Facial Nerve Anatomy and Clinical Applications

Facial Nerve Anatomy and Clinical Applications

Introduction

The facial nerve is the seventh cranial nerve. It contains the motor, sensory, and parasympathetic (secretomotor) nerve fibers, which provide innervation to many areas of the head and neck region. The facial nerve is comprised of three nuclei:

- The main motor nucleus

- The parasympathetic nuclei

- The sensory nucleus

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

There are four major functions of the facial nerve:

- General somatic efferent (motor supply to facial muscles)

- General visceral efferent (parasympathetic secretomotor supply to submandibular and sublingual salivary glands and the lacrimal gland)

- Special visceral afferent (taste sensation from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue)

- General somatic afferent (cutaneous sensations from the pinna and the external auditory meatus).[1][2]

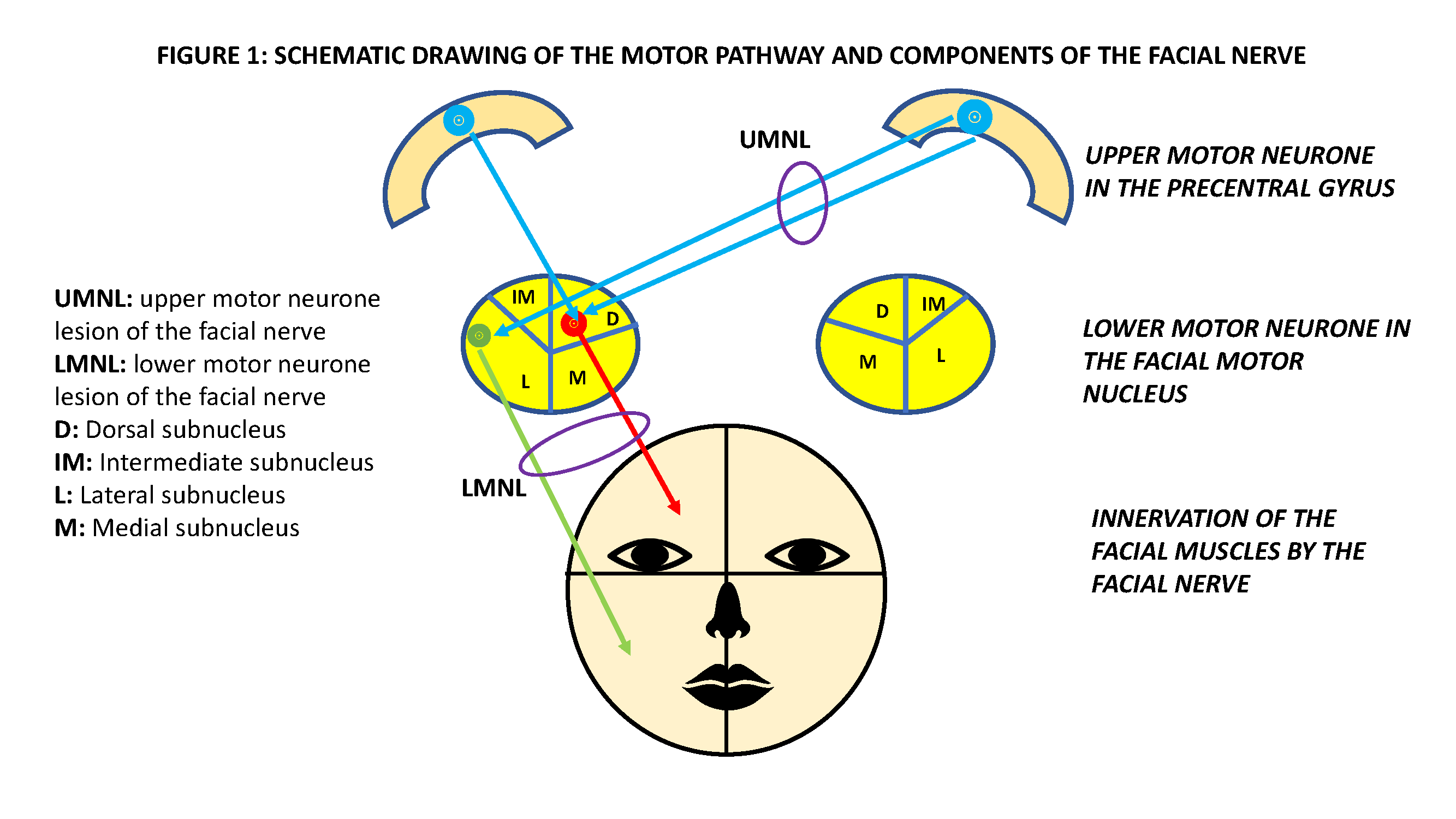

Motor Pathway

The upper motor neuron is located in the facial motor area of the precentral gyrus. The axons from the upper motor neuron travel along the ipsilateral corticobulbar tract to the lower pons, where most fibers cross to the other side and synapse with the lower motor neuron. The main motor nucleus (lower motor neuron) divides into four subnuclei; dorsal, intermediate, lateral, and medial. The dorsal subnucleus innervates the facial muscles of the ipsilateral upper quadrant and receives corticobulbar input from both hemispheres. Conversely, the lateral subnucleus is connected to contralateral corticobulbar fibers only, and it innervates muscles of the ipsilateral lower quadrant of the face (Figure 1).[3][4] Due to this difference in innervation, in an upper motor neuron facial palsy, only the contralateral lower quadrant of the face is paralyzed, while the ipsilateral half of the face suffers paralysis in a lower motor neuron facial palsy. The main motor nucleus is responsible for the voluntary control of facial muscles. Also, the motor nucleus supplies the auricular muscles, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the stapedius muscle, and the stylohyoid muscle. The emotional facial expression follows a different pathway and is under the influence of the limbic and extrapyramidal systems.[5]

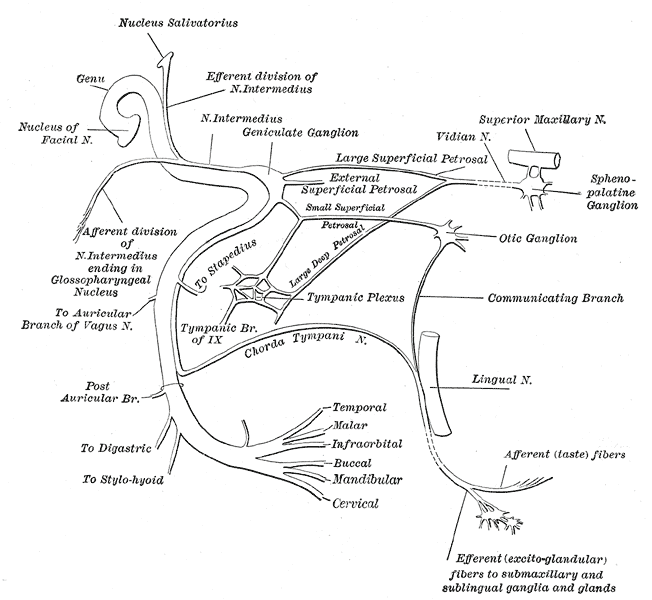

Parasympathetic Pathway

The superior salivatory and lacrimal nuclei make up the parasympathetic nuclei of the facial nerve. They are in the lower pons, posterolateral to the facial motor nucleus. Efferent fibers from the hypothalamus supply the superior salivatory nucleus. In addition, the nucleus of the solitary tract delivers information regarding taste to the superior salivatory nucleus. The superior salivatory nucleus supplies the sublingual and submandibular salivary glands, as well as the palatine and nasal glands. The inputs to the lacrimal nucleus are from (a) the hypothalamus (emotional response) and (b) the sensory trigeminal nerve (reflex lacrimation secondary to eye irritation). The parasympathetic efferent pathway to the facial nerve from the brainstem is through the nervus intermedius.[1]

Sensory Pathway

The sensory nucleus, located posterolateral to the motor nucleus and parasympathetic nuclei in the pons, receives taste information from the palate, floor of the mouth, and anterior two-thirds of the tongue. The first-order neurons of the taste fibers are in the geniculate ganglion, and the taste fibers synapse in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius (second-order neuron) in the brainstem. Axons of the second-order neurons cross to the contralateral side and ascend through the medial lemniscus to the thalamus, where they synapse with the third-order neuron. Efferents from the third-order neurons ascend through the internal capsule and the corona radiata, terminating in the taste area of the sensory cortex in the postcentral gyrus and the insula. Some projections reach the hypothalamus.[6]

General sensory fibers also have their first-order neurons located in the geniculate ganglion and the second-order neuron located in the spinal trigeminal nucleus. The sensory and parasympathetic fibers of the facial nerve are collectively bound in a fascial sheath; these structures together have the name 'nervus intermedius.'[2]

Embryology

During the third week of the embryo, the facioacoustic primordium develops, and this structure is what ultimately gives rise to the facial nerve. During the fourth week of life, the facial nerve splits into two: the chorda tympani and the caudal main trunk. At the beginning of the fifth week, the geniculate ganglion and the nervus intermedius develop. The facial muscles originate from the second branchial arch during the seventh and eighth weeks. The peripheral segment of the facial nerve undergoes extensive branching from week 10 to 15. Ossification of the bony canal takes place from the 16th week to birth.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The upper motor neuron of the facial nerve located in the precentral gyrus receives its blood supply from the middle cerebral artery, whereas the facial nucleus containing the lower motor neuron in the pons is supplied by the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, which is a branch of the basilar artery. After exiting the brainstem, up to the internal auditory meatus, the facial nerve receives its blood supply from the internal auditory artery, which often branches off from the anterior inferior cerebellar artery or occasionally originates from the basilar artery directly. Within the facial canal, the petrosal branch of the middle meningeal artery and the stylomastoid artery both supply blood to the facial nerve. After the stylomastoid foramen, the main blood supply to the facial nerve is from a branch of the stylomastoid artery. Within the parotid gland, the facial nerve receives blood from the transverse facial artery and the superficial temporal artery, as well as one of either the occipital artery or the posterior auricular artery.[8]

Nerves

The course of the facial nerve axons inside the brainstem

The facial nerve is comprised of a motor root (containing motor fibers) and the nervus intermedius (containing sensory and parasympathetic fibers). The axons from the motor nucleus curve posteriorly around the abducent nucleus; they then pass through the facial colliculus of the floor of the fourth ventricle and, finally, emerge from the anterolateral brainstem. The nervus intermedius of the facial nerve also emerges from the anterolateral brainstem (pontomedullary junction).[6]

Segments of the facial nerve

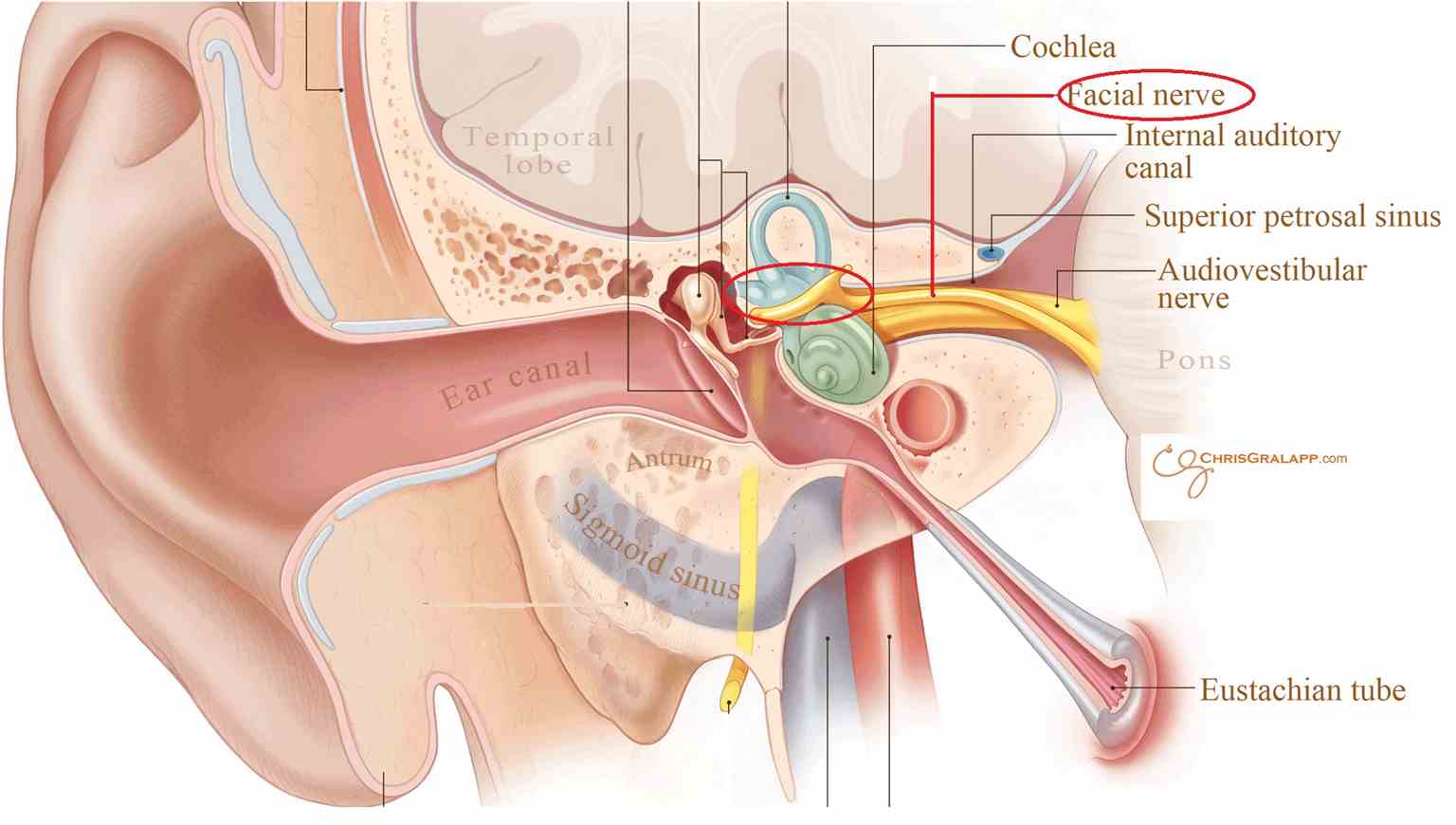

The first segment of the facial nerve is the intracranial/cisternal segment. This segment comprises the two roots of the nerve which emerge from the pons. The motor root and the nervus intermedius then pass through the posterior cranial fossa along with the vestibulocochlear nerve (VIII cranial nerve) at the cerebellopontine angle, finally entering the internal acoustic meatus in the temporal bone.

The second segment of the facial nerve is the meatal (canalicular) segment. This part of the facial nerve appears in the superior quadrant of the internal acoustic meatus.

The third part is the labyrinthine segment. This segment begins after the facial nerve has passed through the internal acoustic meatus. After the internal acoustic meatus, the motor root of the facial nerve and the nervus intermedius enter the facial canal, and they then pass between the cochlea and vestibule before bending posteriorly at the geniculate ganglion, at which point the motor root and nervus intermedius join. The labyrinthine segment gives off three branches: the greater superficial petrosal nerve (containing parasympathetic fibers for the lacrimal gland and taste fibers from the palate) and the external petrosal nerve.

The fourth segment of the facial nerve is the tympanic segment. The tympanic segment begins as the facial nerve passes posteriorly at the geniculate ganglion. This segment is in the medial wall of the middle ear cavity, directly below the lateral semicircular canal.

The fifth segment of the facial nerve is the mastoid segment. This segment begins after the tympanic segment moves downwards, distal from the pyramidal eminence of the middle ear cavity. From here, the mastoid segment travels through the facial canal and up to the stylomastoid foramen. This segment gives off three branches: the nerve to stapedius muscle, the chorda tympani (containing parasympathetic fibers to sublingual and submandibular salivary glands and taste fibers from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue), and the sensory branch, which joins the auricular branch of the vagus nerve. The sensory branch carries general somatic afferent fibers from the pinna and the external auditory meatus.

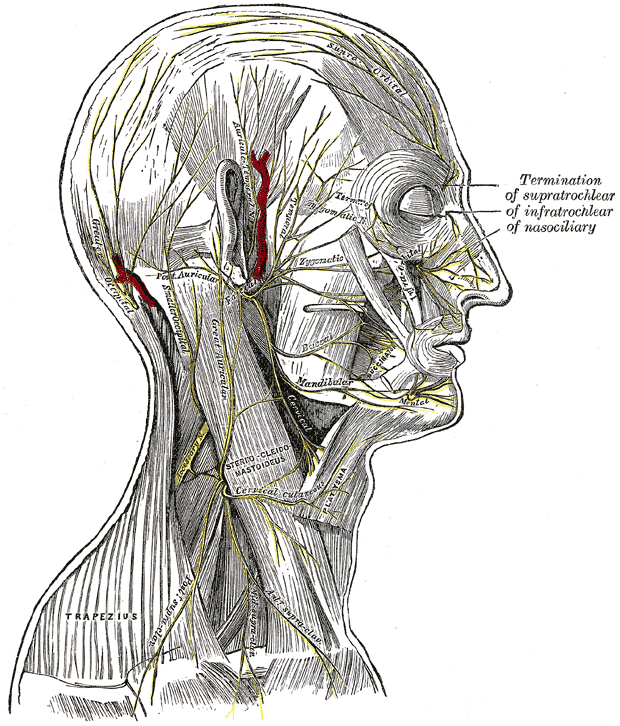

The final segment of the facial nerve is the extratemporal segment. This segment begins as the facial nerve exits the temporal bone through the stylomastoid foramen. After exiting, the facial nerve gives off two branches; the posterior auricular nerve (supplying the posterior auricular muscle, the superior auricular muscle, and the occipital belly of the occipitofrontal muscle) and the digastric nerve (supplying the posterior belly of the digastric muscle and the stylohyoid muscle). Next, this segment of the facial nerve enters the parotid gland. Within the parotid gland, the facial nerve gives off two main trunks. These are the superior temporofacial and inferior cervicofacial trunks. These two trunks give rise to the parotid plexus, and from this plexus, five branches emerge. These are known as the temporal (or frontal), zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical branches, which carry motor fibers to the facial muscles.[1][2][6][9]

Muscles

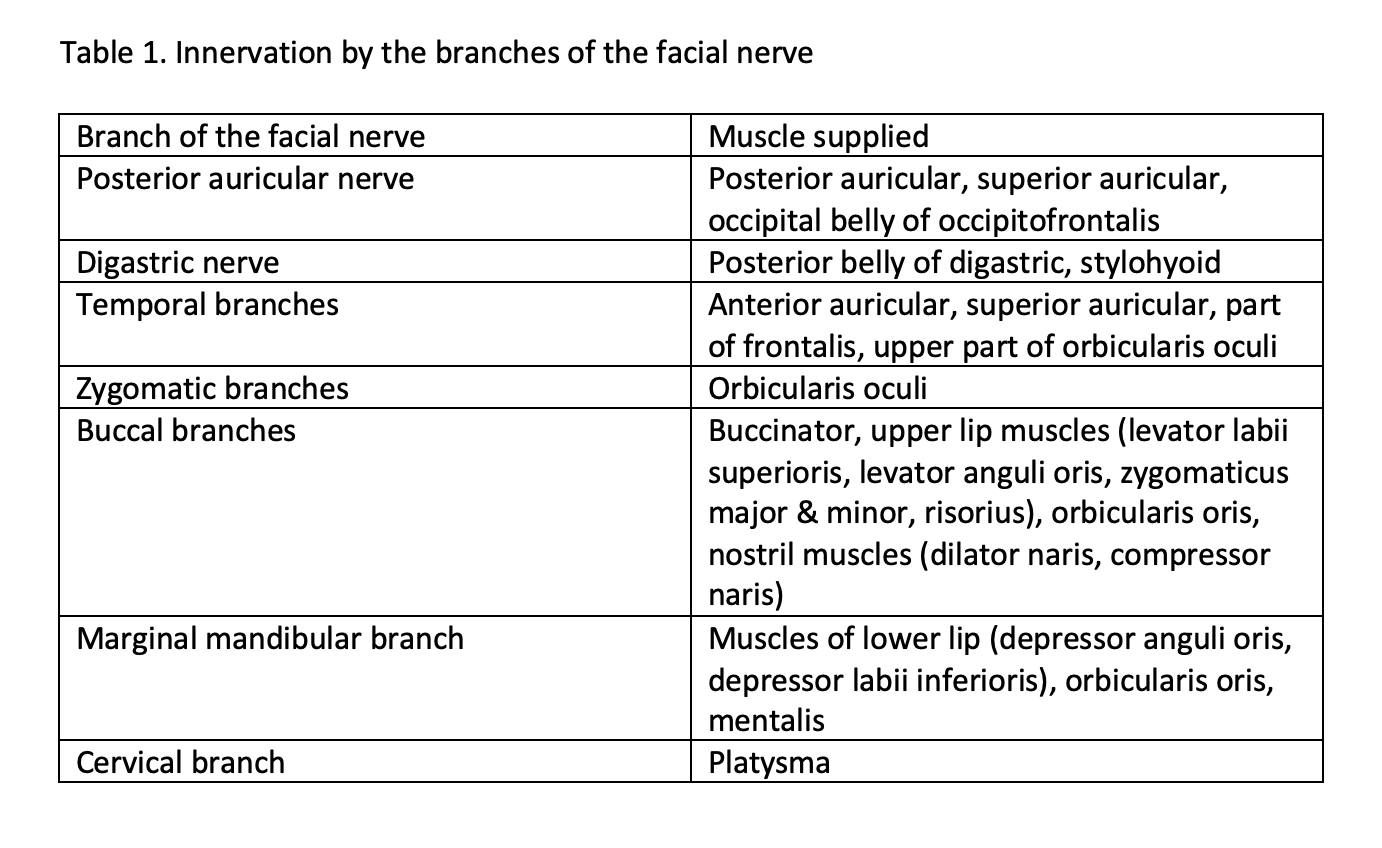

Essentially, all muscles of facial expression receive their innervation via the facial nerve. Table 1 summarizes these muscles and the corresponding nerves.[1][2]

Surgical Considerations

Acoustic Neuroma

An acoustic neuroma is a benign tumor of the myelin sheath of the vestibulocochlear nerve. As the facial nerve and vestibulocochlear nerve both lie in the internal auditory meatus, surgery to remove an acoustic neuroma can also potentially damage the facial nerve. A study based on microsurgery reported significant damage to the facial nerve requiring reconstruction in 6.6% of cases.[10]

Parotid Gland Surgery and Anesthesia

During parotid gland surgery, branches of the facial nerve may be damaged as the nerve branches off within the parotid gland. After parotid surgery, around 50% develop temporary facial weakness, while 7% end up with permanent facial palsy.[11] Also, an inferior alveolar nerve block during dental procedures may cause facial palsy if the injection goes too deep into the parotid gland.[1]

Cervicofacial Rhytidectomy ("Facelift")

Cervicofacial rhytidectomy may be performed in the subcutaneous plane, the deep plane, the subperiosteal plane, and the sub-superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) plane. As the facial nerve branches run below the SMAS plane, the deep plane technique, which necessitates the release of facial ligaments and tissue repositioning with suspension between the facial nerve branches, surgical dissection as performed using the deep plane facelift carries the highest risk of damage to branches of the facial nerve. The most commonly injured nerve during facelift surgery is the greater auricular nerve (a sensory nerve) and not the facial nerve. The greater auricular nerve should be marked before performing a facelift at the McKinney point, which is 6.5 cm caudal to the external acoustic meatus with the head turned 45 degrees. At this point, it crosses the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The commonest branch of the facial nerve that can suffer injury during a facelift is the buccal branch. Because of the collateral innervation demonstrated by the buccal branches, damage to the buccal branch is typically asymptomatic and, when seen, may show recovery over several months.

Clinical Significance

Upper Motor Neuron Lesions

Upper motor neuron lesions can be located either in the motor neuron in the precentral gyrus of the brain or along the course of the corticobulbar tract up to the second-order neuron in the pons. Causes of an upper motor neuron lesion include a stroke in the middle cerebral artery territory and space-occupying lesions along the pathway. Upper motor neuron lesions present as paralysis of the contralateral lower quadrant of the face, with sparing of the contralateral upper quadrant. Additional signs such as hemiparesis, dysphasia, and sensory deficits will depend on the other adjacent neural pathways and regions involved.[1]

Lower Motor Neuron Lesions in the Pons

Lower motor neuron lesions in the pons involving the motor nucleus can be the result of a range of pathologies such as stroke, neoplasia, and inflammation. Lower motor neuron lesions in the pons present as ipsilateral facial weakness involving the entire half of the face. Additional signs will depend on the other cranial nerve nuclei and nerve pathways in the vicinity affected by the pathological process. For example, several stroke syndromes, such as Foville syndrome and Millard-Gubler syndrome, which are characterized by ipsilateral facial palsy and contralateral hemiparesis accompanied by other cranial nerve involvement, have been described.[12] Moebius syndrome is a rare cause of congenital facial palsy due to hypoplasia of the facial motor nucleus. In this condition, the facial weakness is bilateral in 93% of patients, while 92% demonstrate bilateral eye abduction failure (6th cranial nerve involvement).[13]

Lower Motor Neuron Lesions after the Nerve Exits from the Brainstem

After its exit from the brainstem, clinical features of lower motor neuron lesions depend on which branches of the facial nerve are affected. If the motor axons of the facial nerve are affected, the result is facial muscle weakness. Damage to the nerve to stapedius results in hyperacusis; damage to the greater petrosal branch manifests as loss of lacrimation, and damage to the chorda tympani results in loss of taste from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue as well as the loss of function of the sublingual and submandibular salivary glands. Causes of lower motor neuron lesions beyond the brainstem include infections such as the herpes simplex virus (Bell's Palsy), varicella-zoster virus (Ramsay-Hunt syndrome), Lyme disease, and HIV, inflammatory conditions such as sarcoidosis, demyelinating conditions such as Guillain Barre Syndrome, vascular conditions such as hemifacial spasm due to neurovascular compression, trauma such as temporal bone fractures, and neoplasms (both benign and malignant).[14][1][2]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Takezawa K, Townsend G, Ghabriel M. The facial nerve: anatomy and associated disorders for oral health professionals. Odontology. 2018 Apr:106(2):103-116. doi: 10.1007/s10266-017-0330-5. Epub 2017 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 29243182]

Phillips CD, Bubash LA. The facial nerve: anatomy and common pathology. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2002 Jun:23(3):202-17 [PubMed PMID: 12168997]

Jenny AB, Saper CB. Organization of the facial nucleus and corticofacial projection in the monkey: a reconsideration of the upper motor neuron facial palsy. Neurology. 1987 Jun:37(6):930-9 [PubMed PMID: 3587643]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKUYPERS HG. Corticobular connexions to the pons and lower brain-stem in man: an anatomical study. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1958 Sep:81(3):364-88 [PubMed PMID: 13596471]

Gothard KM. The amygdalo-motor pathways and the control of facial expressions. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2014:8():43. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00043. Epub 2014 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 24678289]

Myckatyn TM, Mackinnon SE. A review of facial nerve anatomy. Seminars in plastic surgery. 2004 Feb:18(1):5-12. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-823118. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20574465]

Sataloff RT, Selber JC. Phylogeny and embryology of the facial nerve and related structures. Part II: Embryology. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2003 Oct:82(10):764-6, 769-72, 774 passim [PubMed PMID: 14606174]

BLUNT MJ. The blood supply of the facial nerve. Journal of anatomy. 1954 Oct:88(4):520-6 [PubMed PMID: 13211473]

Kochhar A, Larian B, Azizzadeh B. Facial Nerve and Parotid Gland Anatomy. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2016 Apr:49(2):273-84. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27040583]

Betka J, Zvěřina E, Balogová Z, Profant O, Skřivan J, Kraus J, Lisý J, Syka J, Chovanec M. Complications of microsurgery of vestibular schwannoma. BioMed research international. 2014:2014():315952. doi: 10.1155/2014/315952. Epub 2014 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 24987677]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSethi N, Tay PH, Scally A, Sood S. Stratifying the risk of facial nerve palsy after benign parotid surgery. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2014 Feb:128(2):159-62. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113003502. Epub 2014 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 24461039]

Onbas O, Kantarci M, Alper F, Karaca L, Okur A. Millard-Gubler syndrome: MR findings. Neuroradiology. 2005 Jan:47(1):35-7 [PubMed PMID: 15647948]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVerzijl HT, van der Zwaag B, Cruysberg JR, Padberg GW. Möbius syndrome redefined: a syndrome of rhombencephalic maldevelopment. Neurology. 2003 Aug 12:61(3):327-33 [PubMed PMID: 12913192]

Ho ML, Juliano A, Eisenberg RL, Moonis G. Anatomy and pathology of the facial nerve. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2015 Jun:204(6):W612-9. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13444. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26001250]