Introduction

Undifferentiated patients often present with conditions that may be due to drug exposure and may require specialized diagnostic testing. Patients may present due to unintentional poisoning, attempts at self-harm, or environmental exposures. These patients will predominantly present to the emergency department For the scope of this article, the acutely ill patient requiring screening will be the focus, rather than workplace drug screens and mandated or routine testing performed in rehabilitation programs. Screening tests for exposures and drugs of abuse can vary in availability, accuracy, and utility. Knowledge of the limitations and clinical applicability of toxicologic screening is necessary to order and interpret these studies properly.[1][2][3]

Etiology and Epidemiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology and Epidemiology

A significant number of acute care visits to medical providers are associated with the presence of drug exposures based purely on history. Alcohol intoxication has long been and remains the most common reason for a substance-related patient visit. However, there are rising rates of opioids, cocaine, marijuana, and synthetic drug-related visits over the past 30 years. Fifty-one percent of drug-related emergency department visits in the United States involved illicit drug use, with co-ingestions being common, 25% of which involved co-ingestion with alcohol. 8% of visits were drug-related suicide attempts and the majority of these involved over-the-counter or prescription medications. Accidental ingestions accounted for 4% of all visits and were primarily pediatric exposures. The highest rates of drug-related visits occurred among patients between the ages of 18 and 35.

Specimen Requirements and Procedure

In the setting of acute illness, serum and urine samples are acquired for laboratory testing without specific concern for drug screening. Urine specimen requirements for screening do exist, mostly in the context of mandated or routine testing. Typically a collection of the specimen should occur within 4 minutes of providing a sample and with a volume of at least 30 mL. The urine temperature should be between 32.2 C (90 F) and 37.7 C (100 F) with a pH of 4.5 to 8.5. These requirements are essentially an attempt to ensure the sample is from the individual providing it and without added diluents or substances that might interfere with testing.

Diagnostic Tests

Toxicology screens have changed markedly over the years. Methods such as gas chromatography and radioimmunoassays have given way in everyday use to enzyme-linked sorbent immunoassay (ELISA) and cloned enzyme donor immunoassay (CEDIA). This migration is largely due to speed and ease of use. However, these new generation immunoassays carry with them limitations in the form of reduced sensitivity and specificity. The calibration of these tests can detect specific substances rather than an entire class of drugs and also suffer from cross-reactivity to structurally similar compounds. Comprehensive drug screens utilizing other methods tend to be prohibitive in terms of expense and typically can take weeks to result, making them impractical for clinical use.[4][5][6]

Drug testing is possible using samples from urine, serum, breath, sweat, or saliva. Breath testing is used nearly entirely on estimating alcohol concentrations, and urine and serum tests remain the most commonly used for medical professionals.

Urine Testing

Illicit drugs of abuse are a common area of interest in screening and utilize urine testing. Five drugs commonly tested in the United States in a urine screen are:

- Cocaine

- Amphetamines

- Marijuana

- Phencyclidine (PCP)

- Opioids

These drugs were targeted for drug screening by the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Many assays include benzodiazepines as well. In addition to issues with false positives or negatives of the test, the standard urine assay will not screen for some existing illicit drugs. The epidemiology of drug use has shifted over the past ten years, and there is a higher prevalence of substances such as synthetic cannabinoid, MDMA (ecstasy), and chemical variants of opioids and PCP, which may not be detected by many urine screens. Other drugs of misuse that are generally unscreened include ketamine, chloral hydrate, gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), psilocybin, and bath salts (cathinones).[7][8]

Most urine drug screens do not provide quantitative testing, so a simple “positive” or “negative” result is given if the assay detects substrate.

Serum Testing

Serum tests screen for common over-the-counter drugs which are likely sources for intended overdoses. These tests commonly obtain acetaminophen, aspirin, salicylates, and ethanol. Some extended serum screens include tricyclic antidepressants or barbiturates. Unlike urine screens, these tests are often quantitative and are useful in measuring blood concentrations. Concentrations require interpretation as to the reported times and amounts of ingestion, and often serial concentrations are necessary when the history is lacking or unreliable. While ethanol is detectable in the alcohol screen, other toxic alcohols like methanol, ethylene glycol, and isopropyl alcohol are not detectable.[9]

Testing Procedures

For the clinician ordering toxicologic screening, there are a few considerations. One is to order screening for clinical purposes only unless the patient requests specific testing for legal consideration. This request might include a suspected sexual abuse patient seeking a drug screen. Because the performance of this test is a duty to the patient, it is permitted. Testing performed at the request of other parties (including law enforcement), or to benefit other parties (including other patients) is not permissible without the patient’s consent. In cases where the patient is unable to consent (a common occurrence with suspected drug use), the clinician utilizes testing as a diagnostic tool, again, for the benefit of the patient.

There are a few circumstances when there can be screening, even when not in the service of the patient. If officials present a valid warrant, testing is permissible when not clinically relevant. If there is a legitimate public safety concern, then the physician may order and reveal test results if performed “in good faith.” This decision may be open to the scrutiny of a judge to determine, and so clinicians are left to act on their best judgment, to prevent harm to their patients or others.[10]

Results, Reporting, and Critical Findings

Urine tests are qualitative and detect the presence of multiple illicit drugs. Various drugs are detectable in the urine for varying amounts of time, and these results require careful interpretation and clinical correlation. Some substances or their metabolites may be present and result in true positives but are detected far beyond the time they would be clinically relevant. Urine screens may result in positives for a prolonged period after use or clinical effect.

- Cocaine: The test detects the metabolite benzoylecgonine quite accurately with not much concern for false positives or negatives, but the metabolite may be present up to 3 days after use while having most clinical effects within 6 to 12 hours of use.

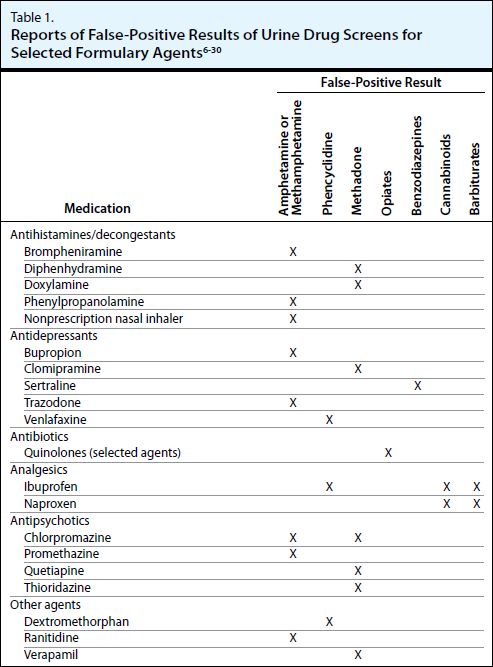

- Amphetamines: Many false positives to amphetamines exist, including antihistamines, decongestants, antidepressants, or acid-blockers, and may be detected 1 to 3 days after use.

- Marijuana: Common over-the-counter analgesics like ibuprofen and naproxen can cross-react with this assay, creating false positives.

- Phencyclidine (PCP): False positives exist, notably with ibuprofen, dextromethorphan, and tramadol, and the time for detection can last 1 to 2 weeks after use.

- Opioids: Many opioids can be missed on routine screening, generating significant false negatives, and there are reports of false-positive results in the presence of poppy seeds and quinolone antimicrobials. Opioids are detectable for 1 to 4 days after use.

- Benzodiazepines: These results are likely among the least clinically useful screens. A few false positives exist, but false negatives are far more common, as most assays detect the specific metabolite oxazepam, while multiple benzodiazepines with unique metabolites are likely to be missed. Diazepam is metabolized to oxazepam and would be identified, but might be present for up to 4 weeks after use. On the other hand, midazolam, lorazepam, and alprazolam all metabolize into other substances and therefore, would remain undetected.

Serum testing may be more open to the interpretation of timing due to quantitative testing, but it can be unclear if concentrations are rising or falling, and pharmacokinetics and metabolism of substances can be very difficult to predict, necessitating repeat sampling.

Some issues with false positives and negatives have been addressed above, but there is no exhaustive list of cross-reactants. The table below is reproduced with permission, drawing on several reviews of common pitfalls of drug screens.[11]

Clinical Significance

The use of toxicologic screening can help to guide acute management or chronic treatment. But both urine and serum tests carry significant caveats that limit their clinical utility.

Positive drug screens in patients without clinical symptoms may reflect the detection of metabolites and previous use, and not lead to any changes in management. They may also reflect acute use in patients who exhibit tolerance and, thus, minimal symptoms. Positive screens in patients with symptoms that do fit with acute intoxication may still reflect prior use and cause clinicians to assume, incorrectly, that there is a definitive diagnosis. Negative screens will often not be able to exclude the use of these substances as well.

While changes in clinical management are not very common with urine testing, serum toxicologic screens can occasionally be very clinically useful. Serum testing in patients with intentional ingestions is necessary to detect acetaminophen. An antidote to acetaminophen poisoning exists, i.e., N-acetyl-cysteine, and is most useful for early identification of these ingestions. Serum acetaminophen concentrations may be the only evidence of acute poisoning in patients with “stage 1” toxicity and minimal clinical signs or symptoms. Salicylate toxicity is another entity that can be a diagnostic challenge, and serum concentrations can help guide management.

Urine tests give qualitative, presumptive results and need clinical interpretation

Serum tests give quantitative, presumptive results and need clinical interpretation, in addition to potentially obtaining repeat sampling for certain poisonings.

All toxicologic screening must be interpreted within the context of the patient presentation and should not routinely be a procedure as either exclusionary or confirmatory in a suspected exposure.[12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Screening for toxic substances is now routine in most emergency departments. However, healthcare workers need to know that in many cases, the results of a toxicology screen are not immediately available, and clinical acumen is required. Toxicological screens take place for various reasons, including a forensic investigation, rape, use of illicit drugs, and drug overdose. While consent is recommended before such testing, some patients may not be able to provide consent for whatever reason. In such scenarios, as long as the clinician is acting in good faith for the benefit of the patient or a legal warrant, then testing can be done without consent.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Crouse JJ, Chitty KM, Iorfino F, White D, Nichles A, Zmicerevska N, Guastella AJ, Moustafa AA, Hermens DF, Scott EM, Hickie IB. Exploring associations between early substance use and longitudinal socio-occupational functioning in young people engaged in a mental health service. PloS one. 2019:14(1):e0210877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210877. Epub 2019 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 30653581]

Gessner A, König J, Fromm MF. Clinical Aspects of Transporter-Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2019 Jun:105(6):1386-1394. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1360. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30648735]

Sluiter RL, Janzing JGE, van der Wilt GJ, Kievit W, Teichert M. An economic model of the cost-utility of pre-emptive genetic testing to support pharmacotherapy in patients with major depression in primary care. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2019 Oct:19(5):480-489. doi: 10.1038/s41397-019-0070-8. Epub 2019 Jan 16 [PubMed PMID: 30647446]

Patlewicz G, Richard AM, Williams AJ, Grulke CM, Sams R, Lambert J, Noyes PD, DeVito MJ, Hines RN, Strynar M, Guiseppi-Elie A, Thomas RS. A Chemical Category-Based Prioritization Approach for Selecting 75 Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) for Tiered Toxicity and Toxicokinetic Testing. Environmental health perspectives. 2019 Jan:127(1):14501. doi: 10.1289/EHP4555. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30632786]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShahi S, Özcan M, Maleki Dizaj S, Sharifi S, Al-Haj Husain N, Eftekhari A, Ahmadian E. A review on potential toxicity of dental material and screening their biocompatibility. Toxicology mechanisms and methods. 2019 Jun:29(5):368-377. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2019.1566424. Epub 2019 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 30642212]

Thomas AA, Dickerson-Young T, Mazor S. Unintentional Pediatric Marijuana Exposures at a Tertiary Care Children's Hospital in Washington State: A Retrospective Review. Pediatric emergency care. 2021 Oct 1:37(10):e594-e598. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001703. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30601351]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWhite J, Weinstein SA, De Haro L, Bédry R, Schaper A, Rumack BH, Zilker T. Mushroom poisoning: A proposed new clinical classification. Toxicon : official journal of the International Society on Toxinology. 2019 Jan:157():53-65. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.11.007. Epub 2018 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 30439442]

Nakhaee S, Naseri K, Mehrpour O. Toxic alcohol diagnosis and management: an emergency medicine review-comment. Internal and emergency medicine. 2019 Oct:14(7):1183-1184. doi: 10.1007/s11739-018-02012-0. Epub 2019 Jan 1 [PubMed PMID: 30600525]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePosin SL, Kong EL, Sharma S. Mercury Toxicity. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29763110]

Farley TM, Anderson EN, Feller JN. False-positive phencyclidine (PCP) on urine drug screen attributed to desvenlafaxine (Pristiq) use. BMJ case reports. 2017 Nov 23:2017():. pii: bcr-2017-222106. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222106. Epub 2017 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 29170178]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKling J. Toxicology testing steps towards computers. Lab animal. 2019 Feb:48(2):40-42. doi: 10.1038/s41684-018-0227-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30643278]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrent J. Fomepizole for ethylene glycol and methanol poisoning. The New England journal of medicine. 2009 May 21:360(21):2216-23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0806112. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19458366]