Introduction

Perforating dermatoses are a heterogeneous group that is characterized by a papulonodular rash with transepidermal elimination of dermal components. Traditionally, four classical forms of primary perforating dermatosis have been described, where the transepidermal elimination mechanism represents the hallmark of the disease: Kyrle disease (KD), reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC), elastosis perforans serpiginosum (EPS), and perforating folliculitis (PF).[1]

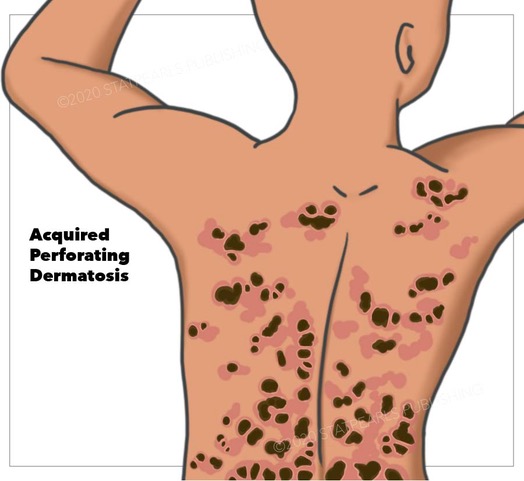

Elastosis perforans serpiginosum begins in childhood and characteristically presents with the elimination of elastic fibers. Reactive perforating collagenosis also occurs during childhood with the expulsion of collagen fibers. In perforating folliculitis, it is the content of the follicle, with or without collagen or elastic fibers, that gets eliminated. Finally, Kyrle disease presents with transepidermal elimination of abnormal keratin.[2] However, there is some controversy in the literature considering the classification of KD. While a few authors consider KD being an acquired form of perforating dermatosis, some define it as a variant of prurigo nodularis, which represents the end-stage of excoriated folliculitis.[3]The secondary form of this condition is known as acquired perforating dermatosis (APD). See Image. Acquired Perforating Dermatosis.

The term was proposed by Rapini in 1989 to designate all the perforating dermatoses affecting adults with diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic renal failure (CRF) and rarely, other systemic diseases, regardless of the eliminated dermal material.[3]

Commonly, patients with APD present with umbilicated papules and plaques with predilection sites that include the trunk and extremities.[4]

Although the pathogenesis of APD remains unclarified, some authors suggested that trauma and microvasculopathy may be the triggers of transepidermal elimination and degeneration of the collagen fibers.[5]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Exact etiology is not well understood, but there appears to be a genetic predisposition in some cases. Many cases occur in association with DM, CRF, and liver disease.

Epidemiology

Both sexes are equally affected. Acquired perforating dermatosis usually occurs during the fifth decade of life.[6]

The exact prevalence and incidence of acquired perforating dermatosis are unknown. In a retrospective study of patients diagnosed with APD between 2002 and 2014, included 33 patients. This estimated incidence was 2.53 cases per 100000 inhabitants per year. While this reported incidence is considered to be very low, the authors believed that actual APD occurs more commonly. The disease could potentially be underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed as simple excoriations.[4][7]

According to published studies, acquired reactive perforating collagenosis (ARPC) was found to be the most common form while KD and PF were the least frequent types of APD.[6]

Previous reports have documented the association of acquired perforating dermatosis with various systemic diseases, especially CRF, DM or both.[5][8][9] suspected that dialysis treatment plays a key factor in the development of APD in diabetic patients.[9]

Other associated disorders rarely reported include hepatic dysfunction, HIV infection, hypothyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, atopic dermatitis and cancers such as liver carcinoma, pancreas adenocarcinoma, Hodgkin’s disease, and myelodysplastic syndrome.[3][6][9][10]

Pathophysiology

Although the exact pathogenesis of acquired perforating dermatosis is unclear, many hypotheses exist. Patients with APD will often exhibit the Koebner phenomenon, where skin lesions develop at the sites of trauma and are exacerbated by scratching.[5][11]

Another postulated theory is that self-induced trauma to the skin damages the epidermis or dermal collagen which eventually causes the onset of APD.[3][9][11]

Moreover, leukocyte infiltration observed in skin lesions secretes interleukin-1, which is a stimulator of the synthesis of metalloproteinases, resulting in the degrading of the components of the extracellular matrix.[10]

Finally, according to some authors, the interplay of microtrauma, altered wound-healing capacities and tissue hypoxia caused by diabetes and also the microangiopathy and oxidative stress associated with CRF are considered to be the triggers of acquired perforating dermatosis.[11][12]

Histopathology

Skin biopsy is mandatory for the diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis. However, the pathological features of this condition are not uniform. They may resemble any of the four classic perforating dermatoses including RPC, EPS, PF or KD. Frequently more than one pattern is observed in the same patient.[9][11]

Therefore, many authors prefer to lump all these different diagnoses into one umbrella term of acquired perforating dermatosis. The histology of APD classically shows epidermal invagination often involving a dilated hair follicle with a keratotic plug consisting of collagen, keratin or elastic fibers. The principal diagnosis feature is the presence of a central keratotic core which is overlying a focus of epidermal perforation.[11]

History and Physical

Acquired perforating dermatosis may manifest with several polymorphous skin lesions, such as hyperkeratotic, often umbilicated, millimetric or larger papules or nodules. Erythematous or non-erythematous lesions can also be found on follicular or non-follicular regions depending on the APD type.[6]

Since pruritus is very frequent, excoriations and crusts are common presenting signs. New skin lesions can emerge due to Koebnerization.[5][6][10]

Most skin lesions develop on the extensor surfaces of the lower extremities, but APD can also be present on the trunk, scalp, or any area that the patient may scratch or rub due to pruritis.[4][11]

Faver et al. proposed diagnostic criteria of ARPC as follows: onset of the disease after the age of 18 years, the presence of umbilicated nodules or papules with a central adherent plug, and elimination of necrotic collagen tissue within an epithelium-lined crater.[8]

Evaluation

Diagnosis of acquired perforating dermatosis relies on the patient’s history, the clinical presentation of the lesions, and especially histopathology with recognition of classic histological features. Dermatoscopic findings during APD show bright white clouds and structureless grey areas which may be useful to distinguish APD from prurigo nodularis.[4] However, multiple biopsies are still the recommended procedure before establishing a definitive diagnosis.

Estimation of blood glucose level, hepatic and renal function are highly recommended to identify the underlying disease.

Treatment / Management

No controlled studies or guidelines exist for the treatment of acquired perforating dermatosis. All proposed treatments have their basis in previously published case reports or small series.

The goal of treatment should include the management of underlying disease and the relieve of the pruritus.[6][13](B2)

First-line treatment strategies include systemic or topical corticosteroids, retinoids, and keratolytic agents such as urea or salicylic acid. Emollients and oral antihistamines are frequently prescribed to relieve pruritus.[13] Nevertheless, other treatment options are often needed, and there are reports of successful outcomes with tetracyclines, retinoids, phototherapy, and allopurinol.[6][14](A1)

Tetracyclines have anti-inflammatory properties and are potent inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases.[15] Retinoids are prescribed to stabilize keratinocytes and protect collagen from both focal damage and epidermal necrolysis.[6] Allopurinol may disrupt collagen glycation via inhibition of xanthine oxidase by its antioxidant effects.[6][14](A1)

Phototherapy in the form of NB-UVB and PUVA have shown some improvement in the management of pruritus and skin lesions.[14](A1)

Finally, combination treatment, rather than monotherapy, may be more successful.

Differential Diagnosis

Prognosis

After treatment, skin lesions may disappear altogether, leaving atrophic scars or hyperpigmentation. There are only rare reports of spontaneous resolution.[6][14]

Complications

The most common complication in acquired perforating dermatosis is the secondary infection of the lesions.[10]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Due to the multifactorial nature of the disease-specific prevention strategies are difficult to identify. Patients, however, may have significant quality of life and psychological impact of the disease. Patient reassurance and education on compliance are needed to ensure adequate outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acquired perforating dermatosis often demonstrates severe pruritus and can have a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants should be aware of this characteristic dermatosis in patients with diabetes or CRF receiving hemodialysis given that early diagnosis and treatment can prevent the progression of the disease which results in an improvement of prognosis.

Also, more studies on the clinical and histological features of APD are still needed to enlighten the etiopathogenesis of this condition as the current literature remains poor and centers on case reports or small case series.

The optimal approach to addressing this rare condition involves an interprofessional team approach consisting of physicians, mid-level providers (NPs and PAs), nurses (particularly with specialty training in dermatological care) and pharmacists; this approach to caring for these patients will yield the best results. [Level V]

Media

References

Tampa M, Sârbu MI, Matei C, Mihăilă DE, Potecă TD, Georgescu SR. Kyrle's Disease in a Patient with Delusions of Parasitosis. Romanian journal of internal medicine = Revue roumaine de medecine interne. 2016 Jan-Mar:54(1):66-9 [PubMed PMID: 27141573]

Nair PA, Jivani NB, Diwan NG. Kyrle's disease in a patient of diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure on dialysis. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2015 Apr-Jun:4(2):284-6. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.154678. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25949985]

Rapini RP, Herbert AA, Drucker CR. Acquired perforating dermatosis. Evidence for combined transepidermal elimination of both collagen and elastic fibers. Archives of dermatology. 1989 Aug:125(8):1074-8 [PubMed PMID: 2757403]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGarcía-Malinis AJ,Del Valle Sánchez E,Sánchez-Salas MP,Del Prado E,Coscojuela C,Gilaberte Y, Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological study of 31 cases, emphasizing pathogenesis and treatment. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2017 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 28300323]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHong SB, Park JH, Ihm CG, Kim NI. Acquired perforating dermatosis in patients with chronic renal failure and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Korean medical science. 2004 Apr:19(2):283-8 [PubMed PMID: 15082904]

Akoglu G, Emre S, Sungu N, Kurtoglu G, Metin A. Clinicopathological features of 25 patients with acquired perforating dermatosis. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2013 Nov-Dec:23(6):864-71. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2013.2237. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24446068]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKarpouzis A, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Kouskoukis C. Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis: current status. The Journal of dermatology. 2010 Jul:37(7):585-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2010.00918.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20629824]

Faver IR,Daoud MS,Su WP, Acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Report of six cases and review of the literature. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1994 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 8157784]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSaray Y, Seçkin D, Bilezikçi B. Acquired perforating dermatosis: clinicopathological features in twenty-two cases. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2006 Jul:20(6):679-88 [PubMed PMID: 16836495]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernandes KA, Lima LA, Guedes JC, Lima RB, D'Acri AM, Martins CJ. Acquired perforating dermatosis in a patient with chronic renal failure. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2016 Sep-Oct:91(5 suppl 1):10-13. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20164619. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28300880]

Imam TH, Patail H, Khan N, Hsu PT, Cassarino DS. Acquired Perforating Dermatosis in a Patient on Peritoneal Dialysis: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case reports in nephrology. 2018:2018():5953069. doi: 10.1155/2018/5953069. Epub 2018 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 29610689]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGambichler T,Birkner L,Stücker M,Othlinghaus N,Altmeyer P,Kreuter A, Up-regulation of transforming growth factor-beta3 and extracellular matrix proteins in acquired reactive perforating collagenosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2009 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 19231643]

Haseer Koya H, Ananthan D, Varghese D, Njeru M, Curtiss C, Khanna A. Acquired reactive perforating dermatosis: a rare skin manifestation in end stage renal disease. Nephrology (Carlton, Vic.). 2014 Aug:19(8):515-6. doi: 10.1111/nep.12289. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25066144]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLukács J, Schliemann S, Elsner P. Treatment of acquired reactive perforating dermatosis - a systematic review. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2018 Jul:16(7):825-842. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13561. Epub 2018 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 29927512]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrinkmeier T, Schaller J, Herbst RA, Frosch PJ. Successful treatment of acquired reactive perforating collagenosis with doxycycline. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2002:82(5):393-5 [PubMed PMID: 12430750]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence