Introduction

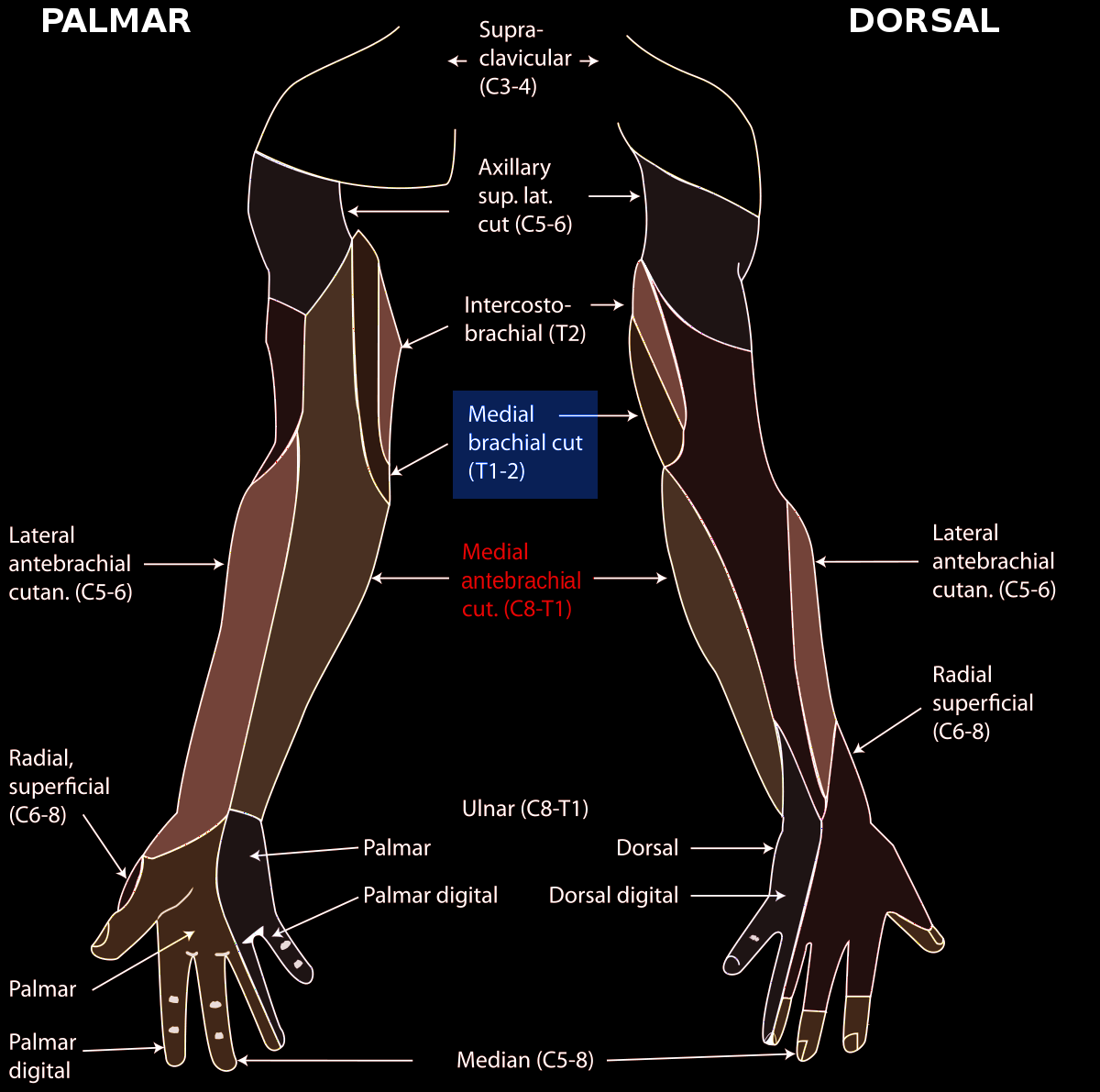

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, along with the posterior and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerves, is responsible for providing sensation to the skin of the forearm.[1] Specifically, the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve provides sensory innervation of the medial forearm as well as the skin overlying the olecranon.[2]

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve emerges from the medial cord of the brachial plexus and has sensory cell bodies located in the dorsal root ganglia of C8 and T1. The nerve travels distally along the upper arm running through the brachial fascia along with the basilic vein approximately 10 cm proximal to the medial epicondyle. As the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve exits the brachial fascia, it divides into two major branches, anterior and posterior, which continue distally to the wrist.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The sensory innervation of the skin of the back, shoulder, and upper limb is divided into the paravertebral skin — located approximately three inches on either side of the dorsum of the back. This area is innervated by the dorsal primary ramus of the mixed spinal nerves. The rest of the somatic area innervated by a single spinal nerve is supplied by the ventral ramus of the mixed spinal nerve from a dorsal root ganglion.

The sensory functions of the skin of the upper limb are derived from neuronal cell bodies located in the dorsal root ganglia from C5 to T1. At each level, the (sensory) dorsal and (motor) ventral roots unite to form a mixed spinal nerve, which has a dorsal primary ramus and a ventral primary ramus (Latin for "branch").

Role of the Dermatome in the Sensory Innervation of the Upper Limb

Each dorsal root ganglion innervates a dermatome (Latin from Greek = skin cuts). The C5 dermatome is located over the skin of the shoulder, extending down the lateral aspect of the arm. The C6 dermatome extends over the lateral aspect of the forearm, extending over the ventral aspect of the medial thumb and the lateral aspect of the index finger. The middle finger occupies the C7 dermatome, which begins more medially than the C6 dermatome in a laminar fashion. The C8 dermatome passes over the more medial lamina than the C7 dermatome. As it passes down the ventral arm and forearm, the C8 dermatome innervates the ventral aspect of the ring and little finger, extending down from the elbow. The T1 dermatome supplies the medial aspect of the arm. The dermatomes are also present posteriorly in a manner that corresponds to the ventral aspect of the forearm.

One important aspect is that the dermatomes that supply the arm and forearm also cross the wrist and innervate the hand. By contrast, the peripheral nerve territories that supply the forearm – the medial, lateral, and posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerves - do not cross the wrist. This distinction is very important in the clinical diagnosis and localization of peripheral neuropathies.

Neurological lesions can be divided into those which involve a nerve root (radiculopathy – from the Latin radix = root). Another group of lesions involves the brachial plexus (see below). These are termed plexopathies. Both of these clinical entities will exhibit a loss of sensation corresponding to one or more dermatomes.

By contrast, peripheral nerve lesions (neuropathies) involve peripheral nerves. These do NOT follow a dermatomal pattern of loss of sensation (anesthesia). Rather, they have a pattern peculiar to each peripheral nerve. For example, a lesion that provides anesthesia over the medial aspect of the ring finger and all of the little finger is caused by an ulnar nerve lesion. The area proximal to this lesion is supplied by the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm, not the ulnar nerve.

A lesion that seems to be similar in the area of anesthesia would involve loss of sensation over the entirety of the ring and little fingers. This lesion also involves the medial forearm. This is an example of a C8 dermatome. This lesion can be a C8 radiculopathy or part of a lower brachial plexus lesion that involves C8.

Another distinction involves loss of motor function, which can be part of these syndromes. Those which innervate the musculature in a segmental fashion (similar to the dermatomes) are termed myotomes. An important distinction is that the dermatomes follow a superior-to-inferior orientation on the upper limb, while the myotomes are oriented proximally to distally. Thus, the shoulder muscles are innervated by the upper portion of the brachial plexus (e.g., C5 and C6). The intrinsic muscles of the hand are innervated by the lower portions of the brachial plexus (C8, T1).

An important concept is that damage to a neurological structure, such as radiculopathy, plexopathy, or neuropathy, can damage the fine touch fibers, causing loss of sensation. However, the pain fibers may remain active or even become hyperactive (hyperalgesia - Greek excess plus pain). The pain axons survive because they are much smaller and have much lower metabolic demands than the much larger fine-touch fibers. The result of loss of sensation for fine touch in the presence of normal or hyperactive pain sensation is termed paresthesia. The hyperalgesia (increased pain sensation) is often more disturbing to the patient than the loss of fine touch sensation.

The Brachial Plexus

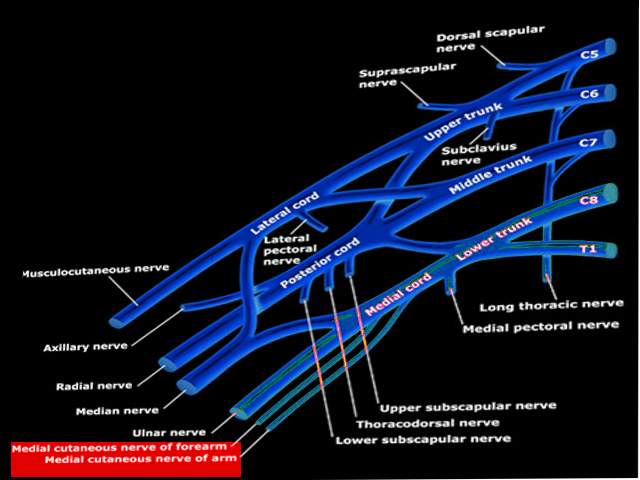

The brachial plexus is formed from the ventral rami of C5-T1 spinal segments and supplies the peripheral nerves that innervate the upper limb. Each spinal segment is formed from a dorsal root (sensory function with cells in the dorsal root ganglion at each level) and a motor ventral root (with motor neurons located in the ventral horn of the spinal cord). The dorsal and ventral roots unite to form a mixed spinal nerve, which then subdivides into a dorsal primary ramus that innervates the paravertebral muscles and skin) and the ventral primary root (that innervates the anterolateral muscles and skin).

An area of confusion is that the spinal cord has roots that emerge from the spinal cord. The ventral primary ramus at each level forms the roots of the brachial plexus (which are not the roots of the spinal cord).

The brachial plexus contains roots, trunks, divisions, cords, and branches.[3] The C5 nerve root is formed from the C5 ventral ramus. The C6 root of the brachial plexus is formed from the C6 ventral ramus, and so on. The C5 and C6 roots unite to form the superior (upper) trunk of the brachial plexus. C7 continues as the middle trunk. C8 and T1 combine to form the inferior (lower) trunk of the brachial plexus.

Each trunk then divides into anterior and posterior divisions. The anterior divisions innervate the musculature of the anterior part of the upper limb. Such muscles are generally flexors such as the biceps brachii, brachialis, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus. The posterior divisions innervate the posterior musculature of the upper limb. Such muscles are generally extensors of the upper limb, such as the triceps brachii, brachioradialis, and the muscles whose name contains the word extensor.

Two cords are derived from the anterior divisions – the lateral cord (C5, C6, C7) and the medial cord (C8, T1). Generally, the muscles derived from the lateral cord lie more proximally than those from the medial cord. One cord is derived from the posterior divisions – the posterior cord (C5, C6, C7, C8, T1).

Concerning the cutaneous innervation of the arm (brachium), four cutaneous nerves innervate the arm. The medial cord gives rise to the medial brachial cutaneous nerve (medial cutaneous nerve of the arm), which arises near the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve (medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm), which arises just distal to the medial brachial cutaneous nerve. The posterior cord gives rise, via the axillary nerve, to the superior (upper) lateral brachial cutaneous nerve. The posterior cord also gives rise to the inferior (lower) lateral brachial cutaneous nerve via the radial nerve. The posterior cord also gives rise to the posterior brachial cutaneous nerve via the radial nerve.

Concerning the cutaneous innervation of the forearm (antebrachium), there are 3 nerves. The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve innervates the medial forearm but does not cross the wrist. The lateral cord of the brachial plexus gives rise to the musculocutaneous nerve, which innervates the BBC muscles – the biceps brachii, brachialis, and coracobrachialis. The musculocutaneous nerve then forms the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The territory of this lateral forearm nerve ends at the wrist, as none of the sensory nerves of the forearm cross the wrist.

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is one of three non-terminal branches of the medial cord, which is the continuation of the anterior division of the inferior trunk of the brachial plexus. The other two non-terminal branches of the medial cord are the medial brachial cutaneous nerve, which provides sensory innervation for the medial arm, and the medial pectoral nerve, which provides motor innervation to the pectoralis major and minor. The medial cord also contributes fibers to the median nerve and ultimately continues distally as the ulnar nerve.[4]

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve can be found superficial to the axillary artery and vein within the axillary fossa, near the median and ulnar nerves.[5] As this nerve courses distally, it accompanies the basilic vein as it crosses between the triceps brachii and brachialis muscles. The nerve then enters the brachial fascia overlying the biceps brachii, and runs at the ulnar side of the brachial artery. From there, the nerve runs with the basilic vein at the level of the elbow, where it ultimately divides distally to the elbow into the volar and ulnar branches, which provide sensory innervation to the medial forearm and skin of the olecranon.[2][3]

With respect to the hand, the sensory cutaneous branch of the radial nerve innervates the dorsum of the thenar web and the posterior portion of the thumb. The median nerve innervates the medial thumb, the lateral side of the index finger, the medial side of the index finger, the lateral side of the middle finger, the medial side of the middle finger, and the lateral side of the ring finger. The ulnar nerve innervates the medial side of the ring finger, both sides of the little finger, and the hypothenar eminence.

Embryology

In the fifth week of development, the limb buds derived from mesoderm grow outward from the developing embryo. The brachial plexus is derived from the ectoderm. Thus the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve forms as the segmental nerves from the spinal cord penetrate these limb buds.[3]

The brachial plexus originates from the fifth through eighth cervical segments, as well as the first thoracic segment. Two branches of the brachial plexus emerge — one dorsal branch that innervates extensor muscles and one ventral branch that innervates flexor muscles. Growth factors like homeobox (Hox) genes, sonic hedgehog (SHH), and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) aid in the positioning of the limbs at birth. Homeobox genes help in proximodistal limb patterning, Sonic hedgehog signaling molecules regulate limb growth, and fibroblast growth factors assist in anterior-posterior limb patterning.[3]

Nerves

The anterior and posterior branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve usually appear at the level of the medial and lateral epicondyles.[1] The anterior branch gives off 7 to 10 secondary branches and is primarily distributed in the middle one-third of the anterior medial forearm. The posterior branch gives off 10 to 12 secondary branches, primarily distributed in the proximo-medial region of the posterior forearm.[1] In addition to the two major branches, several cutaneous branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve have been identified, and all emerge medially, coursing away in an anterolateral direction.[6]

Physiologic Variants

Several variations have been reported in the anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and its branching pattern. There are cases where the nerve itself arises from the inferior trunk of the brachial plexus instead of the medial cord.[7] The posterior branch is highly variable as reports have described an anastomosis between it and the ulnar nerve as well as its palmar cutaneous branch, the medial brachial cutaneous nerve, and the posterior antebrachial cutaneous nerve.[2]

Another variation exists in which the described four medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve branches emerge before the separation into anterior and posterior branches. These branches travel to the medial, distal region of the upper arm, which is an area normally innervated by the medial brachial cutaneous nerve.[2]

Surgical Considerations

Understanding the anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is important in transplant surgery using forearm flaps as donor tissue. Recipient tissues for such flaps have included the mouth, penis, and hands. Thus, successful sensory recovery for these areas relies on knowledge of the cutaneous innervation of the donor tissue.[1] One such example is forearm free-flap phalloplasty. This surgical technique is used in transgender surgeries to create a neophallus. The flap involved in this procedure contains the skin of the anterior forearm and much of the surrounding tissue, including the medial and lateral cutaneous nerves of the forearm.[8] The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve itself can also be used in surgical grafts and is frequently used in brachial plexus reconstructions.[9]

Posterior branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve cross the ulnar nerve, normally 2 cm distal to the medial epicondyle. They are, therefore, at risk of damage during ulnar nerve releases at the elbow to treat cubital tunnel syndrome. Complications of damage to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve in such procedures include hyperesthesia and hyperalgesia, as well as painful neuromas.[10][11] The anterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is also important surgically as it is used as the “cable graft” to repair peripheral nerves such as the digital nerve.[12]

Knowledge of the anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve plays a significant role in several vascular surgeries involving the upper arm. Examples of these surgeries include arteriovenous fistula formation between the brachial artery and basilic vein as well as the brachial artery and vein, arteriovenous fistula steal syndrome surgery, thrombectomies, and embolectomies of the brachial artery.[13]

Clinical Significance

Knowledge of the anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve is vital clinically as the nerve is prone to damage during various procedures such as venipunctures, therapeutic injections for elbow pain, and cubital tunnel releases.[2][14] Accidental damage to the nerve following such procedures has been found to result in painful paresthesias, dysesthesias, and numbness.[7]

Snapping elbow refers to a condition where flexion and extension of the elbow causes a painful, popping sensation which at times can even be heard, seen, and palpated. This condition is most often the result of ulnar nerve dislocation over the medial epicondyle. There are reports of patients who described a similar painful popping sensation of the elbow and were found to have a snapping of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve.[15][16]

The medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve, along with many other upper extremity nerves, is prone to injury in athletes who perform repetitive throwing motions. Throwing motions damage these nerves by creating compression and traction, leading to various neuropathic syndromes.[17] Rare causes of damage to the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve include subcutaneous lipomas, lacerations, and neuritis caused by tuberculoid leprosy.[7]

Other Sources of Damage to the Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm

Other sources of damage to the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm include elbow arthroscopy, open fracture fixation, medial epicondylitis for which steroids are injected, incision of tumors, arthrolysis, and trauma from playing tennis, and compression neuropathy due to the presence of a lipoma.[18] In addition, prolonged vigorous shaking activity, such as shaking a rug, can result in neuropathy of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm.[18] Vascular branches can also be involved in Raynaud syndrome.[19]

Percutaneous Biopsy and Nerve Blocks to the Medial Cutaneous Nerve of the Forearm

Percutaneous biopsy of the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm has been shown to facilitate the diagnosis of pathological conditions involving this nerve.[20] Medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve blocks have been shown to be effective in surgery involving arteriovenous fistulas occurring in patients with end-stage renal disease.[21] Ultrasound-guided nerve blocks have been proven effective in surgical upper limb anesthesia, including the medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm.[22]

Media

References

Li H, Zhu W, Wu S, Wei Z, Yang S. Anatomical analysis of antebrachial cutaneous nerve distribution pattern and its clinical implications for sensory reconstruction. PloS one. 2019:14(9):e0222335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222335. Epub 2019 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 31509579]

Stylianos K, Konstantinos G, Pavlos P, Aliki F. Brachial branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve: A case report with its clinical significance and a short review of the literature. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice. 2016 Jul-Sep:7(3):443-6. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.182772. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27365965]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThomas K, Sajjad H, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Medial Brachial Cutaneous Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969651]

Polcaro L, Charlick M, Daly DT. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Brachial Plexus. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30285368]

Chang KV, Mezian K, Naňka O, Wu WT, Lou YM, Wang JC, Martinoli C, Özçakar L. Ultrasound Imaging for the Cutaneous Nerves of the Extremities and Relevant Entrapment Syndromes: From Anatomy to Clinical Implications. Journal of clinical medicine. 2018 Nov 21:7(11):. doi: 10.3390/jcm7110457. Epub 2018 Nov 21 [PubMed PMID: 30469370]

Race CM, Saldana MJ. Anatomic course of the medial cutaneous nerves of the arm. The Journal of hand surgery. 1991 Jan:16(1):48-52 [PubMed PMID: 1995693]

Jung MJ, Byun HY, Lee CH, Moon SW, Oh MK, Shin H. Medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve injury after brachial plexus block: two case reports. Annals of rehabilitation medicine. 2013 Dec:37(6):913-8. doi: 10.5535/arm.2013.37.6.913. Epub 2013 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 24466530]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim S, Dennis M, Holland J, Terrell M, Loukas M, Schober J. The anatomy of forearm free flap phalloplasty for transgender surgery. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Mar:31(2):145-151. doi: 10.1002/ca.23014. Epub 2017 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 29178477]

Masear VR, Meyer RD, Pichora DR. Surgical anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. The Journal of hand surgery. 1989 Mar:14(2 Pt 1):267-71 [PubMed PMID: 2703673]

Benedikt S, Parvizi D, Feigl G, Koch H. Anatomy of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and its significance in ulnar nerve surgery: An anatomical study. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2017 Nov:70(11):1582-1588. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2017.06.025. Epub 2017 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 28756975]

Lowe JB 3rd, Maggi SP, Mackinnon SE. The position of crossing branches of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve during cubital tunnel surgery in humans. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2004 Sep 1:114(3):692-6 [PubMed PMID: 15318047]

Nunley JA, Ugino MR, Goldner RD, Regan N, Urbaniak JR. Use of the anterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve as a graft for the repair of defects of the digital nerve. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1989 Apr:71(4):563-7 [PubMed PMID: 2703516]

Przywara S. Importance of medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve anatomical variations in upper arm surgery. Journal of neurosciences in rural practice. 2016 Jul-Sep:7(3):337-8. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.181484. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27365947]

Asheghan M, Khatibi A, Holisaz MT. Paresthesia and forearm pain after phlebotomy due to medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve injury. Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. 2011 Sep 6:6():5. doi: 10.1186/1749-7221-6-5. Epub 2011 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 21896172]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCesmebasi A, O'driscoll SW, Smith J, Skinner JA, Spinner RJ. The snapping medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Oct:28(7):872-7. doi: 10.1002/ca.22601. Epub 2015 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 26212210]

Bjerre JJ, Johannsen FE, Rathcke M, Krogsgaard MR. Snapping elbow-A guide to diagnosis and treatment. World journal of orthopedics. 2018 Apr 18:9(4):65-71. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i4.65. Epub 2018 Apr 18 [PubMed PMID: 29686971]

Hariri S, McAdams TR. Nerve injuries about the elbow. Clinics in sports medicine. 2010 Oct:29(4):655-75. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20883903]

Yildiz N, Ardic F. A rare cause of forearm pain: anterior branch of the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve injury: a case report. Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. 2008 Apr 21:3():10. doi: 10.1186/1749-7221-3-10. Epub 2008 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 18426569]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUmemoto K, Ohmichi M, Ohmichi Y, Yakura T, Hammer N, Mizuno D, Naito M, Nakano T. Vascular branches from cutaneous nerve of the forearm and hand: Application to better understanding raynaud's disease. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Jul:31(5):734-741. doi: 10.1002/ca.22993. Epub 2017 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 28960445]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu KY, Murthy NK, Howe BM, Dyck PJB, Spinner RJ. Diagnostic value of proximal cutaneous nerve biopsy in brachial and lumbosacral plexus pathologies. Acta neurochirurgica. 2023 May:165(5):1189-1194. doi: 10.1007/s00701-023-05565-y. Epub 2023 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 37009932]

Viscomi CM, Reese J, Rathmell JP. Medial and lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve blocks: an easily learned regional anesthetic for forearm arteriovenous fistula surgery. Regional anesthesia. 1996 Jan-Feb:21(1):2-5 [PubMed PMID: 8826018]

Sehmbi H, Madjdpour C, Shah UJ, Chin KJ. Ultrasound guided distal peripheral nerve block of the upper limb: A technical review. Journal of anaesthesiology, clinical pharmacology. 2015 Jul-Sep:31(3):296-307. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.161654. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26330706]