Introduction

Parotidectomy is the partial or complete removal of the parotid gland; the procedure may be indicated for various reasons, including inflammatory conditions, certain infectious processes, congenital malformations, and benign or malignant neoplasms. Regardless of the indication for surgery, parotidectomy is a meticulous procedure requiring experienced surgeons, particularly due to the relationship of the gland to the facial nerve. Therefore, identification and preservation of the facial nerve are the most crucial steps during the procedure (second only to oncologic safety in the case of known malignancy). Emphasis is placed on identification because, in the vast majority of cases, preoperative prediction of the relationship of the tumor to the facial nerve is not possible with much accuracy unless facial paralysis is present before intervention.[1][2][3][4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The parotid gland is the largest major salivary gland. This gland is bounded by the masseter muscle anteriorly, the zygomatic arch superiorly, the anteromedial aspect of the sternocleidomastoid muscle inferiorly, and the external auditory canal posteriorly. The facial nerve divides the gland virtually into superficial and deep lobes. The superficial lobe is lateral; the facial nerve and the deep lobe extend medially into the parapharyngeal space. However, this division is not anatomical since no true embryologic or fascial plane exists between the pars superficialis and pars profunda. The parotid gland is encased by a prolongation of the deep cervical fascia, which divides into a deep and superficial layer to surround the gland. The superficial fascia extends from the masseter and sternocleidomastoid to the zygomatic arch. The superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) extends superiorly from the platysma to the superficial temporal fascia. The SMAS lies superficial to the parotid fascia.[1][4]

The parotid duct (Stenson duct) exits the gland anteriorly and follows a course approximately 1 cm inferior to and parallel to the zygomatic arch. After crossing the masseter, the duct pierces the buccinator muscle and enters the oral cavity, facing the second maxillary molar. Salivary secretions of the parotid gland are more serous in contrast with the submandibular gland, which secretes a more mixed serous/mucous saliva. This explains the higher incidence of sialolithiasis within the submandibular gland.[5][6]

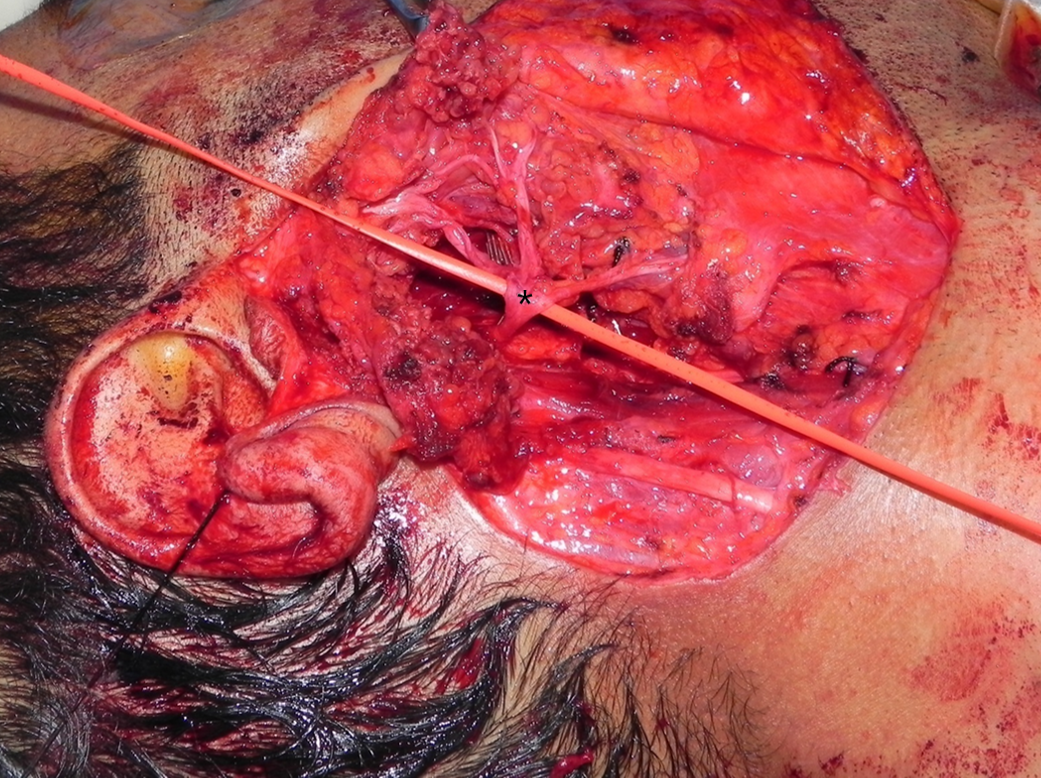

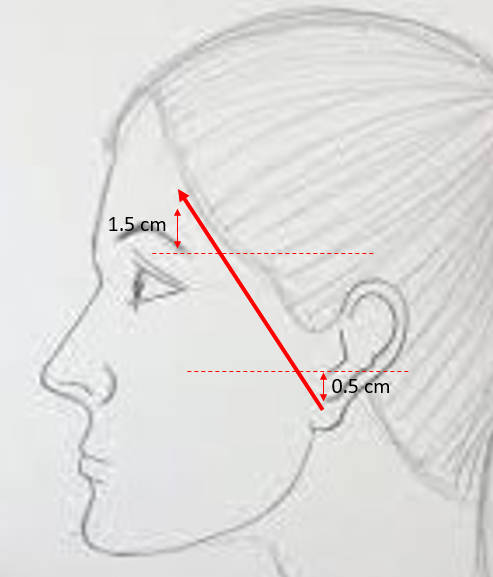

Relevant facial nerve anatomy is limited to its extemporal portion. After leaving the stylomastoid foramen, the main trunk of the facial nerve divides at the pes anserinus (see Image. Total Parotidectomy Visualized During Surgery) into 2 divisions: the temporofacial branching into frontal, zygomatic, and buccal branches, and the cervicofacial giving rise to the marginal mandibular and cervical branches. The course of the temporal branch can be predicted using surface landmarks as described by Pitanguy et al: a line starting from a point 0.5 cm below the tragus in the direction of the eyebrow, passing 1.5 cm above the lateral extremity of the eyebrow (see Image. The Course of the Temporal Branch). The middle branch of the facial nerve (zygomatic/buccal) can be identified at the Zuker point, which lies midway on a line drawn from the root of the helix and the lateral commissure of the mouth with a 6 mm accuracy (see Image. The Course of the Facial Nerve). Note the buccal branch accompanies the Stenson duct over the masseter muscle. The marginal mandibular branch is located immediately in a plane deep to the platysma in proximity to the inferior border of the mandible. Along its course, the branch runs superficial to the facial vessels (see Image. Surgical Landmarks for the Main Trunk of the Facial Nerve). The retromandibular vein travels deeply through the parotid gland to the facial nerve (see Image. Superficial Parotidectomy for A Benign Salivary Gland Tumor). Since the facial nerve cannot be detected on a computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the retromandibular vein is a useful radiologic landmark for the superficial and deep lobes of the gland. With the advent of 3 Tesla MRI, imaging of the intra-parotid facial nerve is occasionally possible; however, concerns exist regarding accuracy and reproducibility, particularly in parotid neoplasms.[4][7][8][9][10]

Another structure worth mentioning is the greater auricular nerve that travels parallel to the external jugular vein and splits into an anterior and posterior branch at the level of the tail of the parotid gland. Injury to this nerve leads to loss of sensation in the skin at the angle of the mandible, the side of the upper neck, and the inferior half of the external ear. Of note, preservation of the anterior branch is often impossible as the structure frequently overlies the tail of the parotid and physically hampers exposure of the tail of the gland while raising the skin flap. The greater auricular nerve can also be used as a nerve graft in the event of a facial nerve injury.[11]

The parotid gland contains lymph nodes in the superficial and deep lobes with a 90% to 10% distribution, respectively. The superficial group drains the pinna, scalp, eyelids, and lacrimal glands; the deep group drains the gland, middle ear, nasopharynx, and soft palate; and the external auditory canal drains into both groups. This is important in the setting of sentinel lymph node biopsy, which may necessitate superficial or total parotidectomy for melanoma or other epithelial tumors of these regions.[12]

Indications

By far, the most common indication for parotidectomy is the removal of a neoplasm. In 75% to 80% of cases, these neoplasms are benign and of primary parotid origin. Pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin tumors represent the majority of tumors, with pleomorphic adenoma representing the most common benign parotid tumor. Of malignant tumors, mucoepidermoid and adenoid cystic carcinoma are the 2 most common primary parotid tumors. Metastasis from a cutaneous primary represents the most common parotid malignancy, notably in Australia.[13] Chronic parotitis and recurrent sialadenitis are treated with a parotidectomy when medical treatment and sialoendoscopy fail or are unavailable. Other indications include caseating granulomas, toxoplasmosis, branchial cleft cysts, symptomatic lymphoepithelial cysts, or tuberculosis.[14][15][16][17][18]

Every patient should be evaluated properly before surgery. History and physical exams are essential for optimal decision-making. Most patients are asymptomatic and present with an enlarging mass that was incidentally noted. Pain, if present, is not predictive of malignant histology. A fixed mass could be malignant, inflammatory, or located in the deep lobe. However, benign masses can have limited mobility owing to the gland parenchyma's dense structure, so they have more limited predictive utility. Examination of the oral cavity is useful to rule out the involvement of the parapharyngeal space. Facial nerve function is examined and ideally is documented with photographs. Worrisome signs include facial paralysis, trismus, formication, and numbness.[1] The neck is palpated systematically; a parotid tail lesion might be mistaken for a jugulodigastric node.

The British guidelines recommend ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for every patient.[19] These guidelines have an accuracy of 96% in distinguishing benign from malignant neoplasm.[20] The findings of FNAC differ from clinical findings. For example, a Warthin tumor on FNAC in a very young patient should not necessarily reassure the surgeon into advising observation; this could represent a low-grade mucoepidermoid carcinoma since typically benign tumors present at more advanced ages. Each patient's clinical picture must be used to make decisions rather than any single test.[21] Core biopsy is helpful when FNAC is not sufficient for diagnosis. This procedure has a 96% sensitivity and 100% specificity for diagnosing malignancy.[22] The frozen section's role is unclear; however, this may be able to differentiate malignancy from benign pathology with 99% specificity reported in some studies. Similarly, surgical margins are determined, except for the tissue directly abutting the facial nerve, a variable subject to local pathologists' expertise. For this reason, some authors prefer to forgo frozen sections and await permanent histology, counseling patients that a second operation may be required. Computed tomography scans with contrast and MRIs are useful for delineating the extent of the lesion. Most importantly, deep lobe lesions offer subtle findings on physical exams, making imaging potentially more helpful for diagnosis and preoperative planning. Static MRI parameters can help differentiate a benign from a malignant lesion with a diagnostic accuracy of 95% when accounting for well-defined margins. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, with a resultant time signal intensity curve, has a 96.5% diagnostic accuracy for differentiating benign and malignant lesions. This modality can also differentiate a malignant lesion from a Warthin tumor and pleomorphic adenoma by studying the T-peak time, and this is especially useful since pleomorphic adenoma shows a cumulative malignant transformation risk of 1% per year, in contrast to a Warthin tumor that shows only a 0.3% overall risk of malignant transformation. Studying the apparent diffusion coefficient is also helpful. When the cut-off value is 1.3 × 10-3 mm2/s and excluding lymphomas, the diagnostic accuracy for differentiating Warthin from a malignant tumor is 94.28%. This value is at 97.06% for pleomorphic adenoma.[23]

MRI sialography is a useful technique replacing conventional sialography in most centers; the modality can also help evaluate Sjogren disease by showing sialectasis clearly.[24] The availability of these more specialized MRI protocols may limit their utility in some centers. Neck dissection is always performed in the event of clinically or radiographically evident cervical metastasis. For a node-negative neck, recommendations are less robust, with most authors suggesting dissection of levels I to III for high-grade lesions, T3/T4 tumors, and advanced ages since these are risk factors for locoregional recurrence. Adjuvant radiotherapy is indicated for T3/T4 tumors, close or positive margins, and perineural/perivascular invasion. Nearly all adenoid cystic carcinoma can benefit from adjuvant radiotherapy. Therapeutic radiation is acceptable when surgery is not feasible. Conventional chemotherapy has demonstrated consistently poor outcomes as a primary treatment modality in salivary gland tumors, though use in ongoing trials is prevalent within a palliative setting.[20]

The TNM staging system is frequently used for major salivary gland tumors (T describes the tumor's size and any cancer spread into nearby tissue; N describes the spread of cancer to nearby lymph nodes; and M describes metastasis. Taro et al analyzed data from 4520 patients in the United States National Cancer Database to create an adapted lymph node staging system for salivary gland tumors. Mortality increased rapidly for every lymph node below 4 and at a slower pattern above 4. The staging system can also be criticized for encompassing all types of salivary gland tumors, while obviously, each histologic subtype behaves differently. The standard of care staging system remains the American Joint Committee on Cancer, AJCC, 8th edition as of the date of this article.[25]

Types of parotid surgery include:

- Extracapsular dissection: The facial nerve is not identified; the tumor is resected with the help of a facial nerve monitor (discussion beyond the scope of this chapter), which is used for benign lesions that are not pleomorphic adenoma.

- Partial/superficial parotidectomy: The tumor is resected with a cuff of parotid tissue while identifying and preserving the facial nerve, used for benign lesions and lymph node metastasis into the superficial lobe.

- Total parotidectomy: The entire gland is removed with identification and preservation of the facial nerve. The approach is used for aggressive malignant tumors, deep lobe tumors, sentinel lymph node excision when located in the deep lobe, vascular malformations, or large tumors where the distinction between superficial and deep lobes is unclear.

- Radical parotidectomy: The entire gland, including the facial nerve, is removed. This procedure is mostly used when preoperative facial paralysis is well established or a malignant tumor circumferentially involves the nerve. Simultaneous nerve grafting or other facial reanimation procedures are employed in this situation.

The patient needs to be counseled before surgery about the risk of temporary or permanent facial paralysis, the need for a suction drain, compressive dressing, and the possibility of an aesthetic contour deformity at the site of surgery.[26]

Contraindications

No contraindications for parotidectomy exist as long as the patient is medically fit for general anesthesia. While reports of this procedure being performed under local anesthesia are available, this is unusual and not routinely recommended. In some instances, intubation might be challenging, for example, a tumor extending to the deep lobe/the parapharyngeal space or an extensive lesion invading the temporomandibular joint leading to trismus. In such situations, awake nasal fiberoptic intubation or a tracheostomy is necessary to secure the airway. In certain conditions, parotidectomy might not be the optimal management technique. While most neoplasms are managed surgically, not all parotid masses are truly neoplastic. A patient with human immunodeficiency virus and parotid swelling is likelier to have intraparotid lymphoepithelial cysts and should have a detailed imaging and/or cytologic workup. Surgery is a last resort, given the bilateral and progressive nature of the disease and the higher risk of facial nerve injury. More appropriate options include observation, repeat aspiration, antiretroviral medication, sclerosing therapy, or radiation therapy.[27]

Equipment

Parotid surgery can be performed with the basic instruments used in head and neck operations. Bipolar is used for hemostasis. Nerve monitoring can be done by asking a dedicated assistant to watch the face for twitches. However, continuous electromyography nerve monitoring is the standard of care in many centers. This can be utilized via an intraoperative electrophysiological facial nerve monitor and/or a handheld nerve locator.

Evidence in the literature suggests the following concerning electromyographic facial nerve monitoring:

- Decreases the rate of immediate facial weakness in primary surgeries

- Helps localize the facial nerve

- Mandatory in extracapsular resection where, by definition, the facial nerve is not identified

- Offers prognostic value regarding postoperative facial nerve function [20]

Technique or Treatment

The procedure is performed under general anesthesia with the endotracheal tube fixed to the contralateral side. The anesthesia team should be advised to avoid muscle relaxants because facial nerve function needs to be monitored. The neck is slightly extended, and the head is turned away from the operated side. Half of the face is scrubbed with an antiseptic solution with care not to damage the eye. Drapes are placed with care to expose the hemiface and neck. If a nerve integrity monitor (NIM) is used, 4 electrodes are placed in the area of the facial nerve's temporal, zygomatic, buccal, and marginal mandibular branches. Most surgeons prefer the modified Blair incision, starting in a preauricular skin crease around the lobule posteriorly and extending inferiorly into a cervical skin crease. Some skin should be left around the lobule to avoid deformity of pixie-ear (or satyr). An alternative is the modified facelift incision, which starts similar to a modified Blair incision; however, after turning around the lobule, the incision extends posteriorly and superiorly into the retro auricular crease to continue within the occipital hairline.[28][29]

After incising the dermis and platysma, an anterior skin flap is raised in a plane between the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) and the superficial capsule of the parotid. A thick flap is advised to minimize the risk of Frey syndrome and skin necrosis. Some surgeons advocate dissection in a plan just deep the superficial parotid fascia to further decrease the risk of Frey syndrome. Another option is to raise a supra-SMAS flap, not injuring the subdermal plexus, and then raise a second SMAS flap in a facelift style. This SMAS flap can be re-attached to minimize cosmetic deformity and Frey syndrome. Care is taken anteriorly not to damage branches of the facial nerve that become superficial at this level.

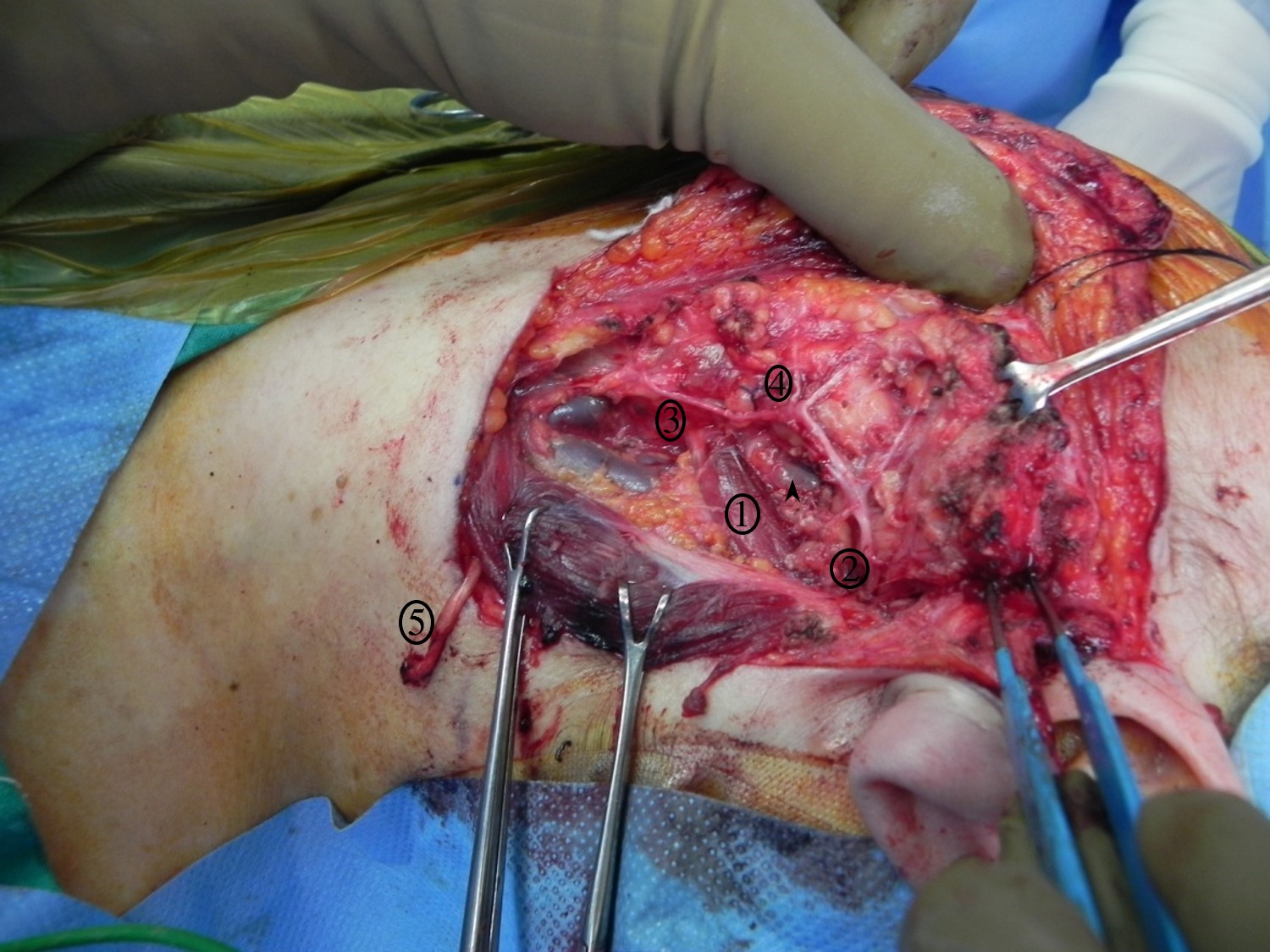

Classically, the greater auricular nerve is sacrificed during the procedure; however, preserving the posterior branch is possible. This is done by careful dissection along the nerve after its identification while raising the cervical subplatysmal flap; at the level of the bifurcation, the anterior branch is divided. If the entire nerve is sacrificed, this should be done as distal as possible to preserve a lengthy segment if a cable graft is considered for facial nerve reconstruction (see Image. Superficial Parotidectomy for A Benign Salivary Gland Tumor). The assistant plays a crucial role during the procedure by monitoring the face for muscle contractions if an NIM is used, remembering the NIM and bipolar are assisting (the surgeon should rely on direct observation before solely relying on electronic devices). Skin flaps are retracted and fixed with silk sutures or other retractive methods. Next, the tail of the parotid is dissected from the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle. The external jugular vein might be divided and ligated. However, the vein can also frequently be preserved, as this might decrease bleeding during the procedure or provide a vessel for anastomosis for reconstructive flaps.[1]

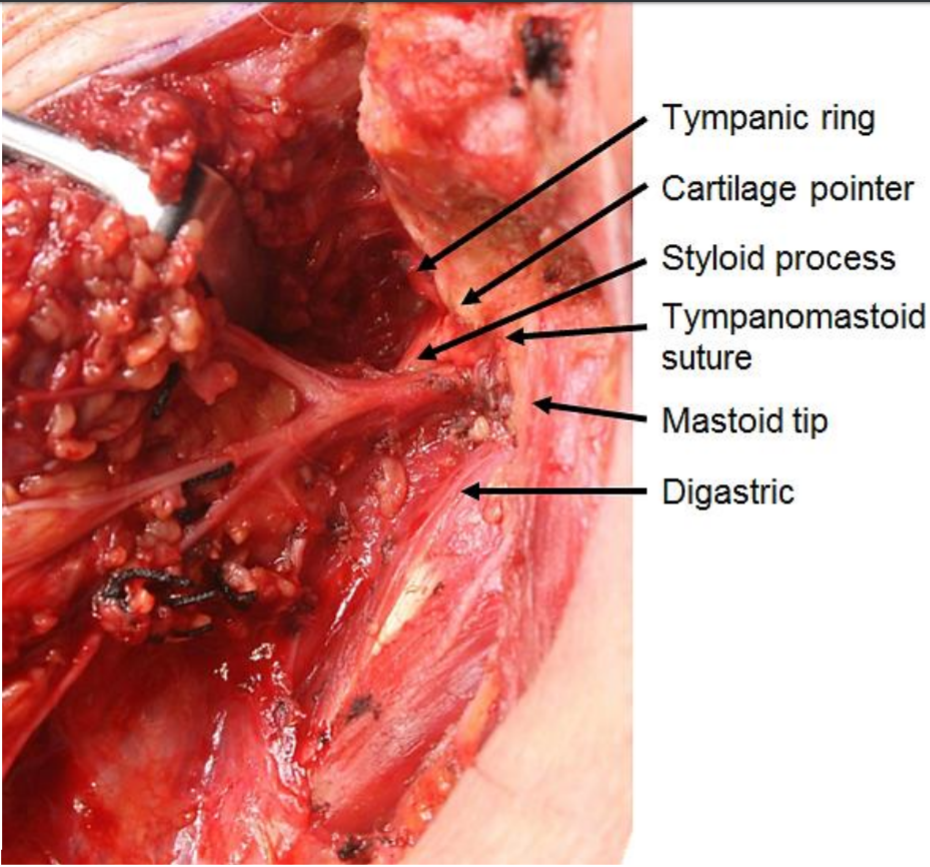

The tail of the parotid is retracted superiorly, and the digastric muscle is identified. The muscle serves as a landmark for the facial nerve. The posterior belly of the digastric inserts into the mastoid tip, so tissue superficial to this structure can be divided with relative impunity once the distal marginal mandibular branch has been located. Dissection cephalad to the digastric muscle might injure the facial nerve as it exits the stylomastoid foramen between the mastoid and styloid processes. The attachments of the gland to the cartilage of the external auditory canal and the SCM muscle are divided to allow rotation and mobilization of the gland, a crucial step for identifying the facial nerve. A useful trick in adults is to palpate the mastoid tip, remove the overlying non-salivary gland tissue, and attach the tissue to the parotid. This can be done safely without concerns of facial nerve injury. The maneuver in children is ill-advised since the mastoid tip is poorly developed, placing the facial nerve at risk. The cartilage of the external auditory canal is dissected up to the level of the tragal pointer, another landmark for identification of the main trunk of the facial nerve, which is located roughly 1 cm inferior and anterior to it. The pointer is a cartilaginous structure that can be fractured or dislocated during the dissection; this factor must be considered when used as a landmark for the facial nerve. At this point, the surgeon can palpate the tympanomastoid suture, the most reliable landmark for identifying the main trunk of the facial nerve. Emphasis is on palpation since visualizing the suture is difficult. The tympanomastoid suture is considered the most consistent and reliable landmark for the main trunk of the facial nerve, which emerges a few millimeters deep to its lateral edge.[30][31]

At this point, the surgeon should have dissected the attachments of the gland from the external auditory canal and the SCM muscle, identified the digastric muscle, the tragal pointer, the tympanomastoid suture, and be ready to begin the delicate and tedious task of identifying of the facial nerve and the dissection along its branches (see Image. Surgical Landmarks for the Main Trunk of the Facial Nerve). With a fine hemostat or McCabe dissector, the main trunk of the facial nerve is located and followed distally. Dissecting directly atop the nerve is necessary for visualization. Divide the parotid tissue overlying the area of the facial nerve that has been dissected, never beyond that area. This can be done with fine scissors or a #12 blade while the hemostat splays the glandular tissue. Hemostasis is ensured with bipolar diathermy and fine ties (when tightening the knots, applying pressure on the facial nerve and branches is contraindicated with the tightening finger). Ligasure is believed to reduce surgical time without increasing the risk of complications.[32] When the pes anserinus is reached, visualizing the entire portion of the proximal facial nerve is advised to ensure no early branching occurs. Continue dissection along the branches of the facial nerve. Unless a complete superficial parotidectomy is planned, dissect only along branches proximal to the tumor. The retromandibular vein is often encountered deep in the facial nerve during the process. When removing the superior part of the gland, the superficial temporal artery may need to be ligated; if so, this is performed just anterior to the auricle. When dissection continues anteriorly, the parotid duct is reached and divided if necessary. Remember that the buccal branch of the facial nerve is adjacent to the duct. Eventually, the tumor is removed with a cuff of parotid tissue or the entire superficial lobe.

When removing the deep lobe of the parotid, the surgeon can remove the superficial lobe completely or free the lobe while preserving anterior attachment, reflecting the attachment away, and replacing it at the end of the procedure. Branches of the facial nerve are released from the tissue of the deep lobe with blunt and sharp dissection (see Image. Total Parotidectomy Visualized During Surgery). The tumor can be removed through splayed facial nerve branches or inferiorly retracting the mass. Suppose this proves to be difficult or inadequate. In that case, the transcervical approach with the division of the stylomandibular ligament provides excellent exposure of the parapharyngeal space, including the parotid's deep lobe. Orabi et al managed to remove 9 out of 9 benign tumors of the parapharyngeal space by dividing the stylomandibular ligament and retracting the mandible anteriorly. Vascular structures that need to be ligated and divided when necessary while maneuvering within the parapharyngeal space can include the external carotid, deep transverse facial, superficial temporal arteries, and the retromandibular and superficial temporal veins.[33] Of note, when performing total parotidectomy for chronic parotitis, the Stenson duct needs to be followed up to the oral mucosa to avoid retention of any stones within a distal stump, which might lead to subsequent infection.

Benign tumors can almost always be dissected free from the facial nerve without problems. Facial nerve preservation is always the rule, even with pleomorphic adenoma, where a certain margin is required to avoid recurrence. This adenoma has only a small risk of recurrence when resected via true superficial parotidectomy. However, some malignant tumors might invade the nerve and raise the question of the invasion branch's sacrifice. If preoperative facial paralysis is present, every effort should be made to achieve complete tumor resection, even if it requires excising a portion of the facial nerve. When no preoperative paralysis is documented, shaving the tumor off the nerve (R1 resection) is acceptable, though many authors advocate resection of the affected branches and primary cable grafting. Isolated midfacial branches might not need to be repaired because the resulting deformity is often unnoticed.[15][34]

In the event of tumor spillage, when operating on a pleomorphic adenoma, the substance should be suctioned, and the site of capsule rupture should be closed. Some experts recommend against site irrigation since this might spread tumor cells all over the field. Some believe this spillage increases the risk of recurrence; however, no data supports this claim. The role of adjuvant radiotherapy in this setting is unclear.[20] Before closure, the integrity of the facial nerve is checked, and function can be assessed with a nerve stimulator. Judicious nerve stimulation is advised since excessive electric stimulation might lead to neuropraxia. Sometimes mechanical trauma induces neuropraxia, and twitches are not observed. After meticulous hemostasis, a suction drain is inserted, and the wound is closed in 2 layers.

In the recovery room, facial nerve function should be assessed immediately. Some facial weakness is to be expected, particularly in total parotidectomy. This typically resolves with time so long as all branches are definitively identified and preserved, though full recovery can take many months. The drain is left in place until the output is less than 15 to 50 cc in 24 hours. The duration of compressive dressing is variable, and some experts remove the dressing when the drain can be removed; others insist on the importance of a compressive dressing, especially after drain removal.

A recent meta-analysis revealed outpatient parotidectomy may be as safe as inpatient parotidectomy in appropriately selected patients. However, many studies lacked explicit selection criteria. Most of the cited exclusion criteria from same-day surgery included comorbidities, lack of social support, not living within proximity to the hospital, or malignant diagnosis.[35]

Coniglio, et al reported their experience with outpatient drainless parotidectomy. They established the viability of this approach in a properly selected patient:

- Extracapsular parotidectomy with identification of selected branches of the facial nerve when needed without identification of the main trunk

- Minimal SMAS disruption and reconstruction at the end of the procedure primarily

- When SMAS reconstruction is not possible, grafting material was used to fill the dead space

- Jaw-bra compression dressing for 48 hours and then overnight as tolerated [36]

Complications

The following are common complications after parotidectomy:

- Hematoma: There is a 0.9% prevalence of hematoma in cases of parotidectomy. Meticulous hemostasis is the key to prevention and surgical reintervention to control bleeders.

- Facial paralysis: When anatomically identified and branches are known to be intact, the most probable cause of the paralysis is stretching. This is also supported by the significantly more common incidence of paresis/paralysis in total parotidectomy when compared to superficial parotidectomy. The incidence of transient paralysis is somewhere between 16.6% to 34%, and 90% will recover within 1 month; however, paralysis could last as long as 18 months. The ability to close the eye without any corneal exposure needs to be assessed, and preventive measures are indicated to prevent exposure to keratitis. Ophthalmic drops and ointments, ophthalmologist consultation, gold weights, and botulinum toxin are all potential treatment options in this interim.

- Seroma: This is managed by needle aspiration and compression dressing

- Surgical site infection: Prophylactic antibiotics are controversial. Extensive procedures with neck dissection and free flap reconstruction are at higher risk of infection and benefit from perioperative antibiotics. In more standard parotidectomy, intraoperative antibiotics are sufficient in most patients.

- Frey syndrome: This syndrome is more accurately referred to as gustatory sweating. Patients report facial swelling and sweating at the site of the parotidectomy in occurrence with meals. The etiology is believed to be aberrant innervation of the sweat glands, with branches emerging from the auriculotemporal nerve after their division during surgery. This provides parasympathetic innervation to the normally sympathetic-innervated sweat glands. Diagnosis is usually based on patient history; however, if the iodine-starch test (Minor test) is inconclusive, the iodine starch placed on the affected area turns blue, signaling sweat secretion. The incidence historically has been reported as high as 50% to 100%, though, with modern techniques and the use of SMAS flaps and thicker skin flaps at the time of initial elevation, this is greatly reduced and is now quite rare. Should this syndrome develop, surgical treatment options are disappointing, with the best results obtained using SMAS and superficial temporal artery flaps as a barrier between the surgical site and the skin. The gold standard treatment now is botulinum toxin injection. Relief of symptoms is obtained for 6 to 36 months. This treatment works at the pre-synaptic level of the neuromuscular and neuroglandular junction by blocking the release of acetylcholine.

- First-bite syndrome: Painful spasm in the parotid region occurs at the first bite during mastication and decreases afterward. This pain accompanies each meal usually. The syndrome is a unique complication of surgeries targeting the deep lobe of the parotid gland, the parapharyngeal space, and the infratemporal fossa. The presumed etiology is the loss of sympathetic innervation of the parotid gland, leading to relative parasympathetic overstimulation, resulting in the contraction of parotid myoepithelial cells. Leaving the superficial lobe in place increases the risk of first-bite syndrome. Treatment is often challenging and begins with carbamazepine, which must be titrated. Most patients report improvement with time but never complete recovery. This is exceedingly rare and only encountered in extensive parotidectomy and extended neck dissections that violate the deep fascia of the floor of the neck, traumatizing the superior cervical ganglion. Loss of sensation around the ear, especially the lobule, occurs frequently. Significant but incomplete improvement is expected within 1 year. Preservation of the posterior branch of the great auricular nerve will hasten recovery. Amputation neuroma might occur when the nerve is transected; treatment is simply excision. Surgical site depression occurs proportionally to the amount of tissue resected. Reconstruction with an SCM flap is helpful, but the drawback of creating a defect in the neck should be considered. An autologous fat graft can also be used.

- Trismus: Inflammation of the master muscle is transient and mild.

- Sialocele: Salivary fistula is the result of communicating a salivary duct or the gland with the skin. Saliva is excreted through the wound. The incidence of this complication is between 4% and 14%. Treatment is by applying frequent drainage and compressive dressing. Sometimes, decreasing oral intake is necessary; completion of parotidectomy has been suggested. Botulinum toxin injection offers an excellent therapeutic outcome by blocking the salivary flow.[37][38][39][40][41][42]

Clinical Significance

Medical treatment plays a minor role in the treatment of most parotid diseases. Therefore, surgical intervention remains the cornerstone of treatment. Parotidectomy is an intricate procedure with functional, aesthetic, and potentially oncologic considerations. Knowledge of pertinent anatomy, preoperative optimization, techniques for facial nerve identification, and complications will allow the surgeon to safely and effectively care for patients requiring parotidectomy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Parotid surgery is an emotionally intense experience for the patient and the family, with most fearing postoperative disfigurement. Fortunately, the results are frequently excellent for experienced surgeons. The clinician must explain clearly to the patient what to expect, tailoring such discussions to each patient. A small benign lesion may less likely result in permanent facial paralysis but is most dependent upon its location within the gland itself. An extensive malignant tumor poses a significant risk for facial nerve injury. An interdisciplinary approach is crucial to success.

When significant resection is expected, a free flap surgeon is consulted to discuss the pros and cons of vascularized tissue reconstruction versus local flap reconstruction. Nurses familiar with head and neck surgery are the keystone to an optimal postoperative outcome; they can recognize a hematoma that needs urgent drainage, a seroma, or a salivary fistula. The role of the radiologist and the pathologist cannot be overemphasized. Preoperative delineation of the tumor by an experienced radiologist can minimize surprises during surgery and help tremendously when counseling the patient since the surgeon has a clear idea of what type of parotidectomy is indicated. A pathologist familiar with salivary glands is essential for accurately interpreting fine-needle aspiration cytology. This facilitates appropriate patient counseling and might lead to a wait-and-see approach. When the diagnosis of malignancy is confirmed or in the event of spillage of pleomorphic adenoma during surgery, a radiation oncologist is consulted to discuss the need for adjuvant radiotherapy.[10][19][20][43]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superficial Parotidectomy for A Benign Salivary Gland Tumor. Superficial parotidectomy for a benign salivary gland tumor, with identified structures: 1) digastric muscle, 2) main trunk of the facial nerve, 3) cervical branch of the facial nerve, 4) marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve, 5) great auricular nerve divided distally.

Contributed by R Moukarbel, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wang SJ, Eisele DW. Parotidectomy--Anatomical considerations. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2012 Jan:25(1):12-8. doi: 10.1002/ca.21209. Epub 2011 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 21671284]

Mutlu V, Kaya Z. Which Surgical Method is Superior for the Treatment of Parotid Tumor? Is it Classical? Is it New? The Eurasian journal of medicine. 2019 Oct:51(3):273-276. doi: 10.5152/eurasianjmed.2019.19108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31692615]

Jin H, Kim BY, Kim H, Lee E, Park W, Choi S, Chung MK, Son YI, Baek CH, Jeong HS. Incidence of postoperative facial weakness in parotid tumor surgery: a tumor subsite analysis of 794 parotidectomies. BMC surgery. 2019 Dec 26:19(1):199. doi: 10.1186/s12893-019-0666-6. Epub 2019 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 31878919]

Laing MR, McKerrow WS. Intraparotid anatomy of the facial nerve and retromandibular vein. The British journal of surgery. 1988 Apr:75(4):310-2 [PubMed PMID: 3359141]

Bialek EJ, Jakubowski W, Zajkowski P, Szopinski KT, Osmolski A. US of the major salivary glands: anatomy and spatial relationships, pathologic conditions, and pitfalls. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2006 May-Jun:26(3):745-63 [PubMed PMID: 16702452]

Porcheri C, Mitsiadis TA. Physiology, Pathology and Regeneration of Salivary Glands. Cells. 2019 Aug 26:8(9):. doi: 10.3390/cells8090976. Epub 2019 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 31455013]

Pitanguy I, Ramos AS. The frontal branch of the facial nerve: the importance of its variations in face lifting. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1966 Oct:38(4):352-6 [PubMed PMID: 5926990]

Dorafshar AH, Borsuk DE, Bojovic B, Brown EN, Manktelow RT, Zuker RM, Rodriguez ED, Redett RJ. Surface anatomy of the middle division of the facial nerve: Zuker's point. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Feb:131(2):253-257. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182778753. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23357986]

Bag AK, Curé JK, Chapman PR, Pettibon KD, Gaddamanugu S. Practical imaging of the parotid gland. Current problems in diagnostic radiology. 2015 Mar-Apr:44(2):167-92 [PubMed PMID: 25432171]

Chu J, Zhou Z, Hong G, Guan J, Li S, Rao L, Meng Q, Yang Z. High-resolution MRI of the intraparotid facial nerve based on a microsurface coil and a 3D reversed fast imaging with steady-state precession DWI sequence at 3T. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2013 Aug:34(8):1643-8. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3472. Epub 2013 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 23578676]

Iwai H, Konishi M. Parotidectomy combined with identification and preservation procedures of the great auricular nerve. Acta oto-laryngologica. 2015 Sep:135(9):937-41. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1028593. Epub 2015 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 25925072]

Kochhar A, Larian B, Azizzadeh B. Facial Nerve and Parotid Gland Anatomy. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2016 Apr:49(2):273-84. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27040583]

Mooney CP, Clark JR, Shannon K, Palme CE, Ebrahimi A, Gao K, Ch'ng S, Elliott M, Gupta R, Low TH. The significance of regional metastasis location in head and neck cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck. 2021 Sep:43(9):2705-2711. doi: 10.1002/hed.26744. Epub 2021 May 21 [PubMed PMID: 34019319]

Spiro RH. Salivary neoplasms: overview of a 35-year experience with 2,807 patients. Head & neck surgery. 1986 Jan-Feb:8(3):177-84 [PubMed PMID: 3744850]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDonovan DT, Conley JJ. Capsular significance in parotid tumor surgery: reality and myths of lateral lobectomy. The Laryngoscope. 1984 Mar:94(3):324-9 [PubMed PMID: 6321863]

Gandolfi MM, Slattery W 3rd. Parotid Gland Tumors and the Facial Nerve. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2016 Apr:49(2):425-34. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.12.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27040587]

van der Lans RJL, Lohuis PJFM, van Gorp JMHH, Quak JJ. Surgical Treatment of Chronic Parotitis. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2019 Jan:23(1):83-87. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1667006. Epub 2018 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 30647789]

Gallia LJ, Johnson JT. The incidence of neoplastic versus inflammatory disease in major salivary gland masses diagnosed by surgery. The Laryngoscope. 1981 Apr:91(4):512-6 [PubMed PMID: 7218997]

Sood S, McGurk M, Vaz F. Management of Salivary Gland Tumours: United Kingdom National Multidisciplinary Guidelines. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2016 May:130(S2):S142-S149 [PubMed PMID: 27841127]

Thielker J, Grosheva M, Ihrler S, Wittig A, Guntinas-Lichius O. Contemporary Management of Benign and Malignant Parotid Tumors. Frontiers in surgery. 2018:5():39. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2018.00039. Epub 2018 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 29868604]

So T, Sahovaler A, Nichols A, Fung K, Yoo J, Weir MM, MacNeil SD. Utility of clinical features with fine needle aspiration biopsy for diagnosis of Warthin tumor. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d'oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 2019 Aug 29:48(1):41. doi: 10.1186/s40463-019-0366-3. Epub 2019 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 31464652]

Witt BL, Schmidt RL. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of salivary gland lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Mar:124(3):695-700. doi: 10.1002/lary.24339. Epub 2013 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 23929672]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceElmokadem AH, Abdel Khalek AM, Abdel Wahab RM, Tharwat N, Gaballa GM, Elata MA, Amer T. Diagnostic Accuracy of Multiparametric Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Differentiation Between Parotid Neoplasms. Canadian Association of Radiologists journal = Journal l'Association canadienne des radiologistes. 2019 Aug:70(3):264-272. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2018.10.010. Epub 2019 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 30922790]

Abu-Taleb NSM, Abdel-Wahed N, Amer ME. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Magnetic Resonance Sialography in the Diagnosis of Various Salivary Gland Disorders: An Interobserver Agreement. Journal of medical imaging and radiation sciences. 2014 Sep:45(3):299-306. doi: 10.1016/j.jmir.2014.03.092. Epub 2014 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 31051982]

Aro K, Ho AS, Luu M, Kim S, Tighiouart M, Clair JM, Yoshida EJ, Shiao SL, Leivo I, Zumsteg ZS. Development of a novel salivary gland cancer lymph node staging system. Cancer. 2018 Aug 1:124(15):3171-3180. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31535. Epub 2018 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 29742277]

Wierzbicka M, Piwowarczyk K, Nogala H, Błaszczyńska M, Kosiedrowski M, Mazurek C. Do we need a new classification of parotid gland surgery? Otolaryngologia polska = The Polish otolaryngology. 2016 Jun 30:70(3):9-14. doi: 10.5604/00306657.1202390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27386927]

Shanti RM, Aziz SR. HIV-associated salivary gland disease. Oral and maxillofacial surgery clinics of North America. 2009 Aug:21(3):339-43. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2009.04.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19608050]

Maithani T, Pandey AK, Agrahari AK. An Overview of Parotidectomy for Benign Parotid Lesions with Special Reference to Perioperative Techniques to Avoid Complications: Our Experience. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2019 Oct:71(Suppl 1):258-264. doi: 10.1007/s12070-018-1261-3. Epub 2018 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 31741970]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTerris DJ, Tuffo KM, Fee WE Jr. Modified facelift incision for parotidectomy. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1994 Jul:108(7):574-8 [PubMed PMID: 7930893]

Saha S, Pal S, Sengupta M, Chowdhury K, Saha VP, Mondal L. Identification of facial nerve during parotidectomy: a combined anatomical & surgical study. Indian journal of otolaryngology and head and neck surgery : official publication of the Association of Otolaryngologists of India. 2014 Jan:66(1):63-8. doi: 10.1007/s12070-013-0669-z. Epub 2013 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 24605304]

Bushey A, Quereshy F, Boice JG, Landers MA, Baur DA. Utilization of the tympanomastoid fissure for intraoperative identification of the facial nerve: a cadaver study. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2011 Sep:69(9):2473-6. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.11.044. Epub 2011 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 21550707]

Chen SW, Hsin LJ, Lin WN, Tsai YT, Tsai MS, Lee YC. LigaSure versus Conventional Parotidectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Apr 11:10(4):. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10040706. Epub 2022 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 35455883]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOrabi AA, Riad MA, O'Regan MB. Stylomandibular tenotomy in the transcervical removal of large benign parapharyngeal tumours. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2002 Aug:40(4):313-6 [PubMed PMID: 12175832]

Cracchiolo JR, Shaha AR. Parotidectomy for Parotid Cancer. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2016 Apr:49(2):415-24. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.007. Epub 2016 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 26895698]

Benito DA, Pasick LJ, Bestourous D, Thakkar P, Goodman JF, Joshi AS. Outpatient vs inpatient parotidectomy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Head & neck. 2021 Feb:43(2):668-678. doi: 10.1002/hed.26482. Epub 2020 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 33009691]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceConiglio AJ, Deal AM, Hackman TG. Outcomes of drainless outpatient parotidectomy. Head & neck. 2019 Jul:41(7):2154-2158. doi: 10.1002/hed.25671. Epub 2019 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 30706566]

Bovenzi CD, Ciolek P, Crippen M, Curry JM, Krein H, Heffelfinger R. Reconstructive trends and complications following parotidectomy: incidence and predictors in 11,057 cases. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d'oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 2019 Nov 19:48(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s40463-019-0387-y. Epub 2019 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 31744535]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSiddiqui AH, Shakil S, Rahim DU, Shaikh IA. Post parotidectomy facial nerve palsy: A retrospective analysis. Pakistan journal of medical sciences. 2020 Jan-Feb:36(2):126-130. doi: 10.12669/pjms.36.2.1706. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32063945]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMarchese-Ragona R, De Filippis C, Marioni G, Staffieri A. Treatment of complications of parotid gland surgery. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2005 Jun:25(3):174-8 [PubMed PMID: 16450773]

Mantelakis A, Lafford G, Lee CW, Spencer H, Deval JL, Joshi A. Frey's Syndrome: A Review of Aetiology and Treatment. Cureus. 2021 Dec:13(12):e20107. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20107. Epub 2021 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 34873562]

Gualberto GV, Sampaio FMS, Madureira NAB. Use of botulinum toxin type A in Frey's syndrome. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2017 Nov-Dec:92(6):891-892. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175702. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29364460]

Linkov G, Morris LG, Shah JP, Kraus DH. First bite syndrome: incidence, risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. The Laryngoscope. 2012 Aug:122(8):1773-8. doi: 10.1002/lary.23372. Epub 2012 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 22573579]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCai YC, Shui CY, Li C, Sun RH, Zhou YQ, Liu W, Wang X, Zeng D, Jiang J, Zhu G, Wang W, Jiang Z, Tang Z. Primary repair and reconstruction of tumor defects in parotid masseter region: a report of 58 cases. Gland surgery. 2019 Aug:8(4):354-361. doi: 10.21037/gs.2019.08.01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31538059]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence