Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is the most common form of pediatric scoliosis. It occurs in individuals between the ages of 10 to 18. By definition, idiopathic scoliosis implies that the etiology is unknown or not related to a specific syndromic, congenital, or neuromuscular condition. Treatment options include conservative management, bracing, or operative intervention.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Idiopathic scoliosis is a diagnosis of exclusion of other forms of scoliosis. As of today, there is no identifiable cause for idiopathic scoliosis. Theories include hormonal causes, asymmetric growth, muscle imbalance, and genetic factors. Nearly 30% of patients with AIS have a family member with scoliosis.

Epidemiology

The prevalence is about 1% to 3% for AIS. There is a preference for females and a right-sided curvature. To be considered for the classification of scoliosis the curve must be at least 10 degrees in the coronal plane. The prevalence is approximately 0.1% for curves measuring more than 40 degrees (those which tend to be those requiring operative intervention).

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical is warranted. Particular attention should be paid to the developmental history to rule out any other etiologies of scoliosis. Attention must also be placed on questions focused on skeletal maturity including the age of menarche and determination of Risser classification. In a gross generalization, most adolescent patients presenting with idiopathic scoliosis will not have dramatic back pain from the curvature. Many tend to be very active including athletes, cheerleaders, and otherwise very healthy children.[4][5][6]

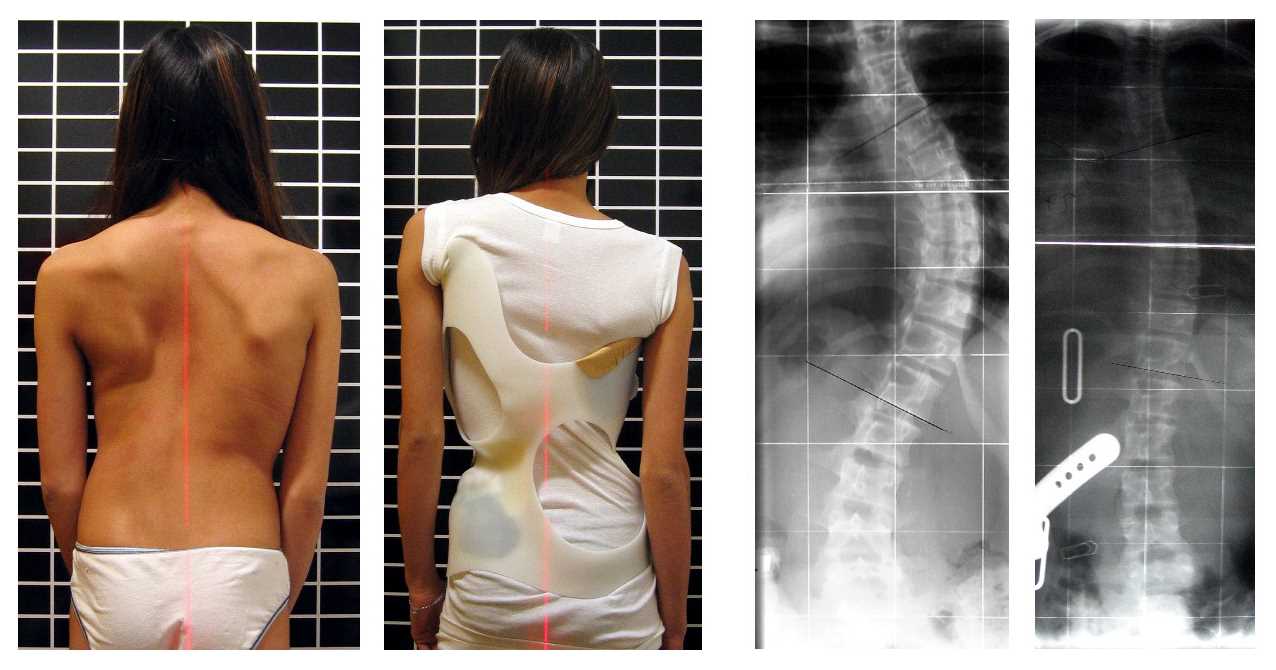

The physical exam must include a neurologic assessment as well as evaluation of the curve’s shape, form, and flexibility. Patient privacy and sensitivity in this age demographic are important to consider while ensuring proper evaluation of the spinal curve. Photographic documentation with the patient standing upright as well as bending over is vital to track progression as well as the operative outcome. Spinal curvature is not isolated to a spinal deformity. Rib prominence, waistline, and shoulder height should also be documented.

Evaluation

Evaluation is generally a screening evaluation either through a school entity, sports coach, or pediatrician. The proper formal evaluation includes x-ray imaging. Patients need a standing coronal x-ray, sagittal x-ray, left and right bending x-rays. Risser classification can generally be calculated from the iliac crest on the coronal x-ray platform. Consensus holds that a CT scan and MRI imaging for typical AIS patients is not warranted. However, certain intraoperative imaging guidance techniques do require either preoperative or intraoperative CT imaging. This is a surgeon and technology specific. Patients who are pre-operative candidates undergo a standard laboratory workup including CBC, BMP, INR/PTT, urinalysis, and a urine pregnancy test for all females.

Other tests should include pulmonary function tests.

Treatment / Management

Historically speaking, those with curves less than 10 degrees do not meet the specification for diagnosis of AIS. Furthermore, the US Preventative Services Task Force has recently questioned whether school screenings positively impact the patient-centered-health outcomes.[7][8][9]

Generally speaking, those with curves of 10 to 25 degrees are monitored for surveillance with serial x-rays. This is usually at 3, 6 or 12-month intervals.

Those with curves greater than 25 degrees but less than 40 to 45 degrees are candidates for bracing. The Bracing in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Trial (BrAIST) was an NIH funded randomized control trial that illustrated the effectiveness of bracing in the adolescent population. Even though braces are widely prescribed, these uncomfortable devices have low compliance rates and their overall success remains questionable. Questions have been raised about every type of brace for managing scoliosis.

Those with curves over 40 to 45 degrees who are skeletally immature are operative candidates. The mainstay of operative treatment is surgical fusion. Historically this could be anterior or posterior fusion or a combined anterior-posterior approach. Currently, the leading technique is posterior fusion with pedicle screws and bilateral rod placement. Selection of operative levels is a complex decision algorithm taking into account coronal deformity location, regional kyphosis, shoulder height, L4 tilt, and lumbar alignment. Furthermore, a ratio comparison between the main thoracic curve Cobb angle and the thoracolumbar curve Cobb angle as well as the apical vertical translation and apical vertebral rotation must be considered for advanced operative planning.

New non-fusion techniques such as tethering procedures are gaining traction as well. Surgery for scoliosis is a major procedure and the literature is replete with serious complications that are even more disabling than the disorder itself.

Other treatments like physical therapy, electrical stimulation, nutrition, and spinal manipulation have not been found to be effective in managing scoliosis.

These are gross generalizations, and actual patient care operative decisions must account for patient-specific factors, skeletal maturity, deformity progression, patient’s socioeconomic factors, and surgeon experience.

Differential Diagnosis

It is essential to rule out scoliosis from other causes such as neurologic conditions, neuromuscular conditions, congenital, or syndromic issues.

Staging

The Lenke Classification scheme best categorizes staging. The purpose of this classification scheme is to create a uniform approach to naming and described curves. The overall intent at an advanced level is also to give some preference for the operative treatment protocol.

The Lenke Classification takes into account the coronal curve (1-6), the sagittal deformity (-, N, or +), and the lumbar spine modifier (A, B, C). This creates a descriptor such as 3C+ or 1B-. Formal education of the Lenke classification and memorization of the criteria is beyond the scope of this text. However, it is the preferred method for spinal deformity surgeons to communicate about AIS.

Prognosis

Patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis that go untreated into adulthood can have a rate of progression that is approximately 0.5 to 1 degree per year once the patient has reached a 50-degree coronal angle. Furthermore, in gross generalization, curves in adulthood tend to be much stiffer and more rigid than in the adolescent cohort requiring more aggressive and invasive surgical techniques.

Long term studies report a higher rate of arthritis and poor perception of body image in patients with scoliosis, irrespective of treatment. Further, if the surgical correction involves chest wall invasion, it may also result in pain and decreased lung function.

Complications

Complications from untreated scoliosis include deformity progression. This can generate back pain, lumbar radiculopathy, cosmetic problems, nerve damage, and even cardiac and pulmonary restriction. Untreated patients with a curve of more than 80 degrees in the coronal plane can have increased shortness of breath.

Surgical complications are generally lower than in adult spinal deformity surgery but present. One national data series estimated the post-surgical neurologic injury at 0.9%, respiratory complications at 2.8%, cardiac complications at 0.8%, infection at 0.5%, and 2.7% for gastrointestinal complications. Delayed infections in the hardware are also common.

Surgeon expertise and volume of surgery are also important factors regarding the outcome and cost of surgery.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients are managed in an ICU following surgery and depending on the extent of surgery, some require a prolonged stay.

Most patients undergoing adolescent idiopathic scoliosis surgery are expected to return to home following their operative intervention. Length of stay can vary based on the surgical procedure, surgeon preference, institutional algorithms, and other medical or socioeconomic sequel. Bracing is generally not needed as a post-operative therapy.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Challenges do present in the management of bracing with this population. Furthermore, a study has illustrated improved outcomes with increased compliance to bracing protocols. Adherence requires significant involvement from both the patient and the patient’s support structure. Furthermore, significant education of the parents is required regarding operative risk, operative planning, and purpose of the operative intervention.

Pearls and Other Issues

- The Lenke Classification creates the language used by experts to converse about scoliosis type. It is the most common and widely used classification scheme.

- To properly classify adolescent idiopathic scoliosis proper imaging is essential.

- Significant research is ongoing regarding the genetic factors related to curve formation and progression.

- Management of this disease etiology requires patient as well as parent education to maximize outcome and create reasonable expectations.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of scoliosis is complex and the overall results are poor. Because the condition results in a cosmetic and functional deformity it is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes a physical therapist, orthopedic surgeon, pulmonologist, rheumatologist and a neurologist. The vast majority of patients do not require surgery and can be managed with non-surgical therapies.

While braces are heavily prescribed, they have low compliance because of the extreme discomfort. For those with functional deficits, physical therapy is recommended - this therapy has no impact on scoliosis - it just improves muscle and joint function. After surgery, nurses should encourage and educate patients regarding incentive spirometry to prevent atelectasis.

Surgery is recommended for symptomatic patients with severe deformity-but the patient needs to be educated about the complications of scoliosis which are not trivial. After surgery, nurses should encourage incentive spirometry to prevent atelectasis. Surgery can improve function and aesthetics but a significant number of patients do remain with residual pain or other neurological deficit that can reduce the quality of life.[7][10][11]

A mental health nurse should consult with all patients because scoliosis can impart serious cosmetic deficits which lead to anxiety, withdrawal, and depression. Most patients with scoliosis do not take part in sports for fear of embarrassment or humiliation.

Some degree of pain is present in patients with scoliosis but the key is not to empirically prescribe prescription-strength pain medications. Many other modalities for pain control like TENS, acupuncture, stretching, exercise, and yoga can help.

Outcomes

Overall the outcomes after surgery are not satisfactory; the surgery is often associated with severe complications that are worse than scoliosis itself. In addition, many patients have low self-esteem because of the spinal defect and remain isolated and withdrawn. The interprofessional team should take steps to ensure that they do not offer invasive treatments that are more likely to do more harm than good; the key is to improve the quality of life.[12][13][14] (Level V)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

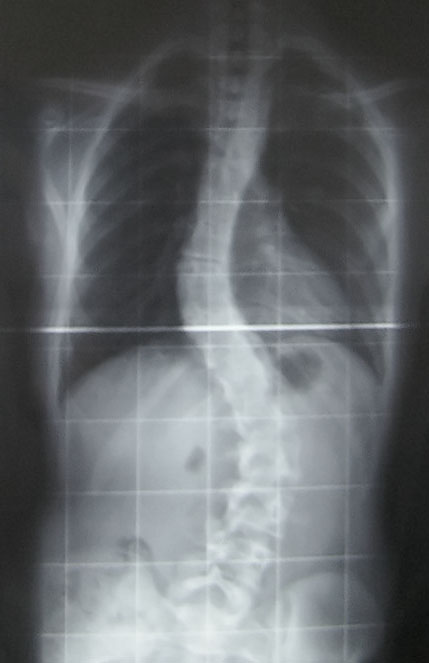

This is an posterior-to-anterior X-ray of a case of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis - specifically, my spine. There is a thoracic curve of 30° and a lumbar curve of 53° (Cobb angle - see scoliosis). This was taken at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital. The largest curve (53°) is of a magnitude typically near the lower surgery boundary, although many factors decide whether surgery is necessary on a scoliosis case. Contributed by Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain)

References

Fruergaard S, Ohrt-Nissen S, Dahl B, Kaltoft N, Gehrchen M. Neural Axis Abnormalities in Patients With Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Is Routine Magnetic Resonance Imaging Indicated Irrespective of Curve Severity? Neurospine. 2019 Jun:16(2):339-346. doi: 10.14245/ns.1836154.077. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30653908]

Pepke W, Almansour H, Lafage R, Diebo BG, Wiedenhöfer B, Schwab F, Lafage V, Akbar M. Cervical spine alignment following surgery for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS): a pre-to-post analysis of 81 patients. BMC surgery. 2019 Jan 15:19(1):7. doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0471-2. Epub 2019 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 30646880]

Zhu H, Li B, Jian Y, Sun Z, Yang Z. [Effectiveness analysis of Lenke type 1 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis with different proximal fixation vertebra]. Zhongguo xiu fu chong jian wai ke za zhi = Zhongguo xiufu chongjian waike zazhi = Chinese journal of reparative and reconstructive surgery. 2019 Jan 15:33(1):41-48. doi: 10.7507/1002-1892.201808015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30644259]

Yagci G, Yakut Y. Core stabilization exercises versus scoliosis-specific exercises in moderate idiopathic scoliosis treatment. Prosthetics and orthotics international. 2019 Jun:43(3):301-308. doi: 10.1177/0309364618820144. Epub 2019 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 30628526]

Levi D, Springer S, Parmet Y, Ovadia D, Ben-Sira D. Acute muscle stretching and the ability to maintain posture in females with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation. 2019:32(4):655-662. doi: 10.3233/BMR-181175. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30636726]

van den Bogaart M, van Royen BJ, Haanstra TM, de Kleuver M, Faraj SSA. Predictive factors for brace treatment outcome in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a best-evidence synthesis. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2019 Mar:28(3):511-525. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-05870-6. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30607519]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 30601360]

Grabala P, Helenius I, Buchowski JM, Larson AN, Shah SA. Back Pain and Outcomes of Pregnancy After Instrumented Spinal Fusion for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. World neurosurgery. 2019 Jan 3:():. pii: S1878-8750(18)32929-2. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.106. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30610987]

Le Berre M, Pradeau C, Brouillard A, Coget M, Massot C, Catanzariti JF. Do Adolescents With Idiopathic Scoliosis Have an Erroneous Perception of the Gravitational Vertical? Spine deformity. 2019 Jan:7(1):71-79. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.05.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30587324]

Farooqui SI, Siddiqui PQR, Ansari B, Farhad A. Effects of spinal mobilization techniques in the management of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis - A meta-analysis. International journal of health sciences. 2018 Nov-Dec:12(6):44-49 [PubMed PMID: 30534043]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLonstein JE. Selective Thoracic Fusion for Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Long-Term Radiographic and Functional Outcomes. Spine deformity. 2018 Nov-Dec:6(6):669-675. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.04.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30348342]

Chang DG, Suk SI, Kim JH, Song KS, Suh SW, Kim SY, Kim GU, Yang JH, Lee JH. Long-term Outcome of Selective Thoracic Fusion Using Rod Derotation and Direct Vertebral Rotation in the Treatment of Thoracic Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: More Than 10-Year Follow-up Data. Clinical spine surgery. 2020 Mar:33(2):E50-E57. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000833. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31220038]

Diebo BG, Segreto FA, Solow M, Messina JC, Paltoo K, Burekhovich SA, Bloom LR, Cautela FS, Shah NV, Passias PG, Schwab FJ, Pasha S, Lafage V, Paulino CB. Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis Care in an Underserved Inner-City Population: Screening, Bracing, and Patient- and Parent-Reported Outcomes. Spine deformity. 2019 Jul:7(4):559-564. doi: 10.1016/j.jspd.2018.11.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31202371]

Weinstein SL. The Natural History of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2019 Jul:39(Issue 6, Supplement 1 Suppl 1):S44-S46. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001350. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31169647]