Introduction

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) is a condition that characteristically presents with hip pain secondary to mechanical impingement from abnormal hip morphology involving the proximal femur and/or acetabulum. With hip rotation to extreme arcs of motion or when there is repetitive, abnormal contact between the bony prominences, this leads to soft tissue damage of the femoroacetabular joint. Over time, this chronic repetitive trauma can lead to hip pain and decreased function. The abnormal bony features include cam deformity of the femoral head-neck junction as well as pincer lesions of the acetabulum. Cam deformity is an abnormal bony prominence or "bump" at the junction of the femoral head and neck resulting in an aspherical-shaped head, occurring most commonly along the anterosuperior femoral head-neck area. A pincer lesion is an abnormal bony overhang of the anterolateral acetabular rim resulting in over coverage of the femoral head, which can also contribute to impingement and pain. Both cam and pincer lesions are visible on plain radiographs (X-ray). Patients may present with either one or both (mixed) morphologies, with the mixed morphology being the most common in symptomatic patients. When impingement occurs, it results in a mechanical collision of the femoral cam with the rim of the acetabulum, which results in pinching of the labrum and cartilage. Over time, this can result in cartilage wear and tearing of the labrum.[1]

As a result of labral and cartilage injury, FAI can lead to hip osteoarthritis over time. The diagnosis of this condition is dependent on history, physical exam, and radiography of the hip and pelvis. Treatment typically consists of initial non-operative measures; however, if conservative management fails, then there should be consideration of surgical management by an orthopedic surgeon.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of femoroacetabular impingement is still under investigation; however, studies suggest that genetic factors may contribute to abnormal hip pathology. Multiple studies have investigated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) such as GDF5, FRZB, DIO2, and HOX9.[2][3] FRZB has been found by one study to contribute to a specific shape of proximal femur morphology on X-ray and increased development of osteoarthritis of the hip.[4] DIO2 has also correlated with specific proximal femur morphology and the increased development of hip osteoarthritis.[5] HOX9 was looked at in a Japanese population and found to contribute to pincer lesion formation of the acetabulum.[5]

There is also evidence to suggest an increased incidence of FAI in athletes due to cam deformity formation.[5][6] More specifically, adolescents engaged in high-intensity sports were found to be ten times more likely to have a cam deformity and impingement than age-matched adolescents not participating in high-intensity sports.[5] There is a theory that increased stress along the growth plate of the hip leads to increased stress reaction bone formation resulting in cam deformity and subsequent impingement.

The formation of FAI has also occurred in patients with a history of slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). When this primary insult happens during childhood, the epiphysis of the femoral head slips posterior and medial respective to the metaphysis, leading to a prominent metaphysis anterior and laterally. Even after surgical in situ fixation of a slipped capital femoral epiphysis, there is a residual deformity, and this can cause impingement.[7]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement in the general adult population is between 10 to 15%. Based on clinical diagnosis, FAI affects adolescents and the young adult population before radiographic signs of arthritis manifest.[8] The prevalence of symptomatic athletes has been reported to be higher than the general population at 55%.[9] There is also literature that has examined the prevalence of anatomic morphology consistent with this condition but in asymptomatic individuals; therefore, patients can have bony features of FAI and not manifest with symptoms. A meta-analysis by Frank et al. reports a prevalence of 37% for cam deformity and 67% for pincer deformity in asymptomatic volunteers.[10] When accounting for the athletic population, cam deformity prevalence was 54.8% for athletes and 23.1% for non-athletes. The pincer lesion was present in 49.5% of the athletic population. Cam deformity is more prevalent in men than women, with a reported prevalence of 9 to 25% men versus 3 to 10% in women. Pincer lesions are more common in women than men, with reports of 19.6% versus 15.2%.[11]

History and Physical

Obtaining a thorough history is essential for identifying a diagnosis for hip pain. Inquiring about a history of trauma, infection, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, Legg-Calve-Perthes disease, hip dysplasia, osteonecrosis, sporting activities, and any other hip pathology is essential for workup. Femoroacetabular impingement characteristically presents with a gradual onset of hip pain, often exacerbated by hip flexion and internal rotation. Activities such as high-intensity sports, squatting, driving, and even sitting for prolonged periods may provoke hip pain. If a patient presents with acute hip pain, a workup for other causes is necessary. Clinically, patients will present with groin or hip pain anterolaterally that may radiate to the thigh and may convey the location of their pain with a "C sign," which is formed by the index finger and thumb over the anterolateral aspect of the hip. Common associated complaints include clicking, popping, and catching, which raises the suspicion for a labral injury.[12]

Physical examination of the patient with hip pain encompasses gait observation, hip range of motion and strength, and special exam maneuvers to help determine the likely cause. Trendelenburg gait or abductor lurch indicates abductor muscle weakness or insufficiency. Hip range of motion in patients with FAI typically demonstrates decreased hip flexion and internal rotation as well as a positive impingement sign. A positive anterior impingement sign is marked by pain with hip flexion at 90 degrees, adduction, and internal rotation. This sign is present in 88% of patients.[13] The FABER test (hip Flexion, ABduction, and External Rotation) is performed to assess for labral pathology. Since impingement can result in a labrum tear, this test is frequently positive too. There may be palpable or audible snapping of the hip detected with the hip range of motion indicating snapping hip syndrome from either the iliopsoas tendon in the groin (internal snapping) or the iliotibial band along the greater trochanter (external snapping). It is essential to distinguish this from impingement, although both may occur together.[12]

Evaluation

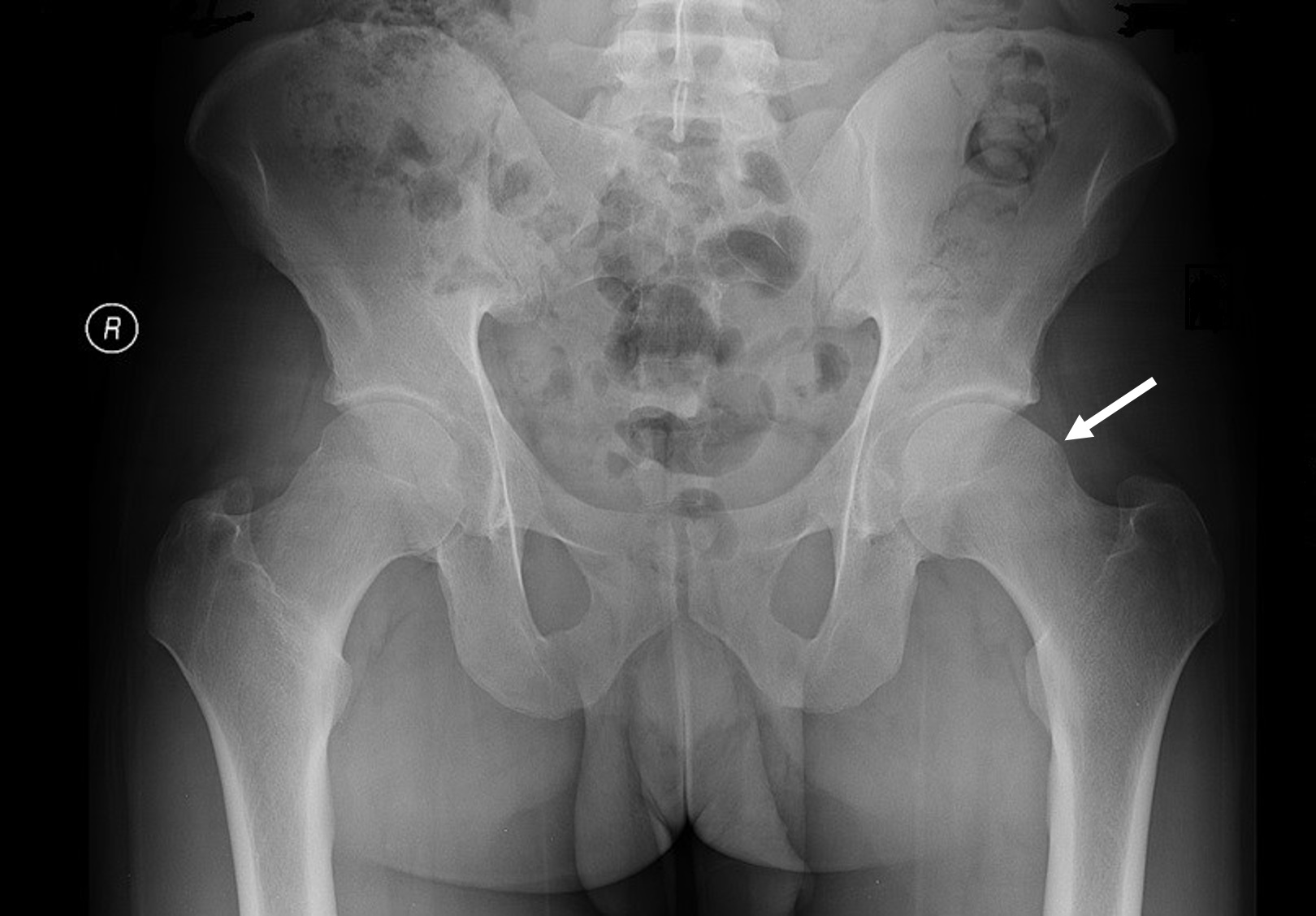

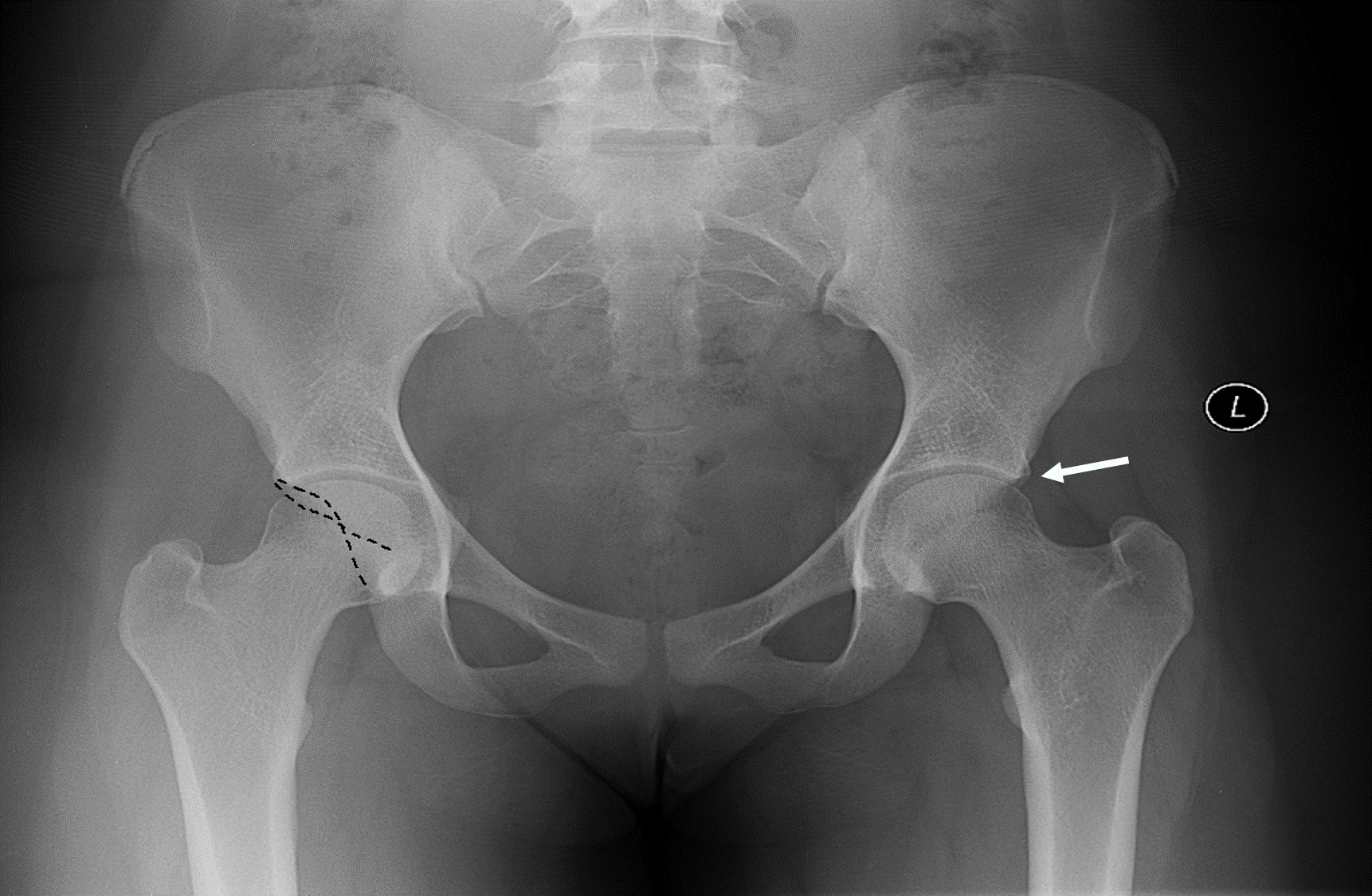

Once the history and physical exam confirm suspicion for femoroacetabular impingement or any hip pathology for that matter, radiographic evaluation of the hip with X-rays is the initial step. At a minimum, X-rays should include a standing anterior-posterior (AP) pelvis, AP hip, and lateral of the hip. These views allow the physician to assess the pelvis and proximal femur anatomy. Standing films help determine the position of the hip at a functional load-bearing position, which also helps detect arthritis of the hip or hip dysplasia. Cam and pincer lesions are identifiable on these X-ray views. The lateral center edge angle (LCEA) is also measured to assess for hip dysplasia. The lateral center edge angle is formed by a vertical line from the center of the femoral head and a line to the lateral edge of the acetabulum. An angle less than 25 degrees is indicative of hip dysplasia or lack of lateral femoral head coverage by the acetabulum. This condition is critical to identify since hip dysplasia can also manifest with intraarticular hip pain. Pincer deformity will present as an excess bony growth along the edge of the acetabulum, and a cam deformity will demonstrate as an excess bony growth along the femoral head-neck junction laterally or loss of sphericity of the head. Retroversion of the acetabulum can also be a cause for anterior impingement as this manifests with an overhanging acetabular rim and a crossover sign on the AP pelvis.[12]

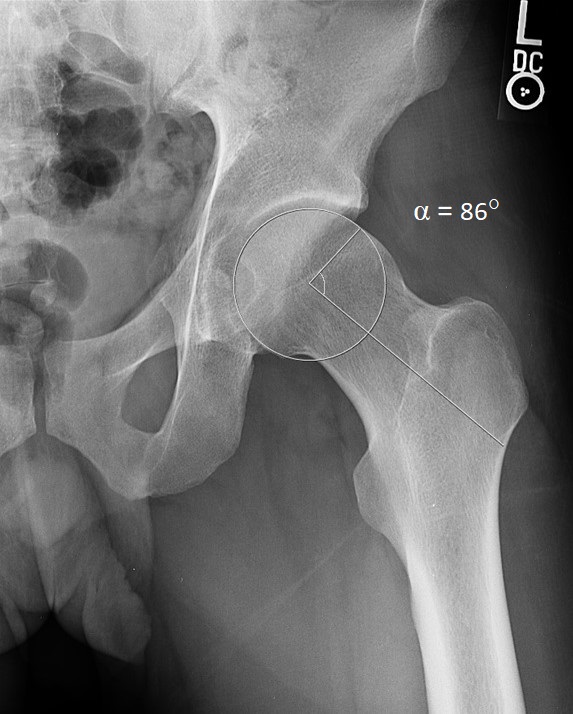

Other views commonly obtained to assess femoroacetabular impingement include the false profile and the Dunn views of the hip. To obtain a false profile view, the patient standing at an angle of 65 degrees from the cassette as the X-ray beam is directed towards the affected hip. This view can help assess the amount of anterior acetabular coverage of the hip by measuring the anterior center edge angle (ACEA); this is measured by an angle formed by a vertical line from the center of the femoral head and line from the center of the femoral head to the anterior acetabular rim. An angle of less than 25 degrees is indicative of poor anterior coverage consistent with hip dysplasia. Pincer deformity will demonstrate an increased angle (greater than 40 degrees) because of over coverage, coxa profunda, or protrusio acetabuli. The Dunn view is a lateral view of the affected hip which can be obtained at a 45-degree angle to the hip. This view best assesses the cam deformity along the anterolateral aspect of the femoral head-neck junction. The alpha angle measurement determines the extent of the cam lesion and is measured by a line in the center of the neck axis to the center of the femoral head, and another line from the center of the femoral head to the point of the anterior femoral head where normal sphericity is lost. Abnormal alpha angle measurements are over 50 degrees and indicate a cam deformity.[12]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with or without intra-articular contrast injection, is also utilized to assess FAI. This imaging modality can provide valuable information about potential labral or cartilage injury from impingement. It also offers 3D imaging of bony morphology and the presence of impingement cysts in the femoral neck. Other possible sources of hip pain can be identified such as avascular necrosis, stress fractures, greater trochanteric bursitis, abductor tendonitis, and iliopsoas tendinitis.[12]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of FAI consists of both non-operative and surgical options. Non-operative measures should be initiated before consideration of surgery. Such treatment options include physical therapy, activity modification, and pain medication (primarily with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). There is also a consideration for intraarticular injection with a combination of local anesthetic and steroid. This can be helpful for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes as successful pain relief from the injection would confirm the diagnosis and etiology of pain. If the patient has failed conservative treatment and the pain is affecting their quality of life, then surgical treatment should be considered.[1]

Surgical management consists of resecting the bony causes of impingement and repairing soft tissue structures as needed. Surgery can be performed arthroscopically or using an open technique. In the presence of a cam lesion involving the femoral head-neck junction, a cam resection or femoral osteoplasty is performed by using a high-speed burr to shave down the excess bone. When a pincer lesion is present on the acetabulum, an acetabular osteoplasty is performed. By removing the excess bone causing impingement, the patient can have an improved range of motion without pain. It is not uncommon for the labrum to be torn as well as a result of impingement.[14] Thus, when recognized, the labrum can be repaired if considered reparable, or simply debrided if repair is not feasible. Focal cartilage damage can be identified occasionally as a result of impingement. In this scenario, microfracture can be performed to stimulate new cartilage growth; however, this creates fibrocartilage rather than articular cartilage.

If hip arthritis is present on imaging, then these procedures should not be performed as they do not address pain from arthritis, and the patient will continue to have hip pain after surgery. Thus, patients with hip arthritis and FAI should be treated for hip arthritis. If severe arthritis is present, then the patient may be considered for hip replacement after conservative treatment is exhausted. Occasionally, patients may present with hip dysplasia and FAI (cam lesions), and both pathologies should be addressed for optimal outcomes. Hip dysplasia is addressed surgically with a pelvic osteotomy to improve femoral head coverage with the acetabulum.[12] There are many described pelvic osteotomies, but the periacetabular osteotomy is the most commonly utilized technique in skeletally mature patients, by reorienting the acetabulum to increase coverage of the femoral head. Some surgeons will perform both surgeries in one sitting; others will stage it within a week.

Traditionally, osteoplasty of the femur and pelvis has been performed by open surgical dislocation of the hip. However, hip arthroscopy is becoming a more common avenue for achieving the desired outcome, with arguably decreased surgical risks and complications. Open surgical dislocation provides better visualization, and allows more exposure to perform the osteoplasty; however, recovery is longer because of more extensive soft tissue dissection. Hip arthroscopy is a growing surgical technique in orthopedics that minimizes soft tissue disruption, but it is much more technically challenging. Arthroscopic outcomes are similar to open techniques for FAI.[14]

Differential Diagnosis

It is crucial to distinguish femoroacetabular impingement from other conditions that can cause hip pain. Perhaps, the most important conditions to identify are infection, tumor, and fracture. Septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or soft tissue infection will typically present with acute pain, inability to bear weight and fever. X-ray and MRI are useful tools for identifying these causes. Labs such as CBC, CRP, and ESR can also help distinguish infectious causes. Fractures and tumors are recognizable with an X-ray, CT scan, and MRI. Serum or urine laboratory tests could also prove useful for diagnosing certain types of tumors.

Other hip conditions that are less urgent to address, but must be distinguished from FAI include osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis) of the femoral head, hip dysplasia, iliopsoas tendinitis, greater trochanteric bursitis, gluteal tendinopathy, arthritis, iliotibial band syndrome, snapping hip syndrome, and lumbar radiculopathy.[12] Osteonecrosis can be identified on MRI with edema involving the femoral head. If collapse or sclerosis is present, this may be seen on X-ray, CT, and MRI. Hip dysplasia is identified on X-ray as a shallow acetabulum and/or poor femoral head coverage. Iliopsoas tendinitis or internal snapping hip syndrome is identified clinically when snapping or popping is heard or felt within the medial groin. MRI findings may show edema at the tendinous insertion of the lesser trochanter. Greater trochanteric bursitis and gluteal tendinopathy often occur together and present with pain laterally over the greater trochanter, often described as greater trochanteric pain syndrome. Hip abductor weakness may be present with gluteal tendinopathy or tears. MRI will show edema around the greater trochanter and tendon insertion of the gluteus medius and minimus muscles. In external snapping hip syndrome, the iliotibial band is tight and snapping over the greater trochanter causing pain, and can be diagnosed clinically. Arthritis will manifest with hip pain and evidence of decreased joint space because of cartilaginous wear on weight-bearing X-rays. Spinal etiology is important to identify as well. Lumbar radiculopathy from spinal stenosis can result in groin or hip pain when nerve roots are compressed (usually involving the L1 nerve root). A history of back pain and numbness or tingling in the extremity is important information to obtain.

Prognosis

Femoroacetabular impingement correlates as a risk factor for the development of osteoarthritis of the hip since bony impingement can cause soft tissue and cartilage injury of the hip. The thinking is that surgery for this condition could potentially delay the onset of arthritis. Since surgery for this condition is still relatively new, there is limited long-term outcome data. More mid-term data is readily available, including a meta-analysis comparing open and arthroscopic treatments.[15] This study has shown promising results for both open and arthroscopic procedures showing over 90% survivorship around five years. Future studies are warranted to look at more long-term data.

Complications

Complications associated with surgery for femoroacetabular impingement can organize into major and minor complications. Significant complications include femoral neck fracture from excess resection of a cam lesion and abdominal compartment syndrome from inadvertent fluid extravasation during hip arthroscopy. During femoral osteoplasty (cam resection), recommendations are that no more than 30% of the neck gets resected as this dramatically increases the risk for a femoral neck fracture.[16] Other major complications include pulmonary embolism, deep infection of the joint, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, and postoperative dislocation.

Minor complications include hematoma, deep vein thrombosis, numbness and discomfort in the lateral thigh from injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve during portal placement or instrument passage, temporary perineal numbness (from traction against a post during arthroscopy), dyspareunia, superficial infection, and heterotopic ossification (abnormal location of bone formation around the hip). The most common complications of hip arthroscopy are hematoma and traction neuropraxia. Heterotopic ossification can be prevented or reduced by postoperative non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications such as indomethacin.[17]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients who undergo surgery for femoroacetabular impingement will typically experience a rehabilitation protocol that initially protects their weight-bearing status anywhere from 2 to 6 weeks. The specific weight-bearing restrictions vary amongst surgeons. Protected weight bearing is done to prevent stress upon any osteoplasty of the femur or acetabulum as well as protect any labrum repair. Physical therapy is initiated early with emphasis on passive range of motion of the hip for the first 3 to 4 weeks. Then weight-bearing status is advanced, and an active range of motion commences at around four weeks after surgery. Between 4 to 8 weeks, strengthening and gait training starts. At 8 to 12 weeks, there is an emphasis on the restoration of complete hip strength, core strength, balance, and proprioception. After 12 weeks, there is the incorporation of jogging, jumping, and agility exercises. The goal is to prepare the patient for return to play in sports or other exercise activities.[18]

Consultations

Physical therapy consultation is necessary for the initial treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Orthopedic surgery consultation by a surgeon who manages this condition should also be obtained for both conservative and surgical management.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with femoroacetabular impingement should receive education about the risk of developing osteoarthritis in the future as there is evidence to show that it is a risk factor, regardless of what treatment they obtained, whether non-operative or surgical.[19] While surgery can be performed to treat symptoms and improve patient quality of life, it is still unclear whether it will delay or prevent the development of hip arthritis. Patients should understand that despite having surgery, they may still develop arthritis in the future, have arthritic pain, and possibly requiring a hip replacement.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Treatment of femoroacetabular impingement involves a healthcare team approach from physicians, nursing staff, and therapists. The condition is often first recognized by primary care physicians/nurse practitioners after evaluation, and imaging is obtained, confirming the presence of FAI. Referral to an orthopedic surgeon is recommended at this point. Treatment, whether it involves surgery or conservative measures, will primarily be the decision of the orthopedic surgeon.

Conservative treatment is initiated first and usually involves physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications, hip injections, or a combination of these modalities. If conservative treatment fails, then surgery is a potential option for patients, which is performed by an orthopedic surgeon who typically has subspecialty training in hip preservation or hip arthroscopy. Physical therapists are a critical factor in the rehabilitation of patients after surgery as they help patients regain hip range of motion, strength, balance, coordination, and eventually, the ability to return to exercise or sports.[17] [Level III] Nurses, particularly those with specialized orthopedic training, play a significant role in facilitating follow-up with physicians, arranging therapy, and addressing patient concerns. Through a robust interprofessional team approach and collaboration amongst healthcare professionals, an excellent outcome is achievable for patients. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sankar WN, Nevitt M, Parvizi J, Felson DT, Agricola R, Leunig M. Femoroacetabular impingement: defining the condition and its role in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013:21 Suppl 1():S7-S15. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-07-S7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23818194]

Waarsing JH,Kloppenburg M,Slagboom PE,Kroon HM,Houwing-Duistermaat JJ,Weinans H,Meulenbelt I, Osteoarthritis susceptibility genes influence the association between hip morphology and osteoarthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2011 May; [PubMed PMID: 21400473]

Sekimoto T,Kurogi S,Funamoto T,Ota T,Watanabe S,Sakamoto T,Hamada H,Chosa E, Possible association of single nucleotide polymorphisms in the 3' untranslated region of HOXB9 with acetabular overcoverage. Bone [PubMed PMID: 25833894]

Baker-Lepain JC, Lynch JA, Parimi N, McCulloch CE, Nevitt MC, Corr M, Lane NE. Variant alleles of the Wnt antagonist FRZB are determinants of hip shape and modify the relationship between hip shape and osteoarthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012 May:64(5):1457-65. doi: 10.1002/art.34526. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22544526]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePacker JD,Safran MR, The etiology of primary femoroacetabular impingement: genetics or acquired deformity? Journal of hip preservation surgery. 2015 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 27011846]

Siebenrock KA, Ferner F, Noble PC, Santore RF, Werlen S, Mamisch TC. The cam-type deformity of the proximal femur arises in childhood in response to vigorous sporting activity. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2011 Nov:469(11):3229-40. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1945-4. Epub 2011 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 21761254]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKlit J, Gosvig K, Magnussen E, Gelineck J, Kallemose T, Søballe K, Troelsen A. Cam deformity and hip degeneration are common after fixation of a slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Acta orthopaedica. 2014 Dec:85(6):585-91. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.957078. Epub 2014 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 25175666]

Tanzer M, Noiseux N. Osseous abnormalities and early osteoarthritis: the role of hip impingement. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2004 Dec:(429):170-7 [PubMed PMID: 15577483]

Lee WY, Kang C, Hwang DS, Jeon JH, Zheng L. Descriptive Epidemiology of Symptomatic Femoroacetabular Impingement in Young Athlete: Single Center Study. Hip & pelvis. 2016 Mar:28(1):29-34. doi: 10.5371/hp.2016.28.1.29. Epub 2016 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 27536641]

Frank JM,Harris JD,Erickson BJ,Slikker W 3rd,Bush-Joseph CA,Salata MJ,Nho SJ, Prevalence of Femoroacetabular Impingement Imaging Findings in Asymptomatic Volunteers: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic [PubMed PMID: 25636988]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGosvig KK, Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Palm H, Troelsen A. Prevalence of malformations of the hip joint and their relationship to sex, groin pain, and risk of osteoarthritis: a population-based survey. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2010 May:92(5):1162-9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01674. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20439662]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePun S, Kumar D, Lane NE. Femoroacetabular impingement. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, N.J.). 2015 Jan:67(1):17-27. doi: 10.1002/art.38887. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25308887]

Clohisy JC,Knaus ER,Hunt DM,Lesher JM,Harris-Hayes M,Prather H, Clinical presentation of patients with symptomatic anterior hip impingement. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2009 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 19130160]

Dukas AG, Gupta AS, Peters CL, Aoki SK. Surgical Treatment for FAI: Arthroscopic and Open Techniques for Osteoplasty. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2019 Jul 1:12(3):281-290. doi: 10.1007/s12178-019-09572-4. Epub 2019 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 31264173]

Nwachukwu BU, Rebolledo BJ, McCormick F, Rosas S, Harris JD, Kelly BT. Arthroscopic Versus Open Treatment of Femoroacetabular Impingement: A Systematic Review of Medium- to Long-Term Outcomes. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Apr:44(4):1062-8. doi: 10.1177/0363546515587719. Epub 2015 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 26059179]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMardones RM, Gonzalez C, Chen Q, Zobitz M, Kaufman KR, Trousdale RT. Surgical treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: evaluation of the effect of the size of the resection. Surgical technique. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2006 Mar:88 Suppl 1 Pt 1():84-91 [PubMed PMID: 16510802]

Schüttler KF, Schramm R, El-Zayat BF, Schofer MD, Efe T, Heyse TJ. The effect of surgeon's learning curve: complications and outcome after hip arthroscopy. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2018 Oct:138(10):1415-1421. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2960-7. Epub 2018 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 29802454]

Domb BG,Sgroi TA,VanDevender JC, Physical Therapy Protocol After Hip Arthroscopy: Clinical Guidelines Supported by 2-Year Outcomes. Sports health. 2016 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 27173983]

Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Nötzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2003 Dec:(417):112-20 [PubMed PMID: 14646708]