Introduction

Axillary lymphadenectomy, or axillary dissection, is a procedure where a surgeon dissects out the lymph nodes within the axilla en bloc. This is done most commonly for cancer workups and treatment. This procedure used to be done widely, but it is done much more selectively in recent years with advances in early detection and treatment, as well as numerous studies showing no increased benefit to this procedure in certain circumstances. The most common disease process that this is done for is breast cancer. While the focus of this article will be on breast cancer, it is important to note that sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary lymphadenectomy can be performed for lung cancer and melanoma as well.[1]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Axillary anatomy is very important to know for performing axillary lymphadenectomy. There are three levels of axillary lymph nodes. Typically, level one and level two lymph nodes are taken during this dissection. Level three nodes are not sought after in current times. Level one nodes are lateral to the pectoralis minor muscle, level two lymph nodes are deep to the pectoralis minor muscle, and level three lymph nodes are medial to the pectoralis minor muscle. Rotter's nodes are lymph nodes between the pectoralis major and minor muscles. The axillary fat pad is deep to the subcutaneous fat and does have a different appearance so that it is usually distinguishable. The borders of the axilla are especially important as they act as a guide to orient the surgeon during the procedure and indicate where the dissection should be performed. The important borders of the axilla are the axillary vein superiorly, which can act as the first structure to identify during an especially difficulty dissection. The medial border is the chest wall. The pectoralis major and pectoralis minor make the anterior border. The axillary skin is the lateral border. The posterior border is the latissimus dorsi muscle. There are multiple nerves within this area that great care must be taken to avoid injuring. The most likely injured is the intercostobrachial nerve. When this is transected, it causes paresthesias to the medial upper arm. The long thoracic nerve, thoracodorsal neurovascular bundle, and lateral thoracic artery are also within the region and can be at risk for injury. The long thoracic nerve innervates the serratus anterior muscle. Injury to the long thoracic nerve results in winged scapula and patients may complain of upper extremity weakness or decreased range of motion of the shoulder. The thoracodorsal nerve innervates the latissimus dorsi muscle, and injury causes loss of function.

Indications

In most cases, axillary sentinel lymph node biopsy has taken the place of axillary dissection in clinically node-negative patients. Indications for axillary lymphadenectomy include[2]:

Clinically positive axillary lymph nodes that have been proven with biopsy in a patient that is not planning on undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Patients with inflammatory breast cancer

Patients who do not meet guidelines for the Z0011 criteria

Patients with three or more axillary sentinel nodes that are positive for cancer

Persistently positive lymph nodes after neoadjuvant therapy

Axillas with failed radiotracer and/or lymphazurin/methylene blue during sentinel lymph node biopsy

Axillary lymph node recurrence after prior breast cancer treatment[3][4][5][6][7][8]

Contraindications

There are typically not any absolute contraindications to axillary lymphadenectomy. If a patient has recurrent breast disease or a second primary with a history of an axillary dissection on the same side, an axillary dissection is not usually performed for new cancer. In current times, most patients will be able to have a sentinel lymph node biopsy in place of a formal axillary dissection, except, of course, for the indications listed above. If a patient has distant metastasis, an axillary dissection is not usually necessary with evidence of grossly metastatic disease.

Equipment

An operating suite is needed for this procedure, along with the necessary equipment for anesthesia, as well as standard surgical instrument sets. Typically a radiotracer probe is not needed for this procedure. It may be in the room if the initial procedure was a sentinel lymph node biopsy and was converted to an axillary lymphadenectomy, but is not used for this procedure.

Personnel

General surgeons, surgical oncologists, or breast surgeons typically perform this procedure. This procedure is done in the operating room, typically with general anesthesia. The usual operating room personnel are required, including anesthesiology, surgical technologist, and circulating nurses. Pathologists will then review the specimen after the procedure is completed. Once pathology is back, surgeons, in combination with radiation and medical oncologists, will decide on the necessary next steps in treatment.

Preparation

These patients are typically brought to breast tumor board prior to surgery so that a prospective plan is made before taking the patients for surgery. The surgeon then obtains informed consent before the operation. This includes the patients with possible axillary dissection during a sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure, in addition to patients who had a planned axillary lymphadenectomy. Radiotracer and/or lymphazurin/methylene blue are not necessary for this procedure but may have been used if the initial procedure was a sentinel lymph node biopsy that was converted to axillary dissection.[9]

Technique or Treatment

The patient's axilla is prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. The patient is supine with the arm of the affected side at 90 to 100 degrees of abduction on an arm board. The landmark used superficially for the axillary incision is the inferior axillary hair line. An oblique incision is made, and electrocautery is typically used to dissect through the subcutaneous tissue to access the axillary fat pad once the clavipectoral fascia is incised. Once this is identified, many surgeons will identify the axillary vein and begin dissection inferior to this. Retraction is used to elevate the pectoralis muscles to dissect out the level two lymph nodes. Typically, most of this dissection can be performed bluntly. The axillary specimen is usually removed en bloc. The cavity is examined, and hemostasis is achieved as necessary, taking care to not injure any of the surrounding nerves or major vessels. A small drain may be left in place, with the exit point at a site other than the incision. The drain is sutured in place. The axillary incision is closed based on surgeon preference. Some sort of compressive dressing can be used postoperatively to provide some support and decrease seroma formation in addition to the drain.[10]

Complications

Axillary lymphadenectomy does carry increased morbidity when compared to sentinel lymph node biopsy, which is, in part, why it is performed more selectively in recent years. Typical complications with any surgery include infection and bleeding. Complications specific to this procedure include temporarily decreased range of motion of the shoulder, hematoma, lymphedema, lymphocele, lymphatic fibrosis, lymphangiosarcoma, injury to vasculature, or nerves within the region, or axillary vein thrombosis. Drains are placed commonly after this procedure, and while not a complication in itself, prolonged need for the drain can be a complication. Typically after an axillary lymphadenectomy is performed, there is not a need for additional surgery in the same region, unless there is an axillary recurrence in the future.[11]

Clinical Significance

Axillary lymphadenectomy is done when there is already positive disease within the axilla. Typically this is done to ascertain the extent of the disease within the axilla, which is extremely important for staging. In turn, the status of the axillary nodes and stage of the patient plays a major part in the subsequent treatment that the patient will be receiving. This can include chemotherapy and radiation therapy. A ten lymph node minimum is considered an adequate axillary dissection, although if less are obtained, surgeons rarely go back to surgery for additional lymph nodes. Of note, once a patient has had an axillary dissection, care is taken to avoid IV or blood pressure recordings in that arm as there is an increased risk of lymphedema compared to sentinel lymph node biopsy. Postoperatively, patients are given arm exercises and can be referred to a lymphedema clinic if this does arise.[12][5]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Breast cancer care requires an interprofessional team approach, including surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, nurse navigators, physical therapists, and more. These teams are crucial in formulating plans during breast tumor boards and in the aftercare of these patients for survivorship planning. Being up to date in all aspects of these specialties provides for the best patient care, improved patient outcomes, and overall enhances the team's performance when taking care of these patients.

Media

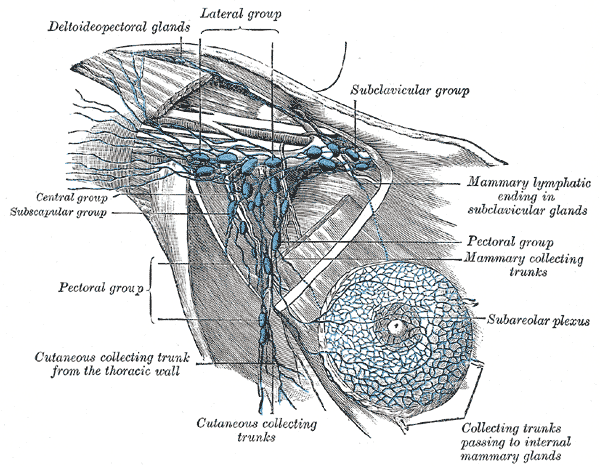

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Axillary Lymph Nodes, Illustrated anatomy includes the deltopectoral glands, lateral group, subclavicular group, central group, subscapular group, pectoral group, cutaneous collecting trunks, subareolar plexus, mammary collecting trunks, and mammary lymphatic ending in the subclavicular glands.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Black DM, Mittendorf EA. Landmark trials affecting the surgical management of invasive breast cancer. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2013 Apr:93(2):501-18. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2012.12.007. Epub 2013 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 23464699]

Ling DC, Iarrobino NA, Champ CE, Soran A, Beriwal S. Regional Recurrence Rates With or Without Complete Axillary Dissection for Breast Cancer Patients with Node-Positive Disease on Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. Advances in radiation oncology. 2020 Mar-Apr:5(2):163-170. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2019.09.006. Epub 2019 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 32280815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu D, Liu SY, Amina M, Fan ZM. [Normalization in axillary lymph node management after neoadjuvant therapy for breast cancer]. Zhonghua wai ke za zhi [Chinese journal of surgery]. 2019 Feb 1:57(2):97-101. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0529-5815.2019.02.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30704211]

de Barros ACSD, de Andrade DA. Extended Sentinel Node Biopsy in Breast Cancer Patients who Achieve Complete Nodal Response with Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy. European journal of breast health. 2020 Apr:16(2):99-105. doi: 10.5152/ejbh.2020.4730. Epub 2020 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 32285030]

Costaz H, Rouffiac M, Boulle D, Arnould L, Beltjens F, Desmoulins I, Peignaux K, Ladoire S, Vincent L, Jankowski C, Coutant C. [Strategies in case of metastatic sentinel lymph node in breast cancer]. Bulletin du cancer. 2020 Jun:107(6):672-685. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2019.09.005. Epub 2019 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 31699399]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJung J, Kim BH, Kim J, Oh S, Kim SJ, Lim CS, Choi IS, Hwang KT. Validating the ACOSOG Z0011 Trial Result: A Population-Based Study Using the SEER Database. Cancers. 2020 Apr 11:12(4):. doi: 10.3390/cancers12040950. Epub 2020 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 32290437]

Cipolla C, Valerio MR, Grassi N, Calamia S, Latteri S, Latteri M, Graceffa G, Vieni S. Axillary Nodal Burden in Breast Cancer Patients With Pre-operative Fine Needle Aspiration-proven Positive Lymph Nodes Compared to Those With Positive Sentinel Nodes. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2020 Mar-Apr:34(2):729-734. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11831. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32111777]

Dixon JM, Cartlidge CWJ. Twenty-five years of change in the management of the axilla in breast cancer. The breast journal. 2020 Jan:26(1):22-26. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13720. Epub 2019 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 31854498]

Alvarado MD, Mittendorf EA, Teshome M, Thompson AM, Bold RJ, Gittleman MA, Beitsch PD, Blair SL, Kivilaid K, Harmer QJ, Hunt KK. SentimagIC: A Non-inferiority Trial Comparing Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Versus Technetium-99m and Blue Dye in the Detection of Axillary Sentinel Nodes in Patients with Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Annals of surgical oncology. 2019 Oct:26(11):3510-3516. doi: 10.1245/s10434-019-07577-4. Epub 2019 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 31297674]

Ung O, Tan M, Chua B, Barraclough B. Complete axillary dissection: a technique that still has relevance in contemporary management of breast cancer. ANZ journal of surgery. 2006 Jun:76(6):518-21 [PubMed PMID: 16768781]

Gupta S, Gupta N, Kadayaprath G, Neha S. Use of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy and Early Physiotherapy to Reduce Incidence of Lymphedema After Breast Cancer Surgery: an Institutional Experience. Indian journal of surgical oncology. 2020 Mar:11(1):15-18. doi: 10.1007/s13193-019-01030-4. Epub 2020 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 32205962]

Krag DN, Anderson SJ, Julian TB, Brown AM, Harlow SP, Costantino JP, Ashikaga T, Weaver DL, Mamounas EP, Jalovec LM, Frazier TG, Noyes RD, Robidoux A, Scarth HM, Wolmark N. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2010 Oct:11(10):927-33. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70207-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20863759]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence