Introduction

Healthcare providers have used many regional, anesthetic modalities to provide analgesia for the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis. While each of these modalities has a wide range of applications, their utility is limited by a few contraindications.[1][2][3][4] As an alternative to neuraxial anesthetics, truncal nerve blocks and interfascial plane blocks for postoperative analgesia have been used for nearly a half-century. Practitioners initially used these as ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric, rectus sheath blocks, and in the early 21st century, transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks.[5] This article reviews a recent variation of the TAP block developed by Rafael Blanco, known as the quadratus lumborum block (QLB).

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The QLB differs from the TAP. It is a block of the posterior abdominal wall. It is also referred to as an interfascial plane block because it requires the injection of a local anesthetic into the thoracolumbar fascia (TLF), which is a posterior extension of the abdominal wall muscle fascia and encompasses the back muscles (quadratus lumborum [QL], psoas major [PM], and the erector spinae [ES] muscles). The TLF extends posteriorly to connect with the lumbar paravertebral region. It has 3 layers – anterior, middle, and posterior – based on its relation to the back muscles it encapsulates. The TLF extends from the lumbar spine to the thoracic spine in a craniocaudal direction.[6]

The TLF contains mechanoreceptors, nociceptors, and sympathetic fibers. The spread of local anesthetic to the paravertebral space and inhibition of these sympathetic fibers is believed to be responsible for the visceral pain coverage provided by this block.[7]

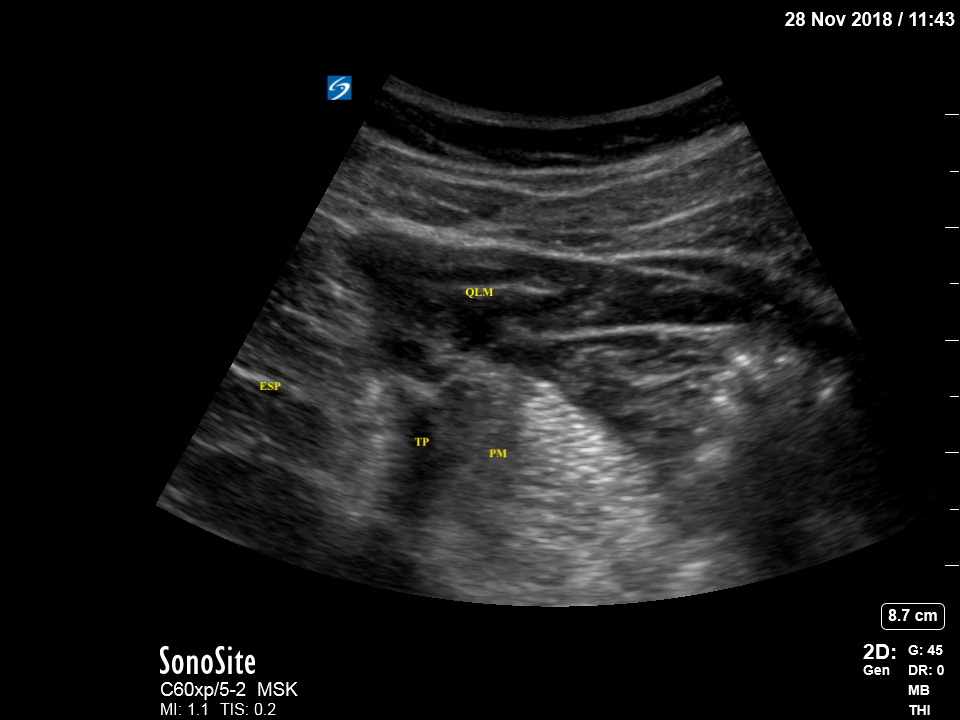

Variants of this block have been described, each involving a different injection site relative to the quadratus lumborum muscle. QL1 or lateral QLB refers to the deposition of local anesthetic lateral to the QL muscle. QL2 or posterior QLB refers to injection posterior to the QL muscle (anterior to the TLF separating QL muscle from erector spinae and latissimus dorsi muscles) in an area termed the "lumbar interfascial triangle." QL3 or anterior QLB, also referred to as the transmuscular approach due to the typical needle approach, refers to injection anterior to the QL muscle at the level of the L4 vertebral body. To acquire the ultrasound view for this block, the clinician should obtain the "shamrock sign," which consists of the transverse process of L4 as the "stem" and psoas major, QL, and erector spinae as "3 cloves of the shamrock."[8] QL4 or intramuscular QL block involves the injection into the muscle itself.

Indications

The QLB produces a broad distribution of local anesthetic resulting in a large area of sensory inhibition of (T7 through L1 in most cases). Therefore, QLBs may be used to provide postoperative analgesia for abdominal and pelvic regions. For this reason, the QLB is often used in the treatment of pain after abdominal, obstetric, gynecologic, and urologic surgeries. There are also case reports of QLBs being used successfully in the hip, femur, and lumbar vertebrae surgeries.[9][10]

Contraindications

The QLB has similar contraindications to other fascia plane blocks, such as the transversus abdominis plane block or the fascia iliaca block. These absolute contraindications include the following[1][2]:

- Patient refusal

- True local anesthetic allergy

- Risk of local anesthetic toxicity; in other words, the patient has already received the maximum recommended local anesthesia dose.

- Local infection at the procedure site

There is controversy about whether the QLB or other plane blocks can be safely performed during a coagulopathy or in a patient receiving anticoagulants.[2] Some practitioners suggest that plane blocks may be safe with altered coagulation.[3] The most recently published American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine evidence-based guidelines for regional anesthesia use in patients receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy caution against deep regional anesthetic procedures in anticoagulated patients because multiple case reports found that such situations resulted in significant morbidity.[4]

Equipment

Equipment includes:

- Skin antiseptic

- Sterile towels

- Sterile gauze

- 100 to 150 cm 22-gauge needle for a local anesthetic injection

- Local anesthetic

- Sterile gloves

- Ultrasound machine

- Lateral, posterior, and intramuscular approaches: High frequency (6 to 15 MHz) linear ultrasound probe transducer

- Anterior (QL3) approach: Lower frequency (2 to 6 MHz) curvilinear ultrasound transducer

- ECG monitor

- Blood pressure monitor

- Pulse oximetry

Generally, a long-acting local anesthetic such as 0.2% ropivacaine or 0.25% bupivacaine is chosen to maximize pain control. Maximum allowable dosage should be calculated, especially if the performance of bilateral blocks is anticipated.

Personnel

A provider trained in ultrasound-guided, regional anesthesia is the only required personnel. However, an assistant such as a nurse or an additional provider can assist in monitoring patients and administer medications as needed.

Preparation

The provider must discuss the risks, benefits, and alternatives with the patient and then obtain informed consent. The practitioner should position the patient for the block: supine position for lateral or posterior QLB, lateral decubitus for intramuscular QLB, or anterior QLB. The practitioner should identify the correct location and anatomy under ultrasound and then clean the patient's skin with chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine.

Technique or Treatment

For the lateral QLB, the patient is positioned supine or lateral position)with an ultrasound probe applied to the flank between the costal margin and the iliac crest in the anterior axillary line (triangle of Petit). The 3 abdominal muscle layers (external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis) are identified and traced posteriorly to identify the TLF and the back muscles – QL, PM, ES, and latissimus dorsi). The provider inserts the needle in an in-plane approach and advances it through the anterior abdominal muscles until it reaches the anterolateral edge of QL. Proper placement results in the spread of local anesthetic between QL and the middle layer of the TLF.

For the anterior QLB, the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position with the ultrasound probe placed above the iliac crest at the mid-axillary line. The provider moves the probe posteriorly to identify the "shamrock sign." They then insert the needle in an in-plane approach through the QL muscle and the middle TLF layer between QL and PM. Correct needle placement and injection results in the spread of local anesthetic between these 2 muscles.

For the posterior QLB, the patient is positioned supine as with the lateral QLB. The provider identifies the posterior border of QL and places the needle tip at that point. Proper placement should result in the spread of local anesthetic through the middle TLF layer and into the interfascial triangle.

For the Intramuscular QLB, the patient should be placed in the supine or lateral decubitus position. Following identification of QL, the practitioner inserts the needle in an in-plane approach and an anterolateral to posteromedial direction with an injection of a local anesthetic directly into the muscle.

Complications

Practitioners must take care to perform this block under a sterile technique to avoid infection. QLBs have a lower theoretical risk of infection than more central neuraxial approaches, and there are no reported cases of infectious complications from QLB. History of coagulopathy or anticoagulation use should be addressed before performing the block to avoid excessive bleeding or hematoma formation.[11]

Any regional anesthesia procedure utilizing local anesthetic medications is associated with potential local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) due to systemic absorption of local anesthetics. The QLB is associated with lower plasma ropivacaine levels than TAP blocks, potentially making the QLB safer in that regard.[12] There are no reported cases of LAST from QLB.

Clinical Significance

QLB has several advantages over previously described truncal nerve blocks, including greater analgesic and opioid-sparing effects. Evidence suggests possible improved visceral pain coverage with the anterior, and possibly posterior, QLB.[6] Additionally, the location of the injection sites provides an additional element of safety since the targets for injection are relatively distant from the peritoneal cavity, abdominal organs, and large blood vessels.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Ensuring patient safety in a team setting requires a closed-loop communication system. Before these blocks, a timeout identifying correct patient information, allergies, and the procedure being performed is vital. Consent should be verified with the patient if possible and all other providers involved with their care. The use of procedural checklists has proven to reduce miscommunication and wrong site or side regional anesthesia procedures.[13][14]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Hutschenreuter K. [Indications and contraindications of regional anesthesia (author's transl)]. Langenbecks Archiv fur Chirurgie. 1977 Nov:345():487-92 [PubMed PMID: 593004]

Young MJ, Gorlin AW, Modest VE, Quraishi SA. Clinical implications of the transversus abdominis plane block in adults. Anesthesiology research and practice. 2012:2012():731645. doi: 10.1155/2012/731645. Epub 2012 Jan 19 [PubMed PMID: 22312327]

Mrunalini P, Raju NV, Nath VN, Saheb SM. Efficacy of transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing emergency laparotomies. Anesthesia, essays and researches. 2014 Sep-Dec:8(3):377-82. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.143153. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25886339]

Horlocker TT, Vandermeuelen E, Kopp SL, Gogarten W, Leffert LR, Benzon HT. Regional Anesthesia in the Patient Receiving Antithrombotic or Thrombolytic Therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (Fourth Edition). Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2018 Apr:43(3):263-309. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000763. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29561531]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSmith BE, Suchak M, Siggins D, Challands J. Rectus sheath block for diagnostic laparoscopy. Anaesthesia. 1988 Nov:43(11):947-8 [PubMed PMID: 2975148]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUeshima H, Otake H, Lin JA. Ultrasound-Guided Quadratus Lumborum Block: An Updated Review of Anatomy and Techniques. BioMed research international. 2017:2017():2752876. doi: 10.1155/2017/2752876. Epub 2017 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 28154824]

Tesarz J, Hoheisel U, Wiedenhöfer B, Mense S. Sensory innervation of the thoracolumbar fascia in rats and humans. Neuroscience. 2011 Oct 27:194():302-8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.07.066. Epub 2011 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 21839150]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEl-Boghdadly K, Elsharkawy H, Short A, Chin KJ. Quadratus Lumborum Block Nomenclature and Anatomical Considerations. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 Jul-Aug:41(4):548-9. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000411. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27315184]

Ueshima H, Yoshiyama S, Otake H. RETRACTED: The ultrasound-guided continuous transmuscular quadratus lumborum block is an effective analgesia for total hip arthroplasty. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2016 Jun:31():35. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.12.033. Epub 2016 Mar 22 [PubMed PMID: 27185672]

Ueshima H, Hiroshi O. RETRACTED: Lumbar vertebra surgery performed with a bilateral posterior quadratus lumborum block. Journal of clinical anesthesia. 2017 Sep:41():61. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.06.012. Epub 2017 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 28802611]

Akerman M, Pejčić N, Veličković I. A Review of the Quadratus Lumborum Block and ERAS. Frontiers in medicine. 2018:5():44. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00044. Epub 2018 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 29536008]

Murouchi T, Iwasaki S, Yamakage M. Quadratus Lumborum Block: Analgesic Effects and Chronological Ropivacaine Concentrations After Laparoscopic Surgery. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 Mar-Apr:41(2):146-50. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000349. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26735154]

Slocombe P, Pattullo S. A site check prior to regional anaesthesia to prevent wrong-sided blocks. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2016 Jul:44(4):513-6 [PubMed PMID: 27456184]

Mancone AG, Dickey AR, Fitzgerald BM, Kraus GP, Dhanjal ST. LAST Double Check - A Comprehensive Pre-Regional Checklist for the Busy Institution. Military medicine. 2018 Sep 1:183(9-10):e281-e285. doi: 10.1093/milmed/usx220. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29554361]