Introduction

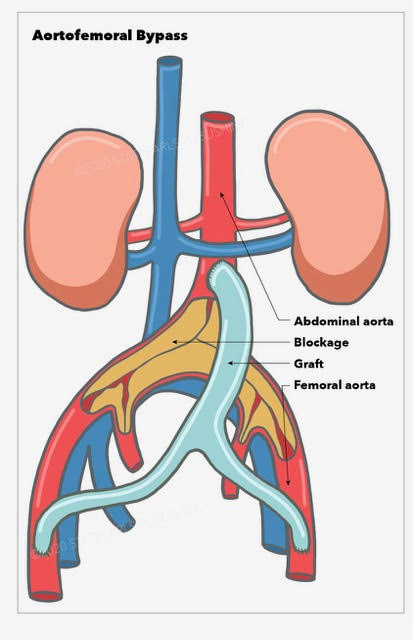

Aortofemoral bypass surgery is a procedure utilized commonly for the treatment of aortoiliac occlusive disease, sometimes referred to as Leriche syndrome.[1] Aortoiliac occlusive disease can contribute to lower extremity ischemic symptoms necessitating intervention. Symptoms of patients with aortoiliac occlusive disease may include claudication, rest pain of the lower extremities, or ischemic ulcer formation on lower extremities due to inadequate blood flow. However, patients may also be asymptomatic. An ankle-brachial index is the most widely used test to determine peripheral arterial disease initially. Aortofemoral bypass surgery has aided in the management of aortoiliac occlusive disease dating back to the early 1950s. More recently, revascularization with endovascular interventions has supplanted the aortofemoral bypass surgery as first-line therapy. However, in cases where endovascular techniques are unsuccessful or inappropriate, aortobifemoral bypass still plays an important role and can even be considered the gold standard for long term patency.[2] This will discuss the relevant anatomy, indications, contraindications, as well as some important technique considerations.[3][4][5]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Essential anatomy relevant to the aortofemoral bypass includes the aorta which bifurcates into the right and left common iliac arteries. The right and left common iliac arteries (CIA) subsequently branch into the right and left external (EIA) and internal iliac arteries (IIA). The external iliac arteries give rise to the common femoral arteries (CFA). Aortoiliac occlusive disease can occur anywhere along these arteries and vary in degree. It is important to comprehend the anatomical relationship of these structures for the disease process, procedure, and where an anastomosis might occur as well as where clamps would need to be applied.[2][3][4][6] The most common mode to visualize these structures is with CT angiography, which can also be used to create 3D reconstructions of the anatomy.[7]

Indications

In cases of aortoiliac occlusive disease, classic indications for surgical intervention include the following[1]:

- Iliac artery or abdominal aorta severe atherosclerosis causing symptoms

- Acute occlusion of iliac arteries or abdominal aorta

- Severe symptoms of claudication despite optimal medical therapy

- Gangrene of leg, nonhealing ulcers

- Critical limb ischemia, which can present as rest pain or severe claudication symptoms.

- Impotence

Before the surgical intervention, a trial of smoking cessation, regular exercise, antiplatelet therapy, weight loss, treatment of underlying hyperlipidemia, hypertension, diabetes is in order.[8]

A classification system termed the Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus was created to help clinicians determine if an open or endovascular technique was best suited for patients based on the morphological classification of their lesions.[9] The system provides a means to classify and categorize atherosclerotic lesions involving the aortoiliac, femoropopliteal, and infrapopliteal regions. It takes into account the extent of stenosis, presence of calcification, as well as laterality, length, and complexity of the lesions. The lesions are classified in categories A-D, as defined below. Typically type A & B are preferably managed endovascularly, whereas type C (in low-risk patients) and type D classifications are candidates for management with surgical bypass.[5][6][10][11] Although this is true, there are some instances were even Type C and D lesions undergo treatment with endovascular therapy. And patients should all be considered for endovascular therapy before surgery.[12] Patients undergoing endovascular techniques had overall lower costs, shorter length of stay, and lower complications rates. The mortality was not measured to be significantly different between the endovascular group (1.8%) and open group (2.5%).[13] There are also some cases being repaired laparoscopically, primarily in Europe.[14]

Type A Lesions

- CIA unilateral or bilateral stenosis;

- EIA single lesion of unilateral or bilateral <3cm stenosis.

Type B Lesions

- Stenosis less than 3m involving the infrarenal aorta

- CIA unilateral occlusion

- EIA with unilateral single/multiple areas of stenosis (totaling 3 to 10cm), sparing CFA

- EIA with unilateral occlusion (sparing origins of IIA or CFA)

Type C Lesions

- Bilateral CIA occlusion

- Bilateral EIA stenosis of 3 to 10cm, sparing CFA

- Unilateral EIA stenosis with the inclusion of ipsilateral CFA

- Unilateral EIA occlusion with the inclusion of origin of IIA and/or CFA

- EIA occlusion with heavy calcification with/without associated inclusion of IIA and/or CFA

- Occlusion of the infrarenal aortoiliac region

- Disease diffusely involving the aorta and bilateral CIA

- Multiple diffuse areas of stenosis including unilateral CIA and ipsilateral EIA, CFA

- Occlusion of unilateral CIA and ipsilateral EIA

- Occlusion of Bilateral EIA

- Iliac stenosis with co-existing AAA requiring treatment, but is unamenable to endograft

- Lesions necessitating open aortic or iliac surgery

Contraindications

An absolute contraindication to aortofemoral bypass includes any patient who is too unfit for general anesthesia. Some patients who are ineligible for aortofemoral bypass, are candidates to undergo axillofemoral bypass. However, the discussion of that surgery is outside the scope of this article.[15]

Relative contraindications or patients who are at increased risk of complications from having the aortofemoral bypass surgery include those with significant heart disease, recent cerebrovascular accident, recent myocardial infarction, multiple previous abdominal surgeries, retroperitoneal fibrosis, or horseshoe kidney. Also, end-stage renal disease patients are a high-risk operative group.[15]

Equipment

For the procedure, the surgeon will benefit from having a specialized vascular tray, which will include vascular (typically atraumatic) clamps, vessel loops, specialized needle drivers, and fine forceps (Geralds). They will also require a graft to form the bypass, which is likely to be supplied by different manufacturers at your facility. The graft that is available at a given hospital is dependent on which manufacturer has privileges at the hospital or operative facility. The surgeon will also require suture for the anastomosis of the graft to the native vessel. Patients will also require heparin during the procedure. Heparin administration is standard prior to clamping any of the blood vessels to help prevent thrombosis. Usually, protamine is administered towards the end of the case for the reversal of the anticoagulant effect. At the end of the procedure, it is often beneficial to have various hemostatic agents readily available should they be needed.

Personnel

To perform the procedure, the surgeon will need to have adequate experience in vascular surgery (usually fellowship training) and personnel trained in recognizing and utilizing the materials necessary for the procedure.

Preparation

In preparation for the procedure, you should ask your patient to partake in[16]:

- Tobacco cessation at least 3 to 4 weeks before surgery

- Exercising

In addition to specific patient preparation, the surgeon should also have on hand[17][18]:

- Blood on call to the operating room for the patient, should it be needed, (with cell saver available)

Addition, pre-operative stress testing, cardiac angiography, or intervention (open or percutaneously) have reduced mortality for aortic operations.[19]

Perioperative antibiotics should be administered to help decrease surgical site wound infections.[20]

Technique or Treatment

For an open technique, the patient positioning is supine with arms abducted to 90 degrees. The patient should undergo prepping from the nipples to the knees. The CFA, superficial, and deep femoral arteries bilaterally are isolated through bilateral groin incisions. It is essential to be sure that the distal portions of the vessels are soft, so they are suitable for clamping. Aortic exposure is typically through a midline incision (transperitoneal approach); however, some prefer a retroperitoneal approach or transverse incision. The retroperitoneum is entered, typically infracolically and after the duodenum is mobilized to the right. The aorta gets dissected below the level of the renal arteries. Most try to remain to the right of the inferior mesenteric vein to avoid violation of the left mesocolon. The renal vein can be mobilized by ligation of its tributaries. Exposure of the aorta needs to be taken down to the level of the inferior mesenteric artery. Tunnels within the retroperitoneum, posterior to the ureters are carried down to the groin incisions. On the left side, the tunnel is often brought posterior to the inferior mesenteric artery to help with keeping the graft isolated from the left mesocolon.[17][21][16] Heparin is administered (70 to 100 units/kg) with goal ACT 250 to 300 seconds, and then the aorta is clamped below the renal arteries and on the distal portion already exposed.[22][23][24] The surgeon divides the aorta and a portion resected proximal to the inferior mesenteric artery. The distal aorta is oversewn. The chosen graft is anastomosed to the proximal aorta, most commonly in an end-to-end fashion using a 3-0 or 4-0 running permanent suture.

The limbs of the graft are then flushed with heparinized saline, clamped and passed through the tunnels into the groin incisions. Clamps are applied to the CFA, and an arteriotomy is made, sometimes down to the level of the profunda, thus requiring a profundaplasty. Endarterectomy follows, if necessary. The graft is anastomosed to the CFA in an end-to-side running manner usually with 4-0 or 5-0 permanent suture. Before completion of the anastomosis, usual backbleeding, forward bleeding and flushing are employed. The opposite femoral artery is done similarly. Blood flow is restored to the CFA, then profunda femoris, and lastly the superficial femoral artery. However, before unclamping, anesthesia should be notified because of the expected hypotension with reperfusion. The retroperitoneum should be closed in layers to adequately omit the graft from the GI tract. If unable to sufficiently close the retroperitoneum, then an omental flap should be created.[17][21][16][25]

The end-to-end anastomosis is preferred because it allows the graft to lie flatter and thus may lessen the chance of future aortoenteric fistula. This method also better allows for retrograde perfusion into the inferior mesenteric artery. However, in cases where there is bilateral external iliac artery occlusion, an end-to-side or formal reconstruction of one of the IIA is needed to ensure blood flow delivery to the pelvis.

There are also laparoscopic approaches, but this is not a widely utilized technique at this point.[21] There also is a relatively new technique called the EndoVascular RetroperitoneoScopic Technique (EVREST), which is a sutureless and clampless technique used during laparoscopic, retroperitoneal aortobifemoral bypass surgery.[26][27]

Complications

As with any surgical procedure, there exists a risk of bleeding or infection. In addition, there is a risk of wound infection, hematoma. Complications that result in significant morbidities include MI, renal dysfunction, and respiratory dysfunction. Late complications include hernias, graft thrombosis, and graft pseudoaneurysms, graft infections, aortoenteric fistulas further discussed below.

Most frequently, (in 50% of cases), cardiac ischemia is responsible for death related to aortic reconstruction, which is because there are seldom patients with normal coronary arteries. Hence the importance of pre-operative screening and treatment and cardiac co-morbidities. Mortality related to cardiac death following surgical intervention is 1% to 2.5% in some centers.[19]

Another common complication following surgery is renal insufficiency. This condition is typically a result of prolonged ischemia after clamping suprarenal, embolization secondary to clamping, hypoperfusion, hypovolemia or intrinsic renal artery disease. Often, this post-operative complication directly relates to the patient's preoperative cardiac and renal function. Knowing your patient's anatomy and having a precise plan preoperatively for clamping help reduce the incidence of renal insufficiency in the perioperative period.[19]

Graft limb thrombosis happens in up to 30% of patients following aortobifemoral bypass. A higher incidence occurs with younger patients, female gender, and extra-anatomic bypasses and those who failed to quit smoking post-operatively. Typically this is unilateral limb thrombosis, which most often occurs due to continuous intimal hyperplasia or outflow disease.[28]

An anastomotic pseudoaneurysm occurs in 1% to 5% of cases as a late complication.[29][30]ypically pseudoaneurysms arise secondary to a weakening near the suture line and maybe a sterile process or the product of infection. The most common site is at the femoral anastomosis. Typically, symptoms include a slowly enlarging bulge in the groin or are discovered incidentally on imaging. If an infection is an underlying cause, the most common causative organism is the Staphylococcus species. Graft infection is associated with high morbidity and mortality.[31] Repair is the usual recommendation if larger than 2 cm, if aortic pseudoaneurysm is greater than 50% of graft diameter, or if the graft is infected.[29][30] If the graft is infected, excision is usually indicated.

Aortoenteric fistula is a relatively rare occurrence but tends to be devastating and lethal if it occurs.[32] Mortality is at least 30% in most cases.[33] Typically it occurs secondary to an erosion of the proximal suture line on the aorta through the 3rd or 4th portion in the duodenum. It is often difficult to diagnosis because the triad of sepsis, abdominal pain, and GI bleeding are not always present. There may be a smaller, self-limited "herald-bleed" that occurs before any massive GI bleeding. CT scan with IV contrast and upper endoscopy are sometimes helpful in diagnosis. An important part of the patient's history will include the history of aortic surgery with graft placement. When found, emergency exploratory laparotomy is necessary with graft excision, debridement of infected tissue, bowel repair/resection, and extra-anatomic bypass or new graft placement. Even if surgery is successful, there is still high mortality associated with this complication.[32][33][34]

Clinical Significance

There is high post-procedure revascularization in most cases with 5-year patency typically ranging from 64 to 95%.[4]

Eighty percent of aortobifemoral bypass surgeries are successful and open the artery and relieve symptoms for approximately 10 years after the procedure. Pain is usually relieved when the patient is resting and greatly reduced when walking. The outlook is improved if the patient quits smoking prior to and after the bypass surgery. [35][3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Multi-faceted approach with vascular trained physicians who are both skilled in minimally invasive procedures and open procedures would undoubtedly enhance the outcome of these patients. Also, appropriate pre-operative workup with physician evaluation from other specialties can also be necessary for improving patient outcomes in populations with co-morbid conditions (particularly, other cardiac, renal, or pulmonary co-morbidities). Radiologists with experience in reading vascular studies are also crucial for helping to determine the extent of disease accurately. Anesthesia is essential intraoperatively for monitoring of blood pressure and treatment of reperfusion hypotension. Specialty-trained nurses play a vital role in post-operative management and monitoring of the patient's hemodynamic status and urine output. They should assist the interprofessional team in coordination of care, patient and family education, and monitoring of the patient's progress; reporting any untoward changes in the patient's condition to the team. All these disciplines need to collaborate to guide cases to optimal outcomes. [Level V]

The TASC II (Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease) recommends that patients be evaluated to undergo endovascular intervention first, if able (Level of Evidence B, Level III). Type A & B lesions in TASC classification are recommended to undergo endovascular therapy (Level of Evidence C, Level V). Whereas low-risk Type D lesions and low-risk surgical patients with Type C lesions are recommended to undergo surgical intervention (Level of Evidence C, Level V).[11]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brown KN,Gonzalez L, Leriche Syndrome 2019 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30855836]

Chiu KW,Davies RS,Nightingale PG,Bradbury AW,Adam DJ, Review of direct anatomical open surgical management of atherosclerotic aorto-iliac occlusive disease. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2010 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 20303805]

Sharma G,Scully RE,Shah SK,Madenci AL,Arnaoutakis DJ,Menard MT,Ozaki CK,Belkin M, Thirty-year trends in aortofemoral bypass for aortoiliac occlusive disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2018 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 30001912]

de Vries SO,Hunink MG, Results of aortic bifurcation grafts for aortoiliac occlusive disease: a meta-analysis. Journal of vascular surgery. 1997 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 9357455]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMah� G,Kaladji A,Le Faucheur A,Jaquinandi V, Internal Iliac Artery Disease Management: Still Absent in the Update to TASC II (Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease). Journal of endovascular therapy : an official journal of the International Society of Endovascular Specialists. 2016 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 26763263]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWressnegger A,Kinstner C,Funovics M, Treatment of the aorto-iliac segment in complex lower extremity arterial occlusive disease. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2015 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 25475917]

Ahmed S,Raman SP,Fishman EK, CT angiography and 3D imaging in aortoiliac occlusive disease: collateral pathways in Leriche syndrome. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2017 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 28401281]

Pokharel Y,Jones PG,Graham G,Collins T,Regensteiner JG,Murphy TP,Cohen D,Spertus JA,Smolderen K, Racial Heterogeneity in Treatment Effects in Peripheral Artery Disease: Insights From the CLEVER Trial (Claudication: Exercise Versus Endoluminal Revascularization). Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2018 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 29643064]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceManagement of peripheral arterial disease (PAD). TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC). Section D: chronic critical limb ischaemia. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2000 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 10957907]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRatnam L,Raza SA,Horton A,Taylor J,Markose G,Munneke G,Morgan R,Belli AM, Outcome of aortoiliac, femoropopliteal and infrapopliteal endovascular interventions in lesions categorised by TASC classification. Clinical radiology. 2012 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 22947210]

Norgren L,Hiatt WR,Dormandy JA,Nehler MR,Harris KA,Fowkes FG,TASC II Working Group., Inter-Society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease (TASC II). Journal of vascular surgery. 2007 Jan [PubMed PMID: 17223489]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBosiers M,Deloose K,Callaert J,Maene L,Beelen R,Keirse K,Verbist J,Peeters P,Schro� H,Lauwers G,Lansink W,Vanslembroeck K,D'archambeau O,Hendriks J,Lauwers P,Vermassen F,Randon C,Van Herzeele I,De Ryck F,De Letter J,Lanckneus M,Van Betsbrugge M,Thomas B,Deleersnijder R,Vandekerkhof J,Baeyens I,Berghmans T,Buttiens J,Van Den Brande P,Debing E,Rabbia C,Ruffino A,Tealdi D,Nano G,Stegher S,Gasparini D,Piccoli G,Coppi G,Silingardi R,Cataldi V,Paroni G,Palazzo V,Stella A,Gargiulo M,Muccini N,Nessi F,Ferrero E,Pratesi C,Fargion A,Chiesa R,Marone E,Bertoglio L,Cremonesi A,Dozza L,Galzerano G,De Donato G,Setacci C, BRAVISSIMO: 12-month results from a large scale prospective trial. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2013 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 23558659]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIndes JE,Mandawat A,Tuggle CT,Muhs B,Sosa JA, Endovascular procedures for aorto-iliac occlusive disease are associated with superior short-term clinical and economic outcomes compared with open surgery in the inpatient population. Journal of vascular surgery. 2010 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 20691560]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBath J,Rahimi M,Leite JO,Pierre-Louis W,Giglia J, Laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass in a United States academic center. The Journal of cardiovascular surgery. 2018 Nov 7; [PubMed PMID: 30417632]

Kogel HC, J�rg-Friedrich Vollmar, M.D., Professor em. of Surgery, University Ulm, mastery in vascular surgery. Langenbeck's archives of surgery. 2010 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 20213462]

Obitsu Y,Shigematsu H, [Revascularization for the aortoiliac regions of peripheral arterial disease]. Nihon Geka Gakkai zasshi. 2010 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 20387585]

Bajardi G,Ricevuto G,Grassi N,Latteri M, [Proximal anastomosis in aorto-bifemoral bypass. Technical considerations]. Minerva chirurgica. 1989 May 15; [PubMed PMID: 2761737]

Kelley-Patteson C,Ammar AD,Kelley H, Should the Cell Saver Autotransfusion Device be used routinely in all infrarenal abdominal aortic bypass operations? Journal of vascular surgery. 1993 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 8350435]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHertzer NR,Bena JF,Karafa MT, A personal experience with direct reconstruction and extra-anatomic bypass for aortoiliofemoral occlusive disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2007 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 17321340]

Hodgkiss-Harlow KD,Bandyk DF, Antibiotic therapy of aortic graft infection: treatment and prevention recommendations. Seminars in vascular surgery. 2011 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 22230673]

Guo LR, Gu YQ, Qi LX, Tong Z, Wu X, Guo JM, Zhang J, Wang ZG. Totally laparoscopic bypass surgery for aortoiliac occlusive disease in China. Chinese medical journal. 2013 Aug:126(16):3069-72 [PubMed PMID: 23981614]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceManny J,Romanoff H,Hyam E,Manny N, Monitoring of intraoperative heparinization in vascular surgery. Surgery. 1976 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 982283]

Tremey B,Szekely B,Schlumberger S,Fran�ois D,Liu N,Sievert K,Fischler M, Anticoagulation monitoring during vascular surgery: accuracy of the Hemochron low range activated clotting time (ACT-LR). British journal of anaesthesia. 2006 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 16873382]

Martin P,Greenstein D,Gupta NK,Walker DR,Kester RC, Systemic heparinization during peripheral vascular surgery: thromboelastographic, activated coagulation time, and heparin titration monitoring. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 1994 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 8204807]

Clair DG, Beach JM. Strategies for managing aortoiliac occlusions: access, treatment and outcomes. Expert review of cardiovascular therapy. 2015 May:13(5):551-63. doi: 10.1586/14779072.2015.1036741. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25907618]

Segers B,Horn D,Bazi MO,Lemaitre J,Van Den Broeck V,Stevens E,Roman A,Bosschaerts T, New development for aorto bifemoral bypass--a clampless and sutureless endovascular and laparoscopic technique. Vascular. 2014 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 23508384]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSegers B,Horn D,Lemaitre J,Roman A,Stevens E,Van Den Broeck V,Hizette P,Bosschaerts T, Preliminary results from a prospective study of laparoscopic aortobifemoral bypass using a clampless and sutureless aortic anastomotic technique. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2014 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 25065340]

Nevelsteen A,Suy R, Graft occlusion following aortofemoral Dacron bypass. Annals of vascular surgery. 1991 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 1825467]

Hagino RT,Taylor SM,Fujitani RM,Mills JL, Proximal anastomotic failure following infrarenal aortic reconstruction: late development of true aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, and occlusive disease. Annals of vascular surgery. 1993 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 8518123]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGhansah JN,Murphy JT, Complications of major aortic and lower extremity vascular surgery. Seminars in cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia. 2004 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 15583793]

O'Connor S,Andrew P,Batt M,Becquemin JP, A systematic review and meta-analysis of treatments for aortic graft infection. Journal of vascular surgery. 2006 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 16828424]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceArmstrong PA,Back MR,Wilson JS,Shames ML,Johnson BL,Bandyk DF, Improved outcomes in the recent management of secondary aortoenteric fistula. Journal of vascular surgery. 2005 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 16242551]

Marolt U,Potrc S,Bergauer A,Arslani N,Papes D, Aortoduodenal fistula three years after aortobifemoral bypass: case report and literature review. Acta clinica Croatica. 2013 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 24558769]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLimani K,Place B,Philippart P,Dubail D, Aortoduodenal fistula following aortobifemoral bypass. Acta chirurgica Belgica. 2005 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 15906917]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmato L,Fusco D,Acampora A,Bontempi K,Rosa AC,Colais P,Cruciani F,D'Ovidio M,Mataloni F,Minozzi S,Mitrova Z,Pinnarelli L,Saulle R,Soldati S,Sorge C,Vecchi S,Ventura M,Davoli M, Volume and health outcomes: evidence from systematic reviews and from evaluation of Italian hospital data. Epidemiologia e prevenzione. 2017 Sep-Dec [PubMed PMID: 29205995]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence