Introduction

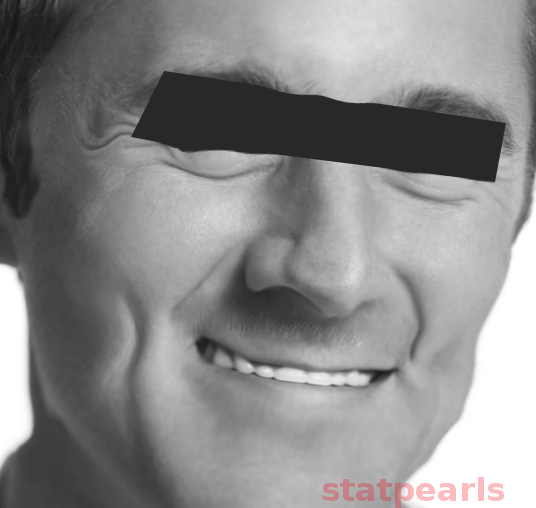

HIV-associated lipodystrophy is an undesirable effect of antiretroviral therapy (ART) that occurs due to the redistribution of adipose tissue (see Image. HIV-Induced Lipodystrophy). The first reports of this condition were in 1997 among people taking ART. HIV-associated lipodystrophy can manifest as two distinct phenotypes: fat accumulation (lipohypertrophy) or fat loss (lipoatrophy). In some patients, the 2 manifestations may coexist as well.

Lipoatrophy occurs on the face, buttocks, arms, and legs. In contrast, lipohypertrophy occurs in the truncal areas and manifests as abdominal obesity, mammary hypertrophy, accumulation of fat on the neck, or lipomas. These body image and habitus changes, especially facial lipoatrophy, have been linked to depression, decreased self-esteem, sexual dysfunction, and social isolation and can greatly affect the patient’s quality of life and adherence to ART.[1][2] Lipodystrophy also contributes to morbidity via the development of insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and endothelial dysfunction, which can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease. Therefore, identification and prompt management of HIV-associated lipodystrophy are of utmost importance.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The exact cause of lipodystrophy is unknown. However, using specific thymidine analog nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI), such as zidovudine and stavudine, is associated with developing lipoatrophy. Switching to newer agents, such as abacavir or tenofovir, has been shown to prevent the progression of this disease. In contrast, although lipohypertrophy sometimes occurs with protease inhibitors (PI), switching or discontinuing PI has not been shown to reverse fat accumulation.[4][5] Given the two distinct phenotypes of this disease, it is useful to separate the two manifestations to help understand etiological factors.

Lipoatrophy

As stated above, the leading risk factor for lipoatrophy is using NRTIs. The drugs that are most notorious for causing lipoatrophy include stavudine and zidovudine. An open-label randomized controlled trial comparing abacavir or stavudine, with each group receiving additional antiretroviral therapy with lamivudine and efavirenz, reported 38% incidence of lipoatrophy in the stavudine group versus 5% incidence in abacavir group.[6] Another study comparing stavudine to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, with each group receiving additional antiretroviral therapy with lamivudine and efavirenz, reported no evidence of lipoatrophy in patients taking tenofovir at 144 weeks, whereas 50% of the patients taking stavudine developed lower limb fat mass during the same period.[7]

Other antiretroviral classes have also been implicated in the risk of this disease; however, the evidence is less clear as most of these studies had concurrent use of NRTIs. There is some evidence to suggest that the use of culprit NRTI with a protease inhibitor may have a synergistic effect on lipoatrophy.[8] It is clear, however, that protease inhibitors alone do not cause lipoatrophy.[4] Other factors associated with an increased risk of lipoatrophy include increased age, coinfection with hepatitis C, higher HIV viral loads, and lower CD4 cell counts at the time of initiation of HIV therapy.[9][10]

Lipohypertrophy

In contrast to lipoatrophy, the risk factors for fat accumulation tend to be host factors. These include advanced age, female gender, and higher body fat percentage at baseline.[11] In addition, host lifestyle factors, such as high caloric intake with resultant elevated baseline triglyceride levels, have also been implicated as a risk factor for lipohypertrophy in patients with HIV.[12] In contrast, a high-fiber, high-protein diet may help prevent fat deposition and accumulation.[13]

There is no evidence to suggest specific antiretroviral agents lead to fat accumulation. However, fat accumulation, specifically central adiposity, has been associated with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Although PI therapy was initially thought to cause lipohypertrophy, randomized controlled trials that substituted PI with alternative ART (eg, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors [NNRTIs] or integrase inhibitors) in patients with lipodystrophy did not result in a decrease in visceral fat. Therefore, studies have not been able to definitively report an association between ART, especially PI, and fat accumulation in HIV-infected individuals.[14]

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of HIV-associated lipodystrophy has been challenging to establish due to differences in case definition, but estimates range from 10% to 80% among all people living with HIV worldwide.[15] The newer HIV medicines are thought to be less likely to cause lipodystrophy than the previously used agents.

A 2005 study evaluating 452 patients reported a baseline prevalence of 35% for fat atrophy, 44% for fat accumulation (central adiposity), and 14% for a combination of the two syndromes in patients living with HIV.[11] Moreover, this study noted a change in the prevalence of these syndromes over time. After a 1-year follow-up, 22% developed new lipoatrophy, while 16% of the patients who previously had it did not. Similarly, 23% of the patients developed new fat deposition syndromes, whereas 15% of those with fat deposition at baseline did not have it at 1-year follow-up.[11]

Pathophysiology

The underlying mechanisms associated with HIV-associated lipodystrophy involve changes induced by HIV infection itself and metabolic changes triggered by certain classes of antiretroviral drugs. HIV-1 virus infection per se results in a proinflammatory change in adipose tissue, which can contribute to lipodystrophy and subsequent metabolic abnormalities. It stimulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-alfa, IL-6, and IL-1beta), which induce a stress response in adipocytes, leading to physical cell damage. TNF-alfa mediates insulin resistance by reducing insulin receptor kinase activity, which triggers apoptosis and lipolysis. It also downregulates the insulin receptor kinase substrate (IRS-10) and GLUT-4 transporter. Inflammation contributes to insulin resistance through impaired adipocyte metabolism and lipolysis.[16]

The mechanisms by which antiretroviral drugs play a role in developing lipodystrophy are incompletely understood. Protease inhibitors (PIs) and reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) have been shown to disrupt adipocyte function and lipid and glucose metabolism. These drugs reduce adipocyte differentiation and adiponectin's expression, secretion, and release from adipose tissue. Adiponectin is a key player in glucose regulation and fatty acid oxidation. Antiretroviral drugs increase lipolysis and suppress lipogenesis, decreasing free fatty acids (FFA) uptake by adipocytes and increasing the release of stored triglycerides and glycerol in the bloodstream.[17] Mitochondrial toxicity induced by NRTIs also plays a role in the development of the syndrome. This drug class inhibits mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma, stimulating catabolic activity by dysregulating the production and synthesis of hormones and cytokines.

Mitochondrial toxicity, insulin resistance, and genetics are also thought to be some of the additional pathophysiological mechanisms related to the development of HIV-associated lipodystrophy. Lipoatrophy correlates with severe mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation. Lipohypertrophy is linked to mild mitochondrial dysfunction and cortisol activation stimulated by inflammation. Further, lipoatrophy in the lower part of the body and lipohypertrophy in the abdomen carries associations with metabolic changes similar to metabolic syndrome, especially dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance.[16]

There also appears to be a genetic component to the pathophysiology of this disease. In treatment-naive patients, for example, the development of lipodystrophy and metabolic changes on antiretroviral therapy was linked to a single nucleotide polymorphism in the resistin gene.[18] Similarly, genetic polymorphisms involved in apoptosis have been linked to lipoatrophy.[19] Recent studies have also identified the dysregulation of microRNAs as a crucial factor in causing adipose dysfunction in patients with HIV.[20]

History and Physical

History must include detailed information describing patient and clinician-reported changes in physical appearance associated with antiretroviral agents. Information about specific antiretroviral medications and medicines used to treat comorbid conditions is necessary. The length of treatment with each ART combination, including PIs, NRTIs, NNRTIs, and integrase inhibitors, is needed data. A personal and family history assessment for metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease should also be a requirement. A social history should include diet, exercise regimen, smoking, alcohol consumption, and illicit drug use. Patients may report sleep difficulties due to neck enlargement. Patients should undergo evaluation for anxiety, depression, and a loss of self-esteem depression, as well as compliance with ART. It is well known that lipodystrophy can cause patients to be non-compliant with ART.

A physical exam should include body mass index, waist circumference, blood pressure, and clinical signs of lipodystrophy. The clinician should evaluate for features of lipoatrophy as manifested by loss of peripheral fat tissue in the upper and lower extremities and buttocks as well as malar and temporal areas. Extremities may appear thin with the prominence of superficial veins, and loss of facial fat causes sunken eyes and cachectic facial features.[1] Patients with lipohypertrophy show an accumulation of fat tissue in certain areas. For example, central lipohypertrophy is characterized as intra-abdominal fat accumulation manifested by abdominal protuberance. Fat deposition can present in the dorsocervical area (buffalo hump), breast enlargement in both men and women and the anterior neck and mandibular area. Lipomas can also be a feature.

Clinical Features of Lipoatrophy

Lipoatrophy presents as loss of subcutaneous fat in the face, arms, legs, abdomen, or buttocks.[11] This is a preferential loss of fat without any evidence of muscle atrophy, which helps distinguish it from AIDS-associated wasting.[21] Facial lipoatrophy presents with buccal and temporal fat pad loss, concave cheeks, periorbital hollowing, and visible facial musculature.[22]

Lipoatrophy in the extremities presents with a prominence of veins and musculature, while central lipoatrophy presents with loss of subcutaneous fat in the abdomen.[21] Evaluating subcutaneous abdominal fat in patients with lipoatrophy can also help identify patients with coexisting central fat deposition. In patients where the two syndromes coexist, there will be scant "pinchable" abdominal fat due to subcutaneous fat atrophy; however, there will be a high waist circumference due to increased intraabdominal fat.[23]

Clinical Features of Lipohypertrophy

The hallmark features of this phenotype include central adipose tissue deposition with increased abdominal girth and a "buffalo hump" in the dorsocervical area. However, these features are difficult to distinguish from general obesity. The lack of subcutaneous fat helps distinguish this syndrome from obesity.[23] This fat deposition may also occur in liver tissue and muscles over time.

Evaluation

All patients on ART should be monitored for the development of lipodystrophy, which can be performed by measuring abdominal girth, hip, and mid-upper arm circumferences. Monitoring body weight and body mass index is of the utmost importance for identification, and early intervention is likely more effective than reversing fat accumulation.

The diagnosis of HIV-associated lipodystrophy is based on the patient's characteristic physical appearance. Due to the increased incidence of metabolic abnormalities in patients with HIV-associated lipodystrophy, lipid profile, and glucose tolerance should be evaluated, ideally before the initiation of antiretroviral therapy, and repeated every six months. Hemoglobin A1c may be useful; however, it may underestimate hyperglycemia due to increased red blood cell turnover in HIV infection. Liver and kidney function tests are necessary at regular intervals as well.

Objective fat accumulation or loss evaluation can be obtained by radiographic imaging such as computed tomography, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, or magnetic resonance imaging; however, they are not more sensitive than patient self-report and physical examinations, especially given the added cost of these tests.[4] Anthropometric measurements are more useful in assessing and monitoring patients with lipodystrophy, although the interobserver differences in measurements may make them less reliable.

Evaluation and Monitoring

The recommended evaluation and monitoring strategies for HIV-associated lipodystrophy include:

- Waist Measurement

- An abdominal circumference greater than 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women is considered abnormal and should warrant further evaluation for fat accumulation.

- Serial weight and body mass index (BMI) measurements

- This is particularly helpful when compared to an increased waist circumference.

- Routine fasting lipid profile

- Routine testing for glucose metabolism

Treatment / Management

Treatment for HIV-associated lipodystrophy depends on the phenotypic profile of the patient.

Treatment of HIV-associated Lipoatrophy

The most important treatment strategy in patients with this disease is to switch the antiretroviral therapy combination to exclude the use of stavudine and zidovudine. Alternate NRTIs that may be used include tenofovir or abacavir. Multiple clinical trials have shown improvement in lipoatrophy with this treatment strategy.[5][25] An alternative to NRTI-based regimens is a protease inhibitor-containing, nucleoside-sparing regimen. Support for this therapy comes from a clinical trial evaluating patients with advanced HIV who were switched either to a regimen containing lopinavir/ritonavir and efavirenz or two nucleoside analogs and efavirenz.[26] At a 48-week follow-up, the study reported a significant increase in limb fat in the nucleoside-sparing group; however, it also reported an increase in serum triglycerides and total cholesterol levels. Careful evaluation of the patient’s underlying comorbidities, such as hepatitis B and resistance profile, should be taken into consideration when making a switch in ART therapy to prevent any untoward complications.(A1)

Regimen changes that have not shown any clinical benefit in treating lipoatrophy include switching from a protease inhibitor to an NNRTI or an older-generation protease inhibitor to a newer agent in the same class.[27][28] Thiazolidinediones are another possible treatment that can be considered for patients with lipoatrophy. However, their use has not proven beneficial and remains investigational. In patients who do not improve with ART regimen alterations and need treatment for lipoatrophy, a trial of pioglitazone can be considered if they have evidence of insulin resistance.[29] In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, pioglitazone was shown to increase limb fat at 48 weeks.[30] The clinical benefit was not perceived by the patients in this trial. However, the study did report improved lipid profiles with this treatment.(A1)

It is important to note that regimen changes may favorably affect limb lipoatrophy but have minimal effect on facial lipoatrophy. Plastic surgery is the mainstay of therapy for patients affected with facial lipoatrophy, which may require injectable gel fillers or autologous fat transplantation.[31][32](A1)

Although uridine supplementation can theoretically protect patients from lipoatrophy while on thymidine analogs, a multicenter clinical trial found uridine supplementation ineffective after 48 weeks of treatment compared to a placebo.[33](B3)

Treatment of HIV-associated Lipohypertrophy

The mainstay of therapy for patients with this syndrome is lifestyle modifications with diet and exercise.[34] If patients have concomitant glucose intolerance or diabetes, metformin can be added, which may also benefit fat deposition.[35] Counseling regarding the importance of smoking cessation, dietary modifications, and regular exercise is essential and is similar to that of healthy patients. Dietary counseling should focus on reducing the intake of saturated fats and cholesterol and increasing the consumption of vegetables, protein, and fiber-containing foods. Cardiovascular and strength training can reduce visceral adiposity and improve muscle strength, lean body mass, and lipid levels.(A1)

In severe cases, who do not respond to conservative treatment, tesamorelin can be considered. This is a growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) analog that can be used to treat excess abdominal fat. Although the efficacy of this therapy in reducing abdominal fat deposition is established, long-term safety data is still lacking; therefore, prolonged treatment should be pursued with extreme caution.[36] The beneficial effects on central adiposity wane when therapy is discontinued, further limiting its use.[37] (A1)

Surgical management of lipohypertrophy includes liposuction and lipectomy. However, the duration of the effect is variable, and recurrence is common, which renders these options less favorable.[38][39][40]

Medical Treatment of Dyslipidemia

Lipid-decreasing therapy can be considered when low-density lipoprotein levels are high. In such cases, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors (statins) would be preferred; however, caution is advised given the risk of side effects with concomitant ART therapy. Pravastatin, low-dose atorvastatin, or fluvastatin are recommended as first-line agents in patients receiving protease inhibitors, and dose adjustments may be needed to avoid the risk of statin toxicity.[4] When triglyceride elevations predominate, fibrate therapy can be considered as well. Ezetimibe use in patients with HIV is limited due to scant data supporting its tolerability with ART therapy. Bile acid sequestrants are contraindicated in these patients due to their effect on the absorption of antiretrovirals.[4]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for lipoatrophy includes:

- Malnutrition

- Hyperthyroidism

- AIDS-wasting syndrome

- Anorexia nervosa

- Cachexia

The differential diagnosis for lipohypertrophy includes:

- Cushing syndrome

- Glucocorticoid therapy

- Simple obesity

Prognosis

HIV-associated lipodystrophy progressively worsens when protease inhibitors and thymidine analog NRTI therapy continue. As these conditions develop, altering body image and self-esteem may lead to poor compliance with antiretroviral therapy and, ultimately, treatment failure.[4] Moreover, developing proatherogenic dyslipidemia and alteration of glucose metabolism is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in these patients.[4] Early identification and management of HIV-associated metabolic complications can halt the progression of these conditions and, in some cases, may help reverse lipodystrophy.[4][11]

Complications

HIV-associated lipodystrophy is known to cause significant psychological distress and correlates with depression, decreased self-esteem, and social isolation.[4] Patients may become non-compliant due to the fear of the development of lipodystrophy and concern that the presence of lipodystrophy may make the diagnosis of HIV obvious. Metabolic complications include hyperlipidemia and hyperglycemia due to insulin resistance, which increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.[4] Neck enlargement can lead to neck pain and sleep apnea. Further, increased abdominal girth due to increased visceral fat accumulation can cause symptoms of abdominal distention and gastroesophageal reflux.

Consultations

Consultations that are typically requested for patients with this condition include the following:

- An endocrinology consult is recommended for patients who are candidates for tesamorelin therapy.

- A plastic surgery consultation is recommended for patients interested in filler administration or removal of adipose tissue.

- A psychiatry or psychology consultation may be necessary for patients affected by undesired changes in body habitus.

- An infectious disease consult should take place when considering an antiretroviral therapy switch.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is instrumental in determining potential adverse events and the follow-up process when initiating antiretroviral therapy for patients.[4] Avoidance of antiretroviral agents associated with lipodystrophies, such as stavudine and zidovudine, can decrease the risk of this disease. Currently, stavudine or zidovudine are no longer considered first-line regimens for the treatment of HIV. Patients who are on these drugs should switch to other antiretroviral classes.

Prevention of fat accumulation relies on encouraging a healthy lifestyle among patients with HIV by encouraging exercise, high-fiber and high-protein diets, and monitoring weight.[4] A healthy lifestyle, including exercise and avoidance of unhealthy behaviors such as smoking, may also be similarly beneficial and should be encouraged in patients with HIV to mitigate the risk of long-term cardiovascular disease associated with lipodystrophy in these patients.[13]

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts to keep in mind about HIV-associated lipodystrophy are as follows:

- HIV-associated lipodystrophy characteristically presents as lipoatrophy, lipohypertrophy, or a combination of both in HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy.

- The syndrome can significantly impact an individual's quality of life, both physically and psychologically.

- Treatment regimens containing thymidine analog nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), such as stavudine and zidovudine, are most commonly associated with lipoatrophy and should be avoided.

- HIV-associated lipodystrophy can be accompanied by hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and hyperglycemia, contributing to morbidity.

- Management of lipodystrophy includes switching ART, lifestyle modifications, pharmacologic interventions, and surgical treatment.

- Because lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy are challenging to treat, prevention is essential and can be accomplished by avoiding agents associated with lipodystrophy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Recognizing and addressing HIV-associated lipodystrophy represents a challenge, given its multifactorial etiology and development over time. HIV infection and the use of specific antiretroviral agents are key factors in the development of the syndrome. Providers taking care of HIV-positive patients must closely follow glucose levels, lipid profile, and body habitus changes to detect metabolic changes secondary to antiretroviral drugs and make proper adjustments such as switching medications, adding hypoglycemic agents, or lipid-lowering drugs. Specialty nurses are key in educating patients about the potential side effects of ART and self-monitoring strategies to help identify these complications early. Pharmacists play a pivotal role in assisting clinicians in choosing an appropriate ART regimen and addressing dyslipidemia so that adverse drug effects and interactions are minimized. Consultation with a psychiatrist or mental health nurse is recommended for patients emotionally affected by body habitus and body image changes to help them cope with the treatment alterations so that treatment adherence is not affected and clinical complications are minimized. A well-coordinated interprofessional team can optimize clinical outcomes for patients with lipodystrophy.[41]

Media

References

Abel G, Thompson L. "I don't want to look like an AIDS victim": A New Zealand case study of facial lipoatrophy. Health & social care in the community. 2018 Jan:26(1):41-47. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12459. Epub 2017 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 28557181]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVerolet CM, Delhumeau-Cartier C, Sartori M, Toma S, Zawadynski S, Becker M, Bernasconi E, Trellu LT, Calmy A, LIPO Group Metabolism. Lipodystrophy among HIV-infected patients: a cross-sectional study on impact on quality of life and mental health disorders. AIDS research and therapy. 2015:12():21. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0061-z. Epub 2015 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 26097493]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBeraldo RA, Santos APD, Guimarães MP, Vassimon HS, Paula FJA, Machado DRL, Foss-Freitas MC, Navarro AM. Body fat redistribution and changes in lipid and glucose metabolism in people living with HIV/AIDS. Revista brasileira de epidemiologia = Brazilian journal of epidemiology. 2017 Jul-Sep:20(3):526-536. doi: 10.1590/1980-5497201700030014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29160443]

Wohl DA,McComsey G,Tebas P,Brown TT,Glesby MJ,Reeds D,Shikuma C,Mulligan K,Dube M,Wininger D,Huang J,Revuelta M,Currier J,Swindells S,Fichtenbaum C,Basar M,Tungsiripat M,Meyer W,Weihe J,Wanke C, Current concepts in the diagnosis and management of metabolic complications of HIV infection and its therapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 16886161]

Martin A, Smith DE, Carr A, Ringland C, Amin J, Emery S, Hoy J, Workman C, Doong N, Freund J, Cooper DA, Mitochondrial Toxicity Study Group. Reversibility of lipoatrophy in HIV-infected patients 2 years after switching from a thymidine analogue to abacavir: the MITOX Extension Study. AIDS (London, England). 2004 Apr 30:18(7):1029-36 [PubMed PMID: 15096806]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePodzamczer D, Ferrer E, Sanchez P, Gatell JM, Crespo M, Fisac C, Lonca M, Sanz J, Niubo J, Veloso S, Llibre JM, Barrufet P, Ribas MA, Merino E, Ribera E, Martínez-Lacasa J, Alonso C, Aranda M, Pulido F, Berenguer J, Delegido A, Pedreira JD, Lérida A, Rubio R, del Río L, ABCDE (Abacavir vs. d4T (stavudine) plus efavirenz) Study Team. Less lipoatrophy and better lipid profile with abacavir as compared to stavudine: 96-week results of a randomized study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2007 Feb 1:44(2):139-47 [PubMed PMID: 17106274]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGallant JE, DeJesus E, Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gazzard B, Campo RE, Lu B, McColl D, Chuck S, Enejosa J, Toole JJ, Cheng AK, Study 934 Group. Tenofovir DF, emtricitabine, and efavirenz vs. zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz for HIV. The New England journal of medicine. 2006 Jan 19:354(3):251-60 [PubMed PMID: 16421366]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDubé MP,Parker RA,Tebas P,Grinspoon SK,Zackin RA,Robbins GK,Roubenoff R,Shafer RW,Wininger DA,Meyer WA 3rd,Snyder SW,Mulligan K, Glucose metabolism, lipid, and body fat changes in antiretroviral-naive subjects randomized to nelfinavir or efavirenz plus dual nucleosides. AIDS (London, England). 2005 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 16227788]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMcDermott AY, Terrin N, Wanke C, Skinner S, Tchetgen E, Shevitz AH. CD4+ cell count, viral load, and highly active antiretroviral therapy use are independent predictors of body composition alterations in HIV-infected adults: a longitudinal study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005 Dec 1:41(11):1662-70 [PubMed PMID: 16267741]

Duong M, Petit JM, Piroth L, Grappin M, Buisson M, Chavanet P, Hillon P, Portier H. Association between insulin resistance and hepatitis C virus chronic infection in HIV-hepatitis C virus-coinfected patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2001 Jul 1:27(3):245-50 [PubMed PMID: 11464143]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJacobson DL, Knox T, Spiegelman D, Skinner S, Gorbach S, Wanke C. Prevalence of, evolution of, and risk factors for fat atrophy and fat deposition in a cohort of HIV-infected men and women. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2005 Jun 15:40(12):1837-45 [PubMed PMID: 15909274]

Hadigan C, Dietary habits and their association with metabolic abnormalities in human immunodeficiency virus-related lipodystrophy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2003; [PubMed PMID: 12942382]

Hendricks KM, Dong KR, Tang AM, Ding B, Spiegelman D, Woods MN, Wanke CA. High-fiber diet in HIV-positive men is associated with lower risk of developing fat deposition. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2003 Oct:78(4):790-5 [PubMed PMID: 14522738]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHeath KV, Hogg RS, Chan KJ, Harris M, Montessori V, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montanera JS. Lipodystrophy-associated morphological, cholesterol and triglyceride abnormalities in a population-based HIV/AIDS treatment database. AIDS (London, England). 2001 Jan 26:15(2):231-9 [PubMed PMID: 11216932]

Mallon PW, Miller J, Cooper DA, Carr A. Prospective evaluation of the effects of antiretroviral therapy on body composition in HIV-1-infected men starting therapy. AIDS (London, England). 2003 May 2:17(7):971-9 [PubMed PMID: 12700446]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFiorenza CG,Chou SH,Mantzoros CS, Lipodystrophy: pathophysiology and advances in treatment. Nature reviews. Endocrinology. 2011 Mar [PubMed PMID: 21079616]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGlidden DV, Mulligan K, McMahan V, Anderson PL, Guanira J, Chariyalertsak S, Buchbinder SP, Bekker LG, Schechter M, Grinsztejn B, Grant RM. Metabolic Effects of Preexposure Prophylaxis With Coformulated Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate and Emtricitabine. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018 Jul 18:67(3):411-419. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy083. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29415175]

Ranade K, Geese WJ, Noor M, Flint O, Tebas P, Mulligan K, Powderly W, Grinspoon SK, Dube MP. Genetic analysis implicates resistin in HIV lipodystrophy. AIDS (London, England). 2008 Aug 20:22(13):1561-8. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830a9886. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18670214]

Zanone Poma B, Riva A, Nasi M, Cicconi P, Broggini V, Lepri AC, Mologni D, Mazzotta F, Monforte AD, Mussini C, Cossarizza A, Galli M, Icona Foundation Study Group. Genetic polymorphisms differently influencing the emergence of atrophy and fat accumulation in HIV-related lipodystrophy. AIDS (London, England). 2008 Sep 12:22(14):1769-78. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830b3a96. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18753860]

Srinivasa S, Garcia-Martin R, Torriani M, Fitch KV, Carlson AR, Kahn CR, Grinspoon SK. Altered pattern of circulating miRNAs in HIV lipodystrophy perturbs key adipose differentiation and inflammation pathways. JCI insight. 2021 Sep 22:6(18):. pii: e150399. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.150399. Epub 2021 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 34383714]

Mallon PW, Cooper DA, Carr A. HIV-associated lipodystrophy. HIV medicine. 2001 Jul:2(3):166-73 [PubMed PMID: 11737397]

Guaraldi G, Fontdevila J, Christensen LH, Orlando G, Stentarelli C, Carli F, Zona S, de Santis G, Pedone A, De Fazio D, Bonucci P, Martínez E. Surgical correction of HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. AIDS (London, England). 2011 Jan 2:25(1):1-12. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833f1463. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20975513]

Study of Fat Redistribution and Metabolic Change in HIV Infection (FRAM). Fat distribution in women with HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2006 Aug 15:42(5):562-71 [PubMed PMID: 16837863]

Wohl D, Scherzer R, Heymsfield S, Simberkoff M, Sidney S, Bacchetti P, Grunfeld C, FRAM Study Investigators. The associations of regional adipose tissue with lipid and lipoprotein levels in HIV-infected men. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2008 May 1:48(1):44-52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816d9ba1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18360291]

Moyle GJ, Sabin CA, Cartledge J, Johnson M, Wilkins E, Churchill D, Hay P, Fakoya A, Murphy M, Scullard G, Leen C, Reilly G, RAVE (Randomized Abacavir versus Viread Evaluation) Group UK. A randomized comparative trial of tenofovir DF or abacavir as replacement for a thymidine analogue in persons with lipoatrophy. AIDS (London, England). 2006 Oct 24:20(16):2043-50 [PubMed PMID: 17053350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTebas P, Zhang J, Yarasheski K, Evans S, Fischl MA, Shevitz A, Feinberg J, Collier AC, Shikuma C, Brizz B, Sattler F, AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG). Switching to a protease inhibitor-containing, nucleoside-sparing regimen (lopinavir/ritonavir plus efavirenz) increases limb fat but raises serum lipid levels: results of a prospective randomized trial (AIDS clinical trial group 5125s). Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2007 Jun 1:45(2):193-200 [PubMed PMID: 17527093]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFisac C, Fumero E, Crespo M, Roson B, Ferrer E, Virgili N, Ribera E, Gatell JM, Podzamczer D. Metabolic benefits 24 months after replacing a protease inhibitor with abacavir, efavirenz or nevirapine. AIDS (London, England). 2005 Jun 10:19(9):917-25 [PubMed PMID: 15905672]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoyle GJ, Andrade-Villanueva J, Girard PM, Antinori A, Salvato P, Bogner JR, Hay P, Santos J, Astier L, Pans M, Balogh A, Biguenet S, ReAL Study Team. A randomized comparative 96-week trial of boosted atazanavir versus continued boosted protease inhibitor in HIV-1 patients with abdominal adiposity. Antiviral therapy. 2012:17(4):689-700. doi: 10.3851/IMP2083. Epub 2012 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 22388634]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGrinspoon S. Use of thiazolidinediones in HIV-infected patients: what have we learned? The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007 Jun 15:195(12):1731-3 [PubMed PMID: 17492586]

Slama L, Lanoy E, Valantin MA, Bastard JP, Chermak A, Boutekatjirt A, William-Faltaos D, Billaud E, Molina JM, Capeau J, Costagliola D, Rozenbaum W. Effect of pioglitazone on HIV-1-related lipodystrophy: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial (ANRS 113). Antiviral therapy. 2008:13(1):67-76 [PubMed PMID: 18389900]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLoutfy MR, Raboud JM, Antoniou T, Kovacs C, Shen S, Halpenny R, Ellenor D, Ezekiel D, Zhao A, Beninger F. Immediate versus delayed polyalkylimide gel injections to correct facial lipoatrophy in HIV-positive patients. AIDS (London, England). 2007 May 31:21(9):1147-55 [PubMed PMID: 17502725]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFunk E, Bressler FJ, Brissett AE. Contemporary surgical management of HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2006 Jun:134(6):1015-22 [PubMed PMID: 16730549]

McComsey GA, Walker UA, Budhathoki CB, Su Z, Currier JS, Kosmiski L, Naini LG, Charles S, Medvik K, Aberg JA, AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5229 Team. Uridine supplementation in the treatment of HIV lipoatrophy: results of ACTG 5229. AIDS (London, England). 2010 Oct 23:24(16):2507-15. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ea9bc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20827170]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThöni GJ, Fedou C, Brun JF, Fabre J, Renard E, Reynes J, Varray A, Mercier J. Reduction of fat accumulation and lipid disorders by individualized light aerobic training in human immunodeficiency virus infected patients with lipodystrophy and/or dyslipidemia. Diabetes & metabolism. 2002 Nov:28(5):397-404 [PubMed PMID: 12461477]

Kohli R, Shevitz A, Gorbach S, Wanke C. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of metformin for the treatment of HIV lipodystrophy. HIV medicine. 2007 Oct:8(7):420-6 [PubMed PMID: 17760733]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFalutz J, Allas S, Blot K, Potvin D, Kotler D, Somero M, Berger D, Brown S, Richmond G, Fessel J, Turner R, Grinspoon S. Metabolic effects of a growth hormone-releasing factor in patients with HIV. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Dec 6:357(23):2359-70 [PubMed PMID: 18057338]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFalutz J, Potvin D, Mamputu JC, Assaad H, Zoltowska M, Michaud SE, Berger D, Somero M, Moyle G, Brown S, Martorell C, Turner R, Grinspoon S. Effects of tesamorelin, a growth hormone-releasing factor, in HIV-infected patients with abdominal fat accumulation: a randomized placebo-controlled trial with a safety extension. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2010 Mar:53(3):311-22. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181cbdaff. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20101189]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePavlidis L, Spyropoulou GA, Demiri E. Comparing Efficacy and Costs of Four Facial Fillers in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Associated Lipodystrophy: A Clinical Trial. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2018 Oct:142(4):583e-584e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004741. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30036337]

Andrade GA, Coltro PS, Barros ME, Müller Neto BF, Lima RV, Farina JA Jr. Gluteal Augmentation With Intramuscular Implants in Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus With Lipoatrophy Related to the Use of Antiretroviral Therapy. Annals of plastic surgery. 2017 Nov:79(5):426-429. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001158. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28604545]

Hausauer AK, Jones DH. Long-Term Correction of Iatrogenic Lipoatrophy With Volumizing Hyaluronic Acid Filler. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2018 Nov:44 Suppl 1():S60-S62. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001417. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30359336]

Lake JE, Stanley TL, Apovian CM, Bhasin S, Brown TT, Capeau J, Currier JS, Dube MP, Falutz J, Grinspoon SK, Guaraldi G, Martinez E, McComsey GA, Sattler FR, Erlandson KM. Practical Review of Recognition and Management of Obesity and Lipohypertrophy in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2017 May 15:64(10):1422-1429. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix178. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28329372]