Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Pelvic Fascia

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Pelvic Fascia

Introduction

The pelvis is the base of the vertebral column; the sacrum is the center of the base. The vertebral column is not a real "column," as it is flexible and adaptable. It is composed of a series of rigid bodies connected to each other by flexible connective structures. It needs a solid base formed of the pelvis with the hips and the lower limbs, but the pelvis is not a real "base." The biomechanical model applied to biological structures, termed biotensegrity, includes an alternation and a network of compressed structures (bones) and tensile structures (ligaments and fascias). The bones of the skeleton are not considered rigid support structures, but instead, elements of compression are immersed within the spaces of a highly organized organization: the connective network of tension. The pelvic bones, including the sacrum, are suspended and immersed in this network of elastic tension structures of the fascia system.[1]

The result is the pelvis, an anatomical structure in dynamic equilibrium, capable of movement in space, within which the internal organs and vascular, nervous, and visceral structures can dwell and perform their function without interference. The fascia is the connective system, which is placed in the middle between the external anatomical structures and the internal visceral structures. The connective tissue purposes are to surround, protect, balance, defend, and nourish all the body’s structures.

At the pelvic level, clinicians can make a gross distinction between the external and the internal fascial system. The external system consists of the pelvic portion of the thoracolumbar fascia with its ligamentous thickenings and the perineal fascia system.[2] The internal system, the endopelvic fascia, is a little more complex, as the connective tissue is organized in peri-vascular bundles, supporting structures, and peri-muscular and peri-visceral layers.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

During pregnancy and childbirth, the pelvis adapts to the needs of the growth of the uterus and the child. It modifies its shape due to the balance between compression structures and tension structures. During the third trimester of pregnancy, the hormones influence the histological field of the connective tissue to allow the passage of the child.

There are different general functions of the fascia [3]. The dynamic linking function is its role in movement and stability; it is critical to myofascial force transmission and creates significant pretension in musculature due to its dense regular parallel ordered unidirectional connective tissue. The passive linking function is related to the portion of the fascia with a dense regular woven connective tissue with multidirectional parallel ordered fibers. It maintains continuity, static force transmission, and proprioceptive communication throughout the entire body. The fascia provides myofascial force transmission and proprioceptive feedback for movement control, maintains protection for nerves and vessels, and allows vascular sheaths to be in continuity with adventitia. The parietal and visceral fascia compartmentalize organs and body regions to maintain structural functions, promote sliding and reduce friction during motion, respond to stretch and distention, provide physical support, shock absorption, and limit the spread of infection.

The fascia tissue includes different collagen fibers, the hydrated extra-cellular matrix (ECM), and cells (fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, adipocytes, and various migrating white blood cells). The tissue structure and the molecular composition of ECM are directly correlated with the local mechanical forces. Many types of sensory neural fibers are present, suggesting that fascia contributes to proprioception and nociception, may be responsive to manual pressure, temperature, and vibration, and could influence some autonomic responses.

The pelvic fascias are a fundamental part of the body's bio-tensegrity system. The fascial tissue is the tension structure that makes it possible to balance the various bone components. It is a continuum that is histologically formed by collagen fibrils arranged irregularly and takes different names depending on the structures it covers.

The Thoracolumbar Fascia (TLF)

The posterior pelvic fascia is a portion of the thoracolumbar fascia. The thoracolumbar fascia (TLF) is an anatomical structure with complex histology, including elastic and muscular fibers within the extracellular connective tissue matrix (ECM). It is composed of fibrils arranged both in an irregular manner such as the bands and in a regular and flattened manner such as the aponeuroses.

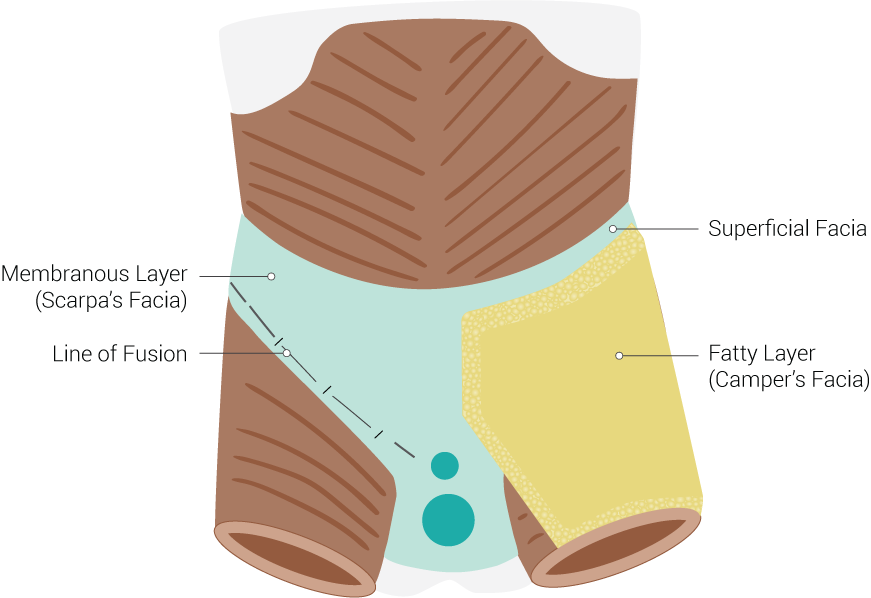

It is composed of several tissue layers located at different depths, which contain and separate the posterior paraspinal muscles from the posterior muscles of the anterior abdominal wall (psoas major and quadratus lumborum) continuing laterally in the fascia transversalis [2] toward the anterior abdominal area and the inguinal ligament. There are 3 layers: superficial (which consists of 2 sheets), the intermediate, and the deep. See Image. Fascial Layers.

The superficial layer is visible in the anatomical dissections as soon as the cutaneous and subcutaneous layer is removed. It has a rhomboid shape with its superior angle on the sixth thoracic level and the inferior on the coccyx. It is composed of two distinct sheets and is limited on its sides by the insertions of the dorsal muscles superior and superior gluteus inferiorly. The structural organization for the insertion of the dorsalis muscle is different from the thicker one dedicated to the insertion of the gluteus maximus: the fibers are also arranged differently as the 2 sheets merge below. On the midline, it has a reinforcement that inserts on the spinous apophyses of the vertebras and the interspinous ligaments of the thoracolumbosacral column from the sixth thoracic vertebra to the coccyx. It covers the paraspinal muscles posteriorly.

The intermediate layer of the TLF forms the retinaculum that envelopes and surrounds the paraspinal muscles; it continues with the deep sheet of the superficial layer. The retinaculum surrounds the long longitudinal muscles at the lateral and anterior side, inserting itself at the level of the vertebral transverse processes. Anteriorly, the fascia enters between the vertebral muscles and the quadratus lumborum (QL) muscle merging with its epimysium and connecting with the fascia of transversalis abdominis muscle.

The intermediate layer of TLF will form a lateral thickening resulting from the convergence of the three parts of the fascia from the paraspinal muscles posteriorly from the quadratus lumborum anteriorly and the lateral fascia transversalis.

At the top, this layer reaches the 12th ribs to which it attaches firmly, continuing in the thoracic region up to the cervical region, where it surrounds the anterior spinal muscles.

Inferiorly it continues in the iliolumbar ligaments and inserts itself on the iliac crest, and is in an anatomic relationship with the proximal course of the obturator nerve.

The deep layer of TLF is the anterior continuation of the intermediate layer that surrounds the QL muscle, interposing between it and the posterior aspect of the psoas major muscle.[4]

The two sheets of the superficial layer of the TLF merge at the level of the L5 through S1 lumbosacral passage, forming the composite band of the thoracolumbar fascia (TLC). Laterally, it inserts on the iliac crest together with the aponeurosis of the gluteus medius muscle, and, more medially, it enters on the posterior superior iliac posterior (SIPS) continuing inferiorly up to the lateral sacral tubercle and the ischial tuberosity. The iliolumbar, lumbosacral, and iliosacral ligaments are different regions of the same thoracolumbar fascia in which the direction of the fibers and the thickness of the fabric takes an individualized quality.

TLC is the structure that enters the posterior part of the fibrous capsule of the sacroiliac joint. The main ligaments are the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament and the sacrotuberous ligament.

The long dorsal iliosacral ligaments (LDL) connect the SIPS to the lateral sacral tubercles, limiting the sacral counternutation, or the anteriority of the iliac respective to the sacral base. They and the short sacroiliac dorsal ligaments are intertwined with the superficial portion of the interosseous ligament within the sacroiliac joint. The LDL is very solid and taut, and it can easily be taken for a bone structure during palpation. The tension in the long dorsal sacroiliac ligament can be increased by the loading on the ipsilateral sacrotuberous ligament and, to a lesser extent, during loading of the ipsilateral part of the erector spinae muscle. Traction to the gluteus maximus muscle can decrease tension.

LDLs continue inferiorly with the sacrotuberous ligaments, limiting the sacral nutation or the posteriority of the iliac respective to the sacral base. They continue anteriorly with the falciform ligament, which runs along the medial margin of the ischio-pubic branch toward the pubic symphysis, entering the formation of the Alcock canal of the pudendal nerve.

The sacrotuberous ligament is characterized by giving insertion to the gluteus maximus muscle, being in continuity with the insertion of the biceps femoris muscle, which inserts distally on the head of the fibula.

The sacrotuberous ligament can be tensioned by the sacral nutation, by the tension of the biceps femoris muscle during the pelvic tilt, by the contraction of the gluteus maximus and the piriformis muscles with which it is related, by other tensions coming from the thoracolumbar fascia.[5]

The iliolumbar ligaments are part of the middle layer of the TLF. They divide into an anterior and posterior portion, connecting the transverse apophysis of the fifth lumbar vertebra to the iliac crest. They form part of the anterior complex of the sacroiliac joint's fibrous capsule, thinner than the posterior complex formed by the TLC; they are formed by various fascicles that are inserted up to the iliopectineal line which defines the pelvic inlet.

The anterior sacroiliac ligament complex is completed by the sacrospinous ligament, which runs between the lateral aspect of the sacrococcygeal junction and the ischial spine. It does not appear to be part of the TLF due to its different embryonic origin, which is related to the ischiococcygeal muscle and the sacrococcygeal muscle that forms the posterior portion of the levator anis muscle.

The Endopelvic Fascia

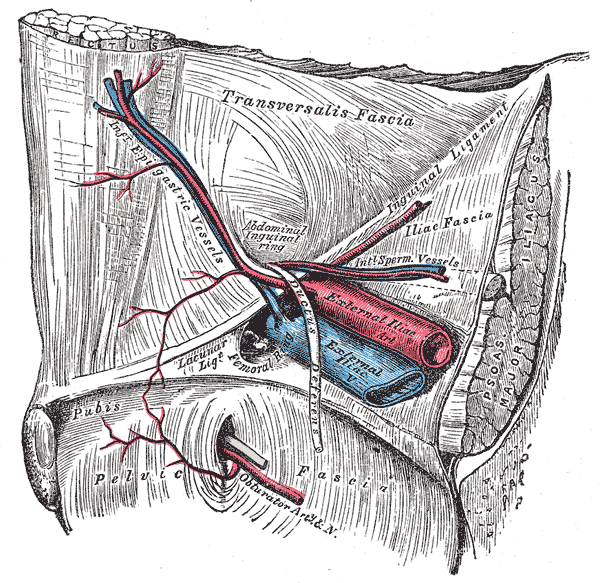

The endopelvic fascia can be subdivided into a parietal sheet, which medially covers the pelvic wall, and into a visceral sheet, which contributes to the suspension of the viscera. The pelvic fascia is composed of the fibro-areolar tissue surrounding the vascular and nerve pelvic vessels located in the subperitoneal space (see Image. Inferior Epigastric Artery and Vein).

The posterior parietal fascia is firmly adherent medially to the terminal portion of the anterior long ligament (ALL) lying on the front of the vertebral body from the fourth lumbar vertebra to the sacral periosteum.

It includes the muscular band of the piriformis and coccygeal muscles, continuing with that of the internal obturator muscle and the levator anis muscle, up to the pubic periosteum anteriorly. It is in continuity with the transversalis fascia located above and is intertwined with the periosteum of the iliac bone.

Anterior to the ischial spine, on the parietal endopelvic fascia, two thickening lines pass medially to the internal obturator muscle from the pubis to the ischial spine. The superior thickening is called the tendinous arch of the endopelvic fascia (ATFP). It is the insertion point of the deep perineal fascia (DPF). The inferior one is the tendon arch of the levator anis muscle (ATLA) on which the iliac portion of the levator anis muscle inserts.

In women, the visceral sheet of the endopelvic fascia is formed by two portions, one anterior and one posterolateral to the vagina.[6]

The DPF is the anterior part of the endopelvic fascia. It is a dense connective triangular structure located on a para-frontal plane stretched from the pubis anteriorly (except in the median posterior area of the symphysis pubis crossed by the urethra) to the tendinous arches of the endopelvic fascia bilaterally.

Posteriorly, it attaches medially at the annulus fibrosus surrounding the uterine cervix, which supports the isthmic segment of the uterus, and laterally at the anterior edge of the cardinal ligaments. The uterine arteries coming from the hypogastric arteries on the lateral pelvic wall run into the cardinal ligaments (or transverse cervical ligaments) to the myometrium beginning from the uterine isthmus. The deep perineal fascia is also called pubocervical fascia.

The deep perineal fascia supports the bladder posteriorly and forms the anterior vaginal wall, closing the anterior hiatus left by the pubovisceral and puborectal bundles of the levator anis muscle.

Anteriorly, the pubocervical fascia has reinforcements that weld it to the bladder's anterolateral aspect and are called pubovesical ligaments.

The posterior portion of the endo-pelvic fascia is the rectovaginal septum. It inserts inferiorly to the body of the perineum (the perineal body, or tendinous center of the perineum). It orients superior-dorsally, posterior to the posterior wall of the vagina of which also surrounds the lateral angles, to the fibrous ring of the uterine cervix, where it continues with the uterosacral ligaments.

The septum delimits anteriorly the peritoneal excavation of the Douglas passing then to the sides of the rectum to move toward the lateral aspect of the sacrum. The lateral parietal insertion of the rectovaginal septum is a fascial thickening present in the parietal pelvic fascia at the levator ani muscle level.

The cardinal ligaments (the ligaments of Meckelrodt) are properly one of those main connective structures of the endo-pelvic fascia that accompany the vascular pedicles. From the fibrous ring of the uterine isthmus, they firstly run lateral toward the ischiatic spine and then posteriorly going up the arterial course toward their origin at the hypogastric artery. The rectal and bladder wings complete the structures that the French authors call "sacro-recto-genito-vesico-pubic laminas" into which run the pelvic parietal and visceral arteries originated from the hypogastric artery.

The autonomic nervous pedicle coming from the hypogastric plexus, which is in a split of the posterior parietal pelvic fascia, runs along the caudal portion of the uterosacral ligaments, while vessels and fatty tissue occupy the cephalic one.

The uterosacral ligaments originate from the cervical fibrous ring (annulus fibrosus), together with the cardinal ligaments, head immediately backward without reaching the lateral wall, run at the sides of the rectum laterally to fit mainly on the fascia of the anus, coccyx, piriformis and internal obturator muscles and secondarily on the parietal endo-pelvic fascia (or pre-sacral).

Cardinal ligaments and uterosacral ligaments, together with the rectovaginal septum, sacral wings, and mesoureter, are part of the posterior portion of the endopelvic fascia, or posterior parametrium.

In the male, the Denonvilliers fascia (or rectovesical septum) surrounding the prostate posteriorly corresponds to the rectovaginal septum in the woman. The anterolateral prostatic fascia corresponds to the female pubocervical fascia.

The Perineum

The perineal area is the rhomboid-shaped pelvic outlet defined by the pubis, the coccyx, and the ischial tuberosities. It is anatomically divided into a posterior part and an anterior or urogenital portion. The anterior portion is covered by the layers of the superficial fascia of the perineum (or perineal fascia complex [PFC]): the perineal membrane and the perineal fascia, the posterior pelvic fascia (the TLF) continuing inferiorly.

The perineal membrane provides attachment for the superficial perineal muscles surrounding the deep transverse perineal muscle, limiting anterior-inferiorly the ischiorectal fossa. It is continuous with the ATLA and the endopelvic parietal fascia [7].

The perineal fascia is a continuity of the abdominal fascia and its deep layer component and covers the superficial perineal muscle (transverse superficial, bulbocavernosus, and ischiocavernosus muscles) and continues around the erectile bodies. The superficial layer of the perineal fascia is just below the skin of the perineum.

The perineal fascia complex inserts anteriorly on the pubis, laterally along the ischiopubic branches, and ends posteriorly in the ischiatic tuberosities. The back edge is free and combines the two left and right ischial tuberosities. The posterior superficial perineum does not have a superficial fascia that separates the cutaneous plane from the ischiorectal fossa, filled with adipose tissue at a different density.

The ischiorectal fossa continues anteriorly toward the pubis in the space between the perineal membrane and the deep perineal fascia, where the plane of the urethral sphincter and compressor is located.

The perineal body is a pyramidal-shape structure located between the anus and vulva. The perineal body provides insertion to the bulbocavernosus muscles, the superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles, a portion of levator ani muscles, and the rectovaginal fascia. Its apex is placed at the level of the lower middle third of the vagina, is attached to the rectovaginal fascia, and then to the uterosacral ligaments [8].

The Obturator Foramen

The obturator foramen (OF) is delineated by the ischial and pubic "rami" of the pelvis. It is covered by the internal and the external obturator muscles and their fascia. The fascia of the obturator foramen is the internal fascia of the external obturator muscle and the external fascia of the internal obturator muscle. The fascia of OF is a thickening sheet attached to the internal border of the foramen, crossed by the obturator nerve and vessels, joined to the fibrous ring of the acetabulum and the pubofemoral ligament of the hip. It is submitted to a perpetual succession of alternate tension due to the activity of the internal and external rotator muscles of the hip. This action could be important in maintaining the proper hydrostatic pressure and fluid flow into the ischiorectal fossa and the endopelvic spaces. The internal sheet of the internal obturator muscle fascia is part of the parietal endopelvic fascia that continues covering the piriformis and the coccygeus muscles and has a thickening on which the levator anis muscle is attached (ATLA) [9]. From a functional point of view, the hip is part of the pelvis and the pelvic floor.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply of the TLF is from the posterior parietal vessels of the torso. The endopelvic fascia placed above the levator anis muscles receives its blood supply from the parietal branches of the hypogastric vessels, the superior and the inferior gluteal arteries, while the pudendal vessels supply the portion of the endopelvic fascia situated below the levator anis muscles and the fascia of the perineum.[2]

Nerves

Histologically, the TLF is composed of collagen fibrils in which small vessels and contractile cells are present. The rich neuronal network includes free sensory terminations, mechanoreceptor (Golgi's receptor, Pacini and Paciniform receptors, Ruffini's receptor, and interstitial receptors) orthosympathetic branches from the dorsal spinal nerve following the blood vessels and that are part of the mechanosensory interoception. The innervation is from the posterior branch of the spinal nerves, from the sixth thoracic level downward. The endopelvic fascia receives nerve fibers from the lumbosacral plexus and the hypogastric plexus, the perineum from the pudendal nerve. The sensory nerve types of fascia link the fascia system to the nervous system, the immune system, the endocrine system, and regulate the muscle tone.[2]

Clinical Significance

The upper limit of the composite area of the thoracolumbar fascia (TLC) has an oblique course joining the spinous process of the fifth lumbar vertebra to the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS), superficially imitating the iliolumbar ligaments that are deeper [4]. The sacral rhomboid-shape area of Michaelis is interesting for obstetrics in evaluating the capacity of the pelvic inlet in shape and space. It is designed precisely on the composite area of TLF. The sacral diamond is subtended between the tip of the fifth lumbar vertebra's spinous process, the two posterior superior iliac spines, and the upper limit of the intergluteal sulcus. At the fascial level, they correspond to the upper limit of TLC and the long iliosacral dorsal ligaments (LDL). The shape of the sacral diamond area is influenced by the shape of the pelvic inlet and of the whole pelvis, as the pelvimetry science states. During the third trimester of pregnancy and childbirth, the hydration of fascia and ligaments permits more room in the pelvis for the passage of the child. During the gestation period, it enables the growth of the uterus, the maintenance of a correct body posture in static and dynamic, and permits a perfect balance between the diaphragm and the pelvic floor to maintain ideal breathing dynamic and a proper endoabdominal hydrostatic pressure. The mobility of the fascia tissues could be evaluated by the dynamic external pelvimetry that considers the range of motion between the SIPS and the sacrum and between the ischial tuberosities. The fascia and the ligaments of the pelvis have a nociceptive function relate to their stiffness, which can cause lumbopelvic pain and could impair the obstetric outcome.

The endopelvic fascia in all its segments exhibits estrogen receptors and relaxin, proving to have a hormone-dependent control of its forms and functions. The endopelvic and perineal fascia and ligaments are important factors for continence: trauma during childbirth can damage them and impair the pelvic visceral functions. In maintaining the urinary continence, the three anatomical separated layers of the pelvic floor operate as a single musculofascial tissue attached to the pelvis structure provides support to the viscera.

The deeper layer of the pelvic floor is the endopelvic fascia. It connects the vagina, the urethra, and the rectum to the sidewalls of the pelvis to each other. The fascia is strictly linked with the pelvic viscera and the levator ani muscle. Three functionally different parts of the endopelvic fascia sustain the distal, middle, and proximal portions of the vaginal hammock, as quoted by DeLancey’s model.[10]

The middle layer is the levator ani muscle, a muscle consisting of three parts: the iliococcygeus, puborectalis, and pubovisceralis (or pubococcygeus) muscles. The sling of the levator ani muscle (the puborectalis muscle) extends in a U shape from the pubic bone around the rectum, attaching to the vagina, urethra, and the perineal body. The puborectalis muscle lifts the anal canal, vagina, and urethra anteriorly and superiorly, augmenting their curvature leading to the continence function [11].

The outermost sheet of the pelvic floor is the layer of the superficial sphincters. It consists of the perineal membrane, the external and internal urethral sphincters, the bulbospongiosus and ischiospongiosus muscles, and the external anal sphincter. The external striated urethral sphincter is a semicircular ring, opened posteriorly, and it is attached to the perineal membrane and the lateral vagina walls. The rhabdosphincter carries two extensions: a short superolateral one (the compressor urethrae muscle) and a long inferolateroposterior extension (the urethrovaginal sphincter). The perineal membrane is a triangular fascial sheet that does not provide primary support to the pelvic viscera but avoids their excessive downward movement under the Valsalva’s maneuver and when the levator ani muscle is not contracted as during urination, defecation, and childbirth.

The pelvic floor and the diaphragm contract in advance when a voluntary movement of the limbs is planned to be started: it increases the intraabdominal pressure (IAP). IAP also increases during a laugh or a cough. The pelvic floor muscles close the pelvic canals to maintaining a distal pressure higher than the intravesical/intrarectal pressure. Connective tissues attaching the visceral fascia to the levator ani muscles as well as to the pubocervical (endopelvic) fascia create a firm platform that remains quite stable to counteract the downward force generated by the intraabdominal pressure.

The bio-mechanical tensegrity model is a functional model. Neither the muscle strength nor the intraabdominal pressure is sufficient to support the spine. However, due to this pressure, tension is created on the fascial system (abdominal wall, thoracolumbar fascia, and endopelvic/perineal fascia). This wall tension gives stability not only to the abdominal region but the back region as well. The pelvic floor and the diaphragm are essential to creating abdominal pressure. This can explain why many people with spine or pelvic problems also can have pelvic floor dysfunctions or breathing problems.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Inferior Epigastric Artery and Vein. This view depicts the external iliac vein and artery, obturator artery, pelvic fascia, and transversalis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Pardehshenas H, Maroufi N, Sanjari MA, Parnianpour M, Levin SM. Lumbopelvic muscle activation patterns in three stances under graded loading conditions: Proposing a tensegrity model for load transfer through the sacroiliac joints. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2014 Oct:18(4):633-42. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.05.005. Epub 2014 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 25440220]

Willard FH, Vleeming A, Schuenke MD, Danneels L, Schleip R. The thoracolumbar fascia: anatomy, function and clinical considerations. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec:221(6):507-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01511.x. Epub 2012 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 22630613]

Zügel M, Maganaris CN, Wilke J, Jurkat-Rott K, Klingler W, Wearing SC, Findley T, Barbe MF, Steinacker JM, Vleeming A, Bloch W, Schleip R, Hodges PW. Fascial tissue research in sports medicine: from molecules to tissue adaptation, injury and diagnostics: consensus statement. British journal of sports medicine. 2018 Dec:52(23):1497. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099308. Epub 2018 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 30072398]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchuenke MD,Vleeming A,Van Hoof T,Willard FH, A description of the lumbar interfascial triangle and its relation with the lateral raphe: anatomical constituents of load transfer through the lateral margin of the thoracolumbar fascia. Journal of anatomy. 2012 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 22582887]

Aldabe D, Hammer N, Flack NAMS, Woodley SJ. A systematic review of the morphology and function of the sacrotuberous ligament. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2019 Apr:32(3):396-407. doi: 10.1002/ca.23328. Epub 2019 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 30592090]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLarson KA, Luo J, Yousuf A, Ashton-Miller JA, Delancey JO. Measurement of the 3D geometry of the fascial arches in women with a unilateral levator defect and "architectural distortion". International urogynecology journal. 2012 Jan:23(1):57-63. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1528-7. Epub 2011 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 21818620]

Stein TA, DeLancey JO. Structure of the perineal membrane in females: gross and microscopic anatomy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008 Mar:111(3):686-93. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318163a9a5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18310372]

Lefevre R,Davila GW, Functional disorders: rectocele. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2008 May; [PubMed PMID: 20011409]

Tunn R, Delancey JO, Howard D, Ashton-Miller JA, Quint LE. Anatomic variations in the levator ani muscle, endopelvic fascia, and urethra in nulliparas evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Jan:188(1):116-21 [PubMed PMID: 12548204]

Ashton-Miller JA, DeLancey JO. Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007 Apr:1101():266-96 [PubMed PMID: 17416924]

Delancey JO, Ashton-Miller JA. Pathophysiology of adult urinary incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2004 Jan:126(1 Suppl 1):S23-32 [PubMed PMID: 14978635]