Introduction

The coronary venous system generally receives minimal attention in the medical literature. Even though the coronary sinus is a major access site for many invasive cardiology procedures, healthcare professionals rarely encounter diseases related to the coronary venous system. The exception is congenital malformations. Coronary sinus thrombosis is a rare and severe condition that is usually a post-procedural complication following invasive right heart instrumentation.[1] Sometimes, the condition occurs spontaneously.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Like thrombosis at any other site, coronary sinus thrombosis results from a combination of venous stasis, alteration of the coagulation profile, and vessel wall injury, such as endothelial damage. The following invasive right heart procedures have all been implicated in the etiology and pathogenesis of coronary sinus thrombosis.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

- Central venous catheter placement

- Coronary sinus instrumentation for ventricular lead placement during cardiac resynchronization

- Coronary sinus cannulation for retrograde cardioplegia during cardiopulmonary bypass for cardiac surgery (such as heart transplantation mitral valve replacement)

- Bi-ventricular defibrillator placement in severe cardiomyopathy,

- Electrophysiologic ablations for arrhythmias such as supraventricular tachycardias

- Ventriculoatrial shunt insertion for hydrocephalus

The common factor in the etiopathogenesis of all these cases has been endothelial injury leading to thrombosis.

Spontaneous non-iatrogenic coronary sinus thrombosis cases that do not involve endothelial injury but rather involve either venous stasis or alteration in coagulation profile have been documented in association with preexisting disease processes, including:

- Atrial fibrillation

- Right heart failure

- Tricuspid regurgitation

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Chronic cor pulmonale due to pulmonary fibrosis

- Kawasaki disease

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia [10][11][12][13]

It has also been documented as a complication of infective endocarditis, specifically fungal endocarditis. Sepsis and disseminated coagulopathy play an additional role in precipitating spontaneous coronary sinus thrombosis. Embolic sequela of an intra-abdominal infectious process and, recently, Crohn’s disease are also reported to be associated with spontaneous coronary sinus thrombosis.[11] Prior cases of coronary sinus thrombosis resulting from massive atrial thrombosis extending into the coronary sinus have also been reported.

Epidemiology

The occurrence of coronary sinus thrombosis is rare or at least rarely reported. However, out of the published cases, acute ones are more common (more than 80) than chronic ones. Considering the high number of patients who undergo ventricular pacing via the coronary sinus with ventricular pacemakers, the lack of reports of coronary sinus thrombosis is often surprising. Because ventricular pacemakers are usually implanted in reasonably sick patients with severe cardiomyopathy, sudden death is unlikely to be investigated with a postmortem study. In at least a few of these, the possibility that thrombosis of the coronary sinus could be associated with cardiac death remains unanswered.

No clear male or female predominance was reported. Coronary sinus thrombosis is likely under-recognized because of the rapid deterioration of these patients and the limited overall clinical experience of cardiologists with this condition. Most acute cases are usually fatal and often diagnosed on autopsy, and this curtails the reported incidence and prevalence of this condition.

Pathophysiology

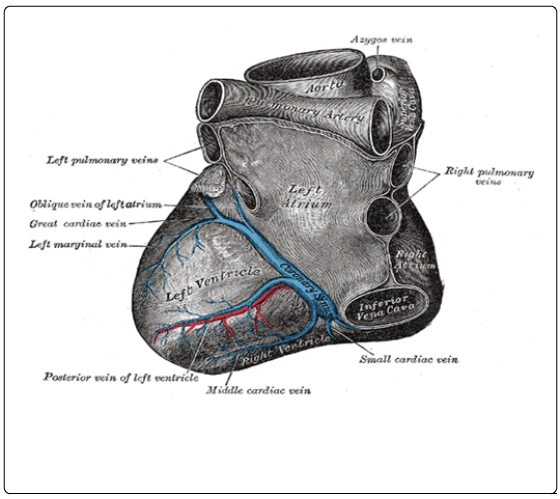

The heart's venous drainage consists of 3 separate systems (see Image. Coronary Sinus of the Heart). The first major system is the coronary sinus, which receives approximately 60% of the total cardiac venous return from the posterior myocardium via several tributaries and opens into the right atrium. The second system consists of the anterior cardiac veins, which open into the right atrium and drain most of the remaining 40%. There are many anastomotic connections between these 2 systems.

Lastly, the heart is also drained by a third minor system, the thebesian veins, consisting of many small veins, venae cordis minimae, that drain directly into all heart chambers. Sometimes, the thebesian vessels can drain up to 50% of the total cardiac venous return. Therefore, considering these anastomotic connections between the coronary sinus and the anterior cardiac veins and the drainage capability of the thebesian veins, coronary sinus thrombosis would theoretically appear to be a relatively benign entity, but it is not.

"Corona" means crown in Latin. Since this vessel forms a partial crown-like circle around the heart, it is aptly named "Coronary." The length and diameter of the coronary sinus are variable. The overall size is affected by several factors, such as the body's volume status, preload from the venous return, preexisting history of heart disease or heart surgery, and the amount of atrial myocardial tissue contributing to the vessel wall.

The coronary sinus is formed by a collection of veins joined together to form a large bore vessel, the coronary sinus, that collects blood from the heart muscle.[14] The coronary sinus has the following tributaries:

- Great cardiac vein

- Oblique vein of the left heart

- Posterior vein of the left ventricle

- Middle cardiac vein

- Small cardiac vein

The mechanism involving coronary sinus thrombosis has been suspected to be similar to thrombosis at other sites. For example, endothelial damage, hypercoagulability, and venous stasis—a triad proposed by Virchow in 1856—have been involved. Previously described cases of coronary sinus thrombosis have involved each of these factors.

The most common mechanism for triggering thrombosis is endothelial damage during invasive cardiac procedures. In spontaneous thrombosis, it is perhaps chronic stasis, as in atrial fibrillation, or a hypercoagulable state, as in malignancy.

Acute coronary sinus occlusion causes abrupt elevation of the transcapillary pressure, which, in turn, causes increased myocardial perfusion pressure even in the presence of normal, healthy coronary arteries. In addition, the venous and capillary engorgement may directly result in direct myocardial injury. Both mechanisms may lead to a transudative effusion.[15] This rapid increase in myocardial perfusion pressure decreases coronary artery blood flow, inducing ischemia, arrhythmia, progression to infarction, and sudden cardiac death.

Chronic nonocclusive coronary sinus thrombosis may not increase coronary venous pressures to the same degree but is at risk of embolization, extension into the right atrium, and fragmentation, which may also embolize to the pulmonary artery, or the systemic circulation in the presence of an atrial septal defect. Chronic progressive occlusion has also been described to be well tolerated, probably due to efficient collateral circulation between the coronary sinus, anterior cardiac, and Thebesian venous systems. On rare occasions, it could be asymptomatic without any signs of overt ischemia.

History and Physical

A high index of clinical suspicion is required to consider coronary sinus thrombosis in the diagnosis as the symptoms are not well characterized due to the shortage of published cases and relatively high mortality rate. Early studies have shown that occlusion of the coronary sinus resulted in chest pain, shortness of breath, hypotension, ischemic electrocardiogram changes such as ST-segment elevations, pericardial effusion, cardiogenic shock, or even sudden cardiac death. Mortality is high due to the nonspecific clinical presentation, rapidity of clinical deterioration, and rarity of the condition.[16][6]

Occasionally, a few cases have an insidious onset and form a partial or incomplete thrombus. Such partial or incomplete occlusion of the coronary sinus by chronic thromboses may not cause immediate death due to the formation of adequate collateral circulation among the coronary sinus, anterior cardiac vein, and Thebesain veins. Therefore, chronic occlusion of the coronary sinus with thrombus remains silent without any signs of myocardial decompensation until further complications, such as progression to complete occlusion or rupture and embolization of the thrombus develop, causing potential pulmonary embolism or myocardial dysfunction or infarction.

Evaluation

If dilated, the coronary sinus is seen on transthoracic echocardiography in the parasternal long-axis view and apical 4-chamber view. It is even more reliably visualized on transesophageal echocardiography in a modified mid-esophageal 4-chamber and bi-canal views.[14][17][14][18]

On the other hand, asymptomatic chronic coronary sinus thrombosis in patients is detected incidentally on a CT scan angiography or routine echocardiography done for other purposes. In acute severe cases where sudden cardiac death results, it is found on autopsy if one is done promptly. In the majority of deaths due to acute coronary sinus thrombosis, the antemortem diagnosis was not made due to lack of clinical suspicion until autopsy findings of thrombosed coronary sinus were discovered.

Treatment / Management

Unfortunately, the management of coronary sinus thrombosis is also poorly described. The role of aspirin is doubtful. Coronary sinus thrombectomy in acutely ill patients, followed by anticoagulation with heparin bridge to warfarin therapy, has been utilized in both stable and unstable patients. Anticoagulation alone with low-molecular-weight heparin as a bridge to warfarin or novel oral anticoagulant therapy has also been employed in clinically stable patients.[13]

Although healthcare professionals use the above treatment modalities with reasonable benefit, there is insufficient literature to elucidate any mortality or morbidity benefit from such treatments. Clear, concise guidelines to facilitate management in the long run and the role of anticoagulation therapy, especially novel oral anticoagulants, require further clinical studies.

Differential Diagnosis

Due to the nonspecificity of the clinical presentation and limited experience with coronary sinus thrombosis, it is usually not very high on the list of differential diagnoses. The following possible differential diagnoses need to be considered.

- Myocardial Infarction (MI): With a presentation of chest pain, dyspnea, hypotension, tachycardia, elevated troponins, and ischemic changes on the ECG, MI due to coronary artery disease is high on the differential. Coronary sinus thrombosis can also present with a similar picture. However, a coronary angiogram can differentiate both conditions and diagnose coronary sinus thrombosis. Establishing a clear cause and diagnosis is critical as the management of MI due to CAD is very different from MI due to Coronary sinus thrombosis.

- Pericardial effusion and tamponade: It is very pertinent to differentiate pericardial effusion due to coronary sinus thrombosis from pericardial effusion due to multiple other causes such as cancer, infection or autoimmune disorders, as again, the management differs significantly according to the etiology.

- Septic shock: Acutely decompensated cases with coronary sinus thrombosis can present with a cardiogenic shock, which has to be differentiated from septic shock. Clinical parameters like the source of infection, signs of sepsis, labs, and investigations about sepsis workup should help distinguish both conditions.

- An incidental dilated coronary sinus due to thrombosis has to be differentiated from other causes of coronary sinus dilation, such as congenital disorders causing an abnormally increased venous return to the coronary sinus. These include patent left SVC, anomalous hepatic and pulmonary venous drainage, and coronary arteriovenous fistulae. A dilated coronary sinus can also be seen in right heart failure with ventricular dysfunction and conditions causing increased right atrial pressure, such as pulmonary hypertension.

Prognosis

The prognosis is poor, especially in acute presentations, with more than 80% of patients developing devastating complications as mentioned earlier resulting in cardiac death. However, asymptomatic patients with an incidental diagnosis of chronic coronary sinus thrombosis are less reported than acute ones, and the prognosis is better on aggressive treatment with effective anticoagulation with or without thrombectomy.

Complications

As mentioned earlier, coronary sinus thrombosis can have devastating fatal complications such as acute myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, cardiogenic shock, and even sudden cardiac death if early diagnosis and treatment is not initiated.[7][9]

Consultations

Due to the complex nature of the presentation of coronary sinus thrombosis, especially in acute presentations, critical care consultation is warranted. Also, cardiology and electrophysiology consultations would prove to be prudent if time and the patient's clinical presentations permit.

Pearls and Other Issues

Coronary sinus thrombosis is a rare but potentially deadly complication of many invasive cardiac procedures, many of which are performed on a daily basis, such as central venous catheter placements or ventricular pacing. It may present with ST elevations on ECG, pericardial tamponade, and cardiogenic shock. Early recognition and immediate treatment of the thrombosed coronary sinus is critical if resuscitation is to be successful.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Coronary sinus thrombosis is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes pharmacists. Despite the known complications, there are no clear guidelines or recommendations to assist physicians in the long-term management of such patients. The role of anticoagulation remains unclear and warrants further investigation. A systematic study of the incidence and sequelae of coronary sinus thrombosis in patients who undergo manipulation of the coronary sinus is certainly warranted. Case reports indicate poor outcomes in symptomatic patients.[19]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bapat VN, Hardikar AA, Porwal MM, Agrawal NB, Tendolkar AG. Coronary sinus thrombosis after cannulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1996 Nov:62(5):1506-7 [PubMed PMID: 8893593]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEconomopoulos GC, Michalis A, Palatianos GM, Sarris GE. Management of catheter-related injuries to the coronary sinus. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2003 Jul:76(1):112-6 [PubMed PMID: 12842523]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFiguerola M, Tomás MT, Armengol J, Bejar A, Adrados M, Bonet A. Pericardial tamponade and coronary sinus thrombosis associated with central venus catheterization. Chest. 1992 Apr:101(4):1154-5 [PubMed PMID: 1555439]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCoronary sinus thrombus without spontaneous contrast., Floria M,Negru D,Antohe I,, Journal of thrombosis and thrombolysis, 2016 Oct [PubMed PMID: 27116357]

Hazan MB, Byrnes DA, Elmquist TH, Mazzara JT. Angiographic demonstration of coronary sinus thrombosis: a potential consequence of trauma to the coronary sinus. Catheterization and cardiovascular diagnosis. 1982:8(4):405-8 [PubMed PMID: 7127465]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParmar RC, Kulkarni S, Nayar S, Shivaraman A. Coronary sinus thrombosis. Journal of postgraduate medicine. 2002 Oct-Dec:48(4):312-3 [PubMed PMID: 12571393]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRamsaran EK, Sadigh M, Miller D. Sudden cardiac death due to primary coronary sinus thrombosis. Southern medical journal. 1996 May:89(5):531-3 [PubMed PMID: 8638186]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUnexpected sudden death from coronary sinus thrombosis. An unusual complication of central venous catheterization., Suárez-Peñaranda JM,Rico-Boquete R,Muñoz JI,Rodríguez-Núñez A,Martínez Soto MI,Rodríguez-Calvo M,Concheiro-Carro L,, Journal of forensic sciences, 2000 Jul [PubMed PMID: 10914599]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYeo KK, Davenport J, Raff G, Laird JR. Life-threatening coronary sinus thrombosis following catheter ablation: case report and review of literature. Cardiovascular revascularization medicine : including molecular interventions. 2010 Oct-Dec:11(4):262.e1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2010.01.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20934660]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKitazawa S, Kitazawa R, Kondo T, Mori K, Matsui T, Watanabe H, Watanabe M. Fatal cardiac tamponade due to coronary sinus thrombosis in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a case report. Cases journal. 2009 Nov 27:2():9095. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9095. Epub 2009 Nov 27 [PubMed PMID: 20062732]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMartin J, Nair V, Edgecombe A. Fatal coronary sinus thrombosis due to hypercoagulability in Crohn's disease. Cardiovascular pathology : the official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Pathology. 2017 Jan-Feb:26():1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2016.09.008. Epub 2016 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 27776257]

Milligan G, Moscona JC. Coronary sinus thrombosis: Echocardiographic visualization in a patient with known risk factors. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2018 Oct:46(8):555-557. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22578. Epub 2018 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 29430659]

Neri E, Tripodi A, Tucci E, Capannini G, Sassi C. Dramatic improvement of LV function after coronary sinus thromboembolectomy. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000 Sep:70(3):961-3 [PubMed PMID: 11016343]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHart MA, Simegn MA. Pylephlebitis presenting as spontaneous coronary sinus thrombosis: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2017 Nov 2:11(1):309. doi: 10.1186/s13256-017-1479-9. Epub 2017 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 29092714]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStewart RH, Rohn DA, Allen SJ, Laine GA. Basic determinants of epicardial transudation. The American journal of physiology. 1997 Sep:273(3 Pt 2):H1408-14 [PubMed PMID: 9321832]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKachalia A, Sideras P, Javaid M, Muralidharan S, Stevens-Cohen P. Extreme clinical presentations of venous stasis: coronary sinus thrombosis. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2013 Nov:61(11):841-3 [PubMed PMID: 24974504]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrogel JK, Weiss SJ, Kohl BA. Transesophageal echocardiography diagnosis of coronary sinus thrombosis. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2009 Feb:108(2):441-2. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818f61e3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19151269]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNathani S, Parakh N, Chaturvedi V, Tyagi S. Giant coronary sinus. Texas Heart Institute journal. 2011:38(3):310-1 [PubMed PMID: 21720482]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceValente AM, Lock JE, Gauvreau K, Rodriguez-Huertas E, Joyce C, Armsby L, Bacha EA, Landzberg MJ. Predictors of long-term adverse outcomes in patients with congenital coronary artery fistulae. Circulation. Cardiovascular interventions. 2010 Apr:3(2):134-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.109.883884. Epub 2010 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 20332380]