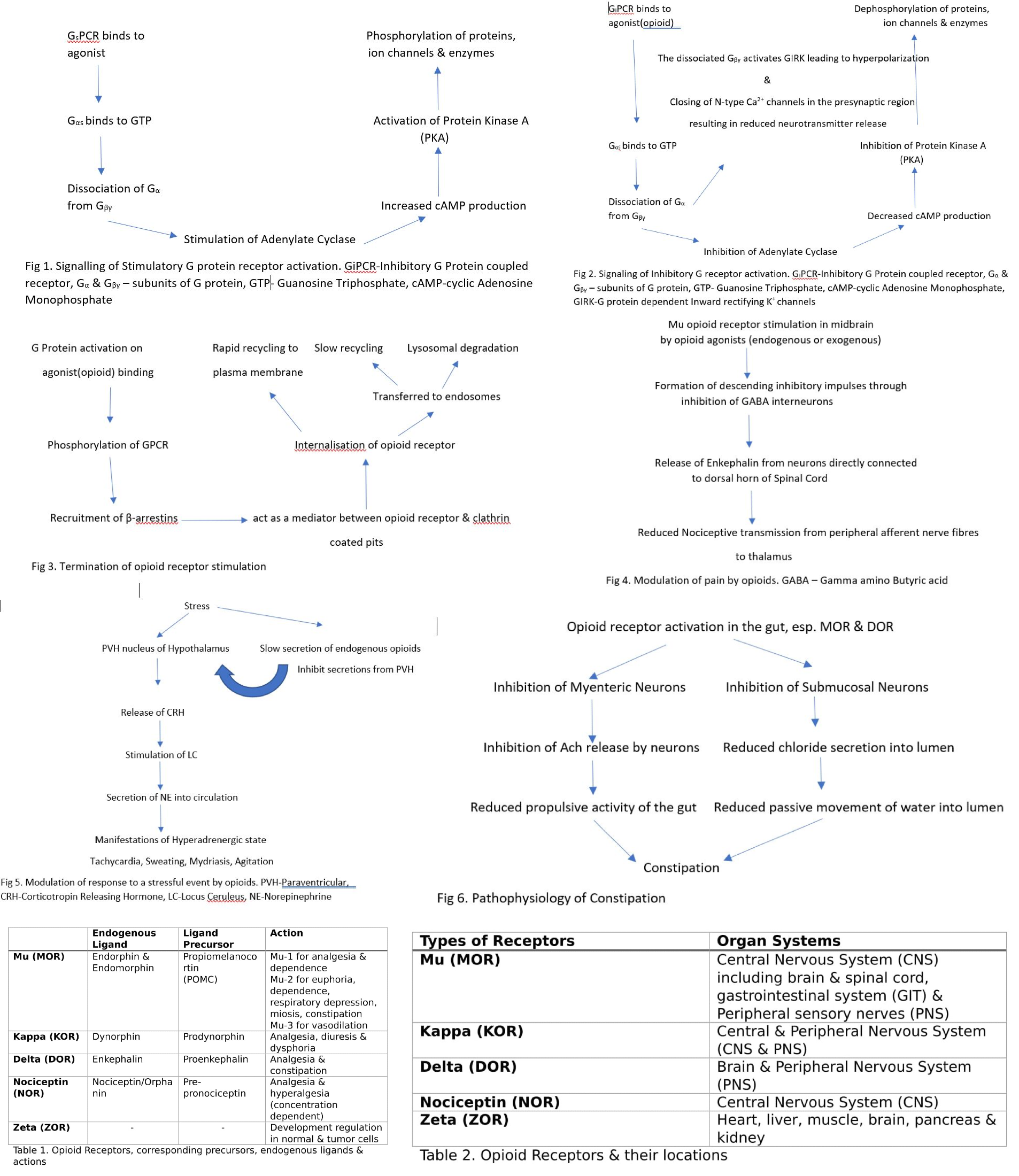

The different types of opioid receptors bind to their respective agonist counterparts. See Table 1-1

Mu1,2,3 receptors (MOR) bind to endogenous ligands - beta-endorphin, endomorphin 1 and 2 with proopiomelanocortin (POMC) being the precursor.

The mu-1 receptor is responsible for analgesia and dependence.

The mu-2 receptor is vital for euphoria, dependence, respiratory depression, miosis, decreased digestive tract motility/constipation

Mu-3 receptor causes vasodilation. Kappa receptors (KOR) bind to dynorphin A and B (Prodynorphin as the precursor). They provide analgesia, diuresis, and dysphoria.

Delta receptors (DOR) bind to enkephalins (precursor being Proenkephalin). They play a role in analgesia and reduction in gastric motility.

Nociceptin receptors (NOR) bind to nociceptin/orphanin FQ (Pre-pronociceptin is the precursor) causing analgesia and hyperalgesia (depending on the concentration).

Zeta receptors (ZOR) regulate developmental events in a variety of normal and tumorigenic tissues and cells.[1]

Cellular Level

Opioid Receptors are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). They mediate the human body's response to most hormones, neurotransmitters, drugs, and are involved in sensory perception of vision, taste, and olfaction.[2] All GPCRs consists of seven transmembrane spanning proteins that couple to intracellular G proteins. There are different types of G proteins bound to receptors which are differentiated based on the signaling pathways activated intracellularly. Gs protein-coupled receptors are considered stimulatory due to their activation of the molecule adenylate cyclase, which increases cAMP production. The molecule cAMP activates Protein Kinase A (PKA) that is responsible for phosphorylation of numerous proteins, ion channels, and enzymes ultimately resulting in their activation/inhibition.[3] (See Fig 1.)

The activation of cAMP is counteracted by a different type of G protein known as Gi protein, which couples to its ligand-binding receptor. (See Fig 2.) After binding of the opioid agonist (endogenous or exogenous) to the extracellular N-terminus domain of the receptor, G-alpha-i/o found on the intracellular C-terminus side of the receptor binds to GTP. This binding leads to its dissociation from G-beta-gamma, and these two subunits attach to different effector molecules until the GTP linked to G-alpha hydrolyzes, causing their re-association and eventual termination of the effect. (See Fig 3.) The inhibition of adenylate cyclase by G-alpha-i/o preventing cAMP production.[3] At the neuronal synapses, opioids work by both inhibitory and excitatory action at the presynaptic and postsynaptic junction.[4]

Recent advances in technology have elicited activation of G protein-dependent inward rectifying potassium channels (GIRK) on stimulation of GiCPR by agonists, including opioids through the interaction of the G-beta-gamma subunit to the Kir channels. An important concept worth noting is that these channels become activated by G-beta-gamma produced by Gi-coupled receptors, but not by Gs and Gq receptors. GIRKs are members of the inwardly rectifying potassium (Kir) family of ion channels consisting of Kir3.1, Kir3.2, Kir3.3 and Kir3.4 subunits which combine to form homo or heterotetramers producing GIRK channels. Of these four types, GIRK 2 (Kir3.2) is abundantly present in the nervous system and their activation by opioids leading to hyperpolarization of the neurons through increased outward K+ current mediating the inhibitory effects of the opioids.

N-type voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) are important targets of G-beta-gamma subunit of Gi-coupled receptor when stimulated by opioid agonists. These channels are present in the presynaptic region of neurons throughout the central and peripheral nervous system which when stimulated cause the influx of calcium into the presynaptic neuron ultimately resulting in the release of neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. The interaction of G-beta-gamma with N-type Ca2+ channels results in its inhibition and prevents the flow of Ca2+ current blocking the secretion of neurotransmitters.[5]

GPCRs are phosphorylated at serine and/or threonine residues at the C-terminus using G protein kinases after binding of these receptors with opioid agonists. Following the phosphorylation process, beta-arrestins are recruited, which terminate the G protein activation and initiate the internalization process through acting as a mediator in the interaction between the receptor and clathrin-coated pits. Furthermore, upon internalization, receptors can either undergo rapid recycling to the plasma membrane or transferred to the endosomes where they are slowly recycled or degraded into lysosomes.[6]

New and upcoming reports have documented modulation of MAPK/ERK pathway (Mitogen-activated protein kinase) which is involved in a variety of cellular processes including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.[3]

Development

Advancements in technological innovations like molecular docking, nanobodies, ultramicroscopic techniques, chemogenetics, and optogenetics have helped in identifying the crystal structure of the various opioid receptors and development of novel agonists.[7] Evolution of these techniques mentioned above and the discovery of new methods can undoubtedly aid in the production of drugs with increased analgesic effect and reduced adverse effects helping solve the opioid epidemic.

Function

Analgesia

The nervous system comprises a high concentration of opioid receptors in periaqueductal gray, locus ceruleus (LC), rostral ventral medulla, substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and the peripheral afferent nerves. The peripheral receptors sense painful stimuli, and impulses get carried to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord for relay to higher centers of the brain. MOR activation by an opioid agonist in the midbrain causes the formation of descending inhibitory impulses(mediated through inhibition of GABA interneurons) to the periaqueductal gray which stimulates descending inhibitory neurons[1] that trigger enkephalin-containing neurons connected directly with the dorsal horn, subsequently leading to decrease in nociceptive transmission from the periphery to the thalamus. (See Fig 4.) Exogenously administered opioids cause analgesia both through direct inhibition of substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horn and through peripheral afferent nerves.

Stress

MOR play a central role in toning down the central stress response through inhibition of secretion of norepinephrine (NE) from locus ceruleus (LC), attenuating the stressful state characterized by sustained release of NE under the effect of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH). (See Fig 5.) Therefore, MORs are instrumental in recovering from stress, demonstrated by the reduction in the risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) based on evidence obtained from studies showing the beneficial effect of morphine administration after a stressful event.[1]

Mood and Reward

Presence of high density of MOR in the limbic system (emotional center) regulates mood and rendering these receptors potential targets to treat mood disorders like anxiety and depression.

The reward center of the brain comprising of ventral tegmental area (VTA) that sends projections to the ventral striatum within the mesolimbic dopamine system. MOR stimulation, through its inhibition of GABA secretion, results in the release of dopamine. Dopamine is responsible for the rewarding effects produced by opioid administration, leading to positive reinforcement.[1]

Mechanism

Understanding the tools of the physiological functioning of opioid receptors is significant to develop new therapeutic drugs.

Heteromerisation

Heteromerisation of receptors is the interaction between different classes of receptors which on being co-stimulated invoke a functional response distinct from a response produced on their individual stimulation.

Interaction with other opioid receptors

Heteromers containing opioid receptors only are formed with different combinations including DOR-MOR, DOR-KOR, and MOR-KOR with DOR-MOR combination as the most well understood. Receptors can be stimulated independently or concurrently as heteromers depending on the binding agonist. Further research needs to be undertaken to tap this mechanism of heteromerization for therapeutic benefit.[3]

Interactions with Other GPCRs

CB1 Receptor

Some recent studies have shown the interaction of MORs with Cannabinoid (CB1) receptors; this has been observed through increased potency of opioids like morphine when co-administered with CB1 receptor agonist 9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Another point of evidence is the significant modulation of the ERK pathway on stimulation of MOR/CB1R heterodimer, compared to the modulation observed with individual receptor stimulation.

Studies have shown that interactions exist between MOR and alpha-2A adrenergic receptors altering the functional activity of these individual receptors. A significant interaction of MOR with the neurokinin-1 receptor (NK1) leads to changes in the internalization and resensitization processes.

Allosteric Modulation

Specific molecules that bind to sites on the receptors other than the ligand-binding sites, to potentially cause an alteration in the effects of the agonist receptor complex are referred to as allosteric molecules. These are either positive or negative allosteric modulators depending on the increase or decrease in the potentiation of effects of opioids agonists on binding opioid receptors, respectively. This modulation is a crucial aspect to unravel since, in addition to lowering of the required analgesic dose of the opioid, it reduces the likelihood of developing tolerance and dependence.[8]

Biased Signaling

Recent advances in the comprehension of the signaling pathways have unraveled the phenomenon of biased signaling. Biased signaling can be understood using the example of signaling pathways activated after binding of an agonist to KOR. KOR stimulation recruits G protein-coupled signaling pathway and beta-arrestin pathway, which leads to analgesic and dysphoric effects, respectively. This phenomenon has also been observed with MOR stimulation with analgesia undergoing mediation by Gi protein-coupled signaling and adverse effects like respiratory depression by beta-arrestin recruitment.[9]

Interaction with Other Cellular Proteins

Opioid receptors, particularly MOR, have been shown to interact with other cellular proteins like calmodulin (Ca2+ binding protein) and cytoskeletal trafficking proteins involved in the process of endocytosis.

Pathophysiology

Adverse Effects

Respiratory Depression

Opioid receptors are abundant in the respiratory center in the cerebral cortex, thalamus, peripheral chemo and baroreceptors in the carotid bodies and vagi, and mechanoreceptors of the airways and lungs. Stimulation of these receptors leads to irregular and slow breathing, eventually developing hypercapnia and hypoxia.

Constipation

Opioid receptors are widely distributed throughout the autonomic nervous system (ANS), especially making their presence felt in the gastrointestinal ANS. Opioid receptor activation by agonists causes slowing of propulsive motility of the gut mediated through inhibition of acetylcholine (ACh) by myenteric neurons and partially inhibiting purine and nitric oxide release from inhibitory motor neurons. Furthermore, their stimulation decreases chloride secretion through inhibition of secretomotor submucosal neurons, resulting in reduced passive water movement into the lumen, which causes the development of hardened stools leading to increased constipation.[10] See Fig 6.

Orthostatic Hypotension and Syncope

Opioid receptors are present in cardiac tissue; their activation leads to hyperpolarization of membranes and activation of the vagus nerve. These changes result in peripheral vasodilation and bradycardia, which ultimately causes hypotension. Peripheral vasodilation gets further exacerbated by systemic histamine release.

Endocrine Abnormalities

Stimulation of opioid receptors located in the hypothalamus inhibits GnRH release, which results in reduced estrogen and testosterone secretion. Hence, chronic activation of these receptors leads to osteoporosis and sexual dysfunction, presenting as decreased libido, infertility, and increased bone fragility.[11]

These receptors in the hypothalamus cause reduced the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, resulting in low levels of ACTH and cortisol. Low cortisol levels present clinically with nonspecific symptoms- anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue, lethargy, and fever.

Syndrome of Inappropriate ADH Secretion (SIADH)

Administration of opioids has also been documented in some case studies to cause ADH secretion from the posterior pituitary due to the stimulation of opioid receptors in the hypothalamus. The stimulation of these receptors leads to the inhibition of GABA, which removes the inhibitory effect of the neurotransmitter on the secretion of Anti-diuretic hormone (ADH). This hypersecretion of ADH can even lead to hyponatremia in severe cases. This phenomenon is unrelated to the well-established fact of increased ADH release in response to the nociceptive transmission.[12] SIADH observed with the use of opioids has rarely been observed, but the clinician should be concerned about the possibility of SIADH in patients presenting with reduced urine output and symptoms suggestive of hyponatremia after recent initiation of opioids.

Immune Dysfunction

Opioid receptors are present on immune cells, namely natural killer (NK) cells, and phagocytes, and their stimulation leads to repression of their activity resulting in blunting of the immune response and delayed wound healing.

Sleep Changes

Activation of opioid receptors in the medium pontine reticular formation alters normal sleep pattern. Opioid agonists through stimulation of these receptors increase the duration of light sleep, consequently decreasing deep and REM sleep duration.[11]

Mood Changes

Chronic stimulation of MOR reduces neuronal flexibility and production of neurons in the hippocampal region leading to mood dysregulation and eventually, social withdrawal.

Pathophysiology of Tolerance and Addiction

It is a reasonable inference that the most significant hindrance to the prescription of opioids as analgesics is the eventual development of tolerance to the opioid medications rendering them ineffective over prolonged durations. Chronic opioid administration has a propensity to lead to irreversible dysfunction of the endogenous opioid system making it inefficient to respond to the various stressors; this mainly occurs due to reduced production of endogenous opioids. The inability of the endogenous opioids to react appropriately to outside stressors will cause the users to ultimately become dependent on exogenous opioids to mimic the action elicited by the exogenous opioid system. Henceforth, this propels the increased risk of hyperalgesia, dependence, and when unchecked, eventually leading to addiction.

The molecular basis for the development of tolerance to opioids has been the topic of many studies. Earlier, it was believed to occur due to downregulation of MOR on chronic exposure to opioids, but recent evidence suggests that this phenomenon alone cannot explain opioid tolerance given that downregulation has been observed to occur inconsistently with different agonists. It can concur from various in vivo studies that desensitization and uncoupling of MOR from downstream signaling pathways and ion channels play an essential part in the development of tolerance. Observations have noted an increased concentration of cAMP in cells exposed to prolonged doses of morphine, which may be the result of cellular adaptive changes through increased activity of adenylyl cyclase and possibly other mediators of the pathway.[3]

Another type of molecules observed to be involved in desensitization of opioid receptors are beta-arrestins that cause internalization of receptors. In vivo studies performed using beta-arrestin-2 knockout mice have shown a failure to develop analgesic tolerance to chronic opioid administration. It has also been well documented that different agonists recruit different subtypes of arrestins suggesting desensitization and internalization are regulated by the type of agonist and the corresponding stimulated receptor. For example, morphine shows increased tolerance ability compared to other exogenous opioids due to its variable beta-arrestin recruitment activity. Furthermore, chronic exposure to opioids, either exogenous or endogenous leads to receptor phosphorylation on specific amino acid residues located on the intracellular C-terminus through activation of protein kinases, another phenomenon suspected to be responsible for tolerance development. Receptor phosphorylation recruits arrestin molecules which ultimately decide the fate of the G protein-coupled opioid receptor.[3]

As mentioned earlier, chronic opioid administration cuts down the endogenous opioid production, particularly in the locus cerulus resulting in increased secretion of NE. This high tonic secretion of NE even after the occurrence of a stressful event is considered pathological characterized by a state of agitation and hyperexcitability. Researchers have noted some form of discrepancy in the sensitivity of opioid receptors between genders. Women present with reduced opioid sensitivity compared to men resulting in higher excitability in response to stressors, but consequently, addiction is more prevalent amongst the male gender.

Clinical Significance

Opioids are administered abundantly by the medical fraternity around the world due to their excellent analgesic and other related uses, namely cough, diarrhea, mood disorders. Nonetheless, accompanying their therapeutic utility are adverse effects that limit their use in different settings. The recent opioid crisis has propelled researchers to search for innovative strategies to counter the rising epidemic by accelerating the development of new analogs with minimal tolerance, dependence, and other harmful effects. Comprehending the diversity of signaling at different types of opioid receptors and how intracellular mechanics lead to the regulation of pain and reward could reveal new and useful opioid receptor drug candidates. Further genetic research needs to be undertaken to recognize specific genetic variants associated with increased addiction potential to opioids.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Toubia T, Khalife T. The Endogenous Opioid System: Role and Dysfunction Caused by Opioid Therapy. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Mar:62(1):3-10. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000409. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30398979]

Rosenbaum DM, Rasmussen SG, Kobilka BK. The structure and function of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature. 2009 May 21:459(7245):356-63. doi: 10.1038/nature08144. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19458711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Hasani R, Bruchas MR. Molecular mechanisms of opioid receptor-dependent signaling and behavior. Anesthesiology. 2011 Dec:115(6):1363-81. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318238bba6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22020140]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYudin Y, Rohacs T. Inhibitory G(i/O)-coupled receptors in somatosensory neurons: Potential therapeutic targets for novel analgesics. Molecular pain. 2018 Jan-Dec:14():1744806918763646. doi: 10.1177/1744806918763646. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29580154]

Mochida S. Presynaptic calcium channels. Neuroscience research. 2018 Feb:127():33-44. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2017.09.012. Epub 2018 Jan 6 [PubMed PMID: 29317246]

Badal S, Turfus S, Rajnarayanan R, Wilson-Clarke C, Sandiford SL. Analysis of natural product regulation of opioid receptors in the treatment of human disease. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2018 Apr:184():51-80. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.10.021. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29097308]

Bruchas MR, Roth BL. New Technologies for Elucidating Opioid Receptor Function. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2016 Apr:37(4):279-289. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2016.01.001. Epub 2016 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 26833118]

Valentino RJ, Volkow ND. Untangling the complexity of opioid receptor function. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018 Dec:43(13):2514-2520. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0225-3. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30250308]

Conibear AE, Kelly E. A Biased View of μ-Opioid Receptors? Molecular pharmacology. 2019 Nov:96(5):542-549. doi: 10.1124/mol.119.115956. Epub 2019 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 31175184]

Farmer AD, Holt CB, Downes TJ, Ruggeri E, Del Vecchio S, De Giorgio R. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of opioid-induced constipation. The lancet. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2018 Mar:3(3):203-212. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30008-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29870734]

Tyan P, Carey ET. Physiological Response to Opioids. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Mar:62(1):11-21. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000421. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30668556]

Karahan S, Karagöz H, Erden A, Avcı D, Esmeray K. Codeine-induced syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone: case report. Balkan medical journal. 2014 Mar:31(1):107-9. doi: 10.5152/balkanmedj.2013.9424. Epub 2014 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 25207179]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence