Introduction

In August 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) presented data at the National STD Prevention Conference that showed sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to rise at alarming rates. There were nearly 2.3 million cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis diagnosed in the USA in 2017, surpassing the previous record set in 2016 by more than 200000 cases, and marking the fourth consecutive year of steep increases in such diagnoses. Chlamydia remained the most commonly reported condition at the CDC. With the rise in transmission of STIs, rare diseases once considered eradicated have resurfaced. Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) is one such example.

Lymphogranuloma venereum is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by the L1, L2, and L3 serovars of the bacteria Chlamydia trachomatis. First described in 1833 by Wallace, the infection was initially thought to be climatic in origin and identified as “tropical bubo.” It was not until 1912 when Rost concluded that the disease was venereal in origin.[1] The condition has variable presentations depending on the site of bacterial inoculation. Classically, the infection characteristically presented with the development of self-limited genital ulceration and painful inguinal adenopathy or “buboes.” If left untreated, the disease process was progressive and destructive with systemic spread leading to a number of extra-genital manifestations. With the advent of antibiotic therapy, LGV had largely disappeared from Western society.[2] Since 2003, outbreaks of LGV proctocolitis have emerged in Western Europe and North America and disproportionately affect men who have sex with men (MSM).[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The risk of developing LGV is related to lifestyle and sexual practices. Acute infection requires direct inoculation of the Chlamydia bacteria in to host tissue. In the case of LGV proctocolitis, infection transmission is often via anal receptive intercourse. As with other sexually transmitted infections, promiscuity, and intercourse with multiple partners place a patient at increased risk for contracting the disease. As LGV proctocolitis has disproportionately affected homosexual men, studies have attempted to identify risk factors or behavioral patterns within this population that place an individual at increased risk for developing LGV. Using questionnaires to identify differences between asymptomatic and symptomatic homosexual men, those with LGV were more likely to have had unprotected receptive or insertive anal intercourse including fisting, have had multiple partners or “one-off” sexual encounters, had concurrent recreational drug and alcohol use (GHB and methamphetamines most commonly reported), and shared sex toys.[4][5][6]

Epidemiology

Before 2003, LGV was uncommon in the Western world. LGV was primarily endemic to tropical climates such as East/West Africa, India, Southeast Asia and the Caribbean with low prevalence in the industrialized world.[7] As such, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, with CDC input, voted to cease mandated reporting of the disease in 1995.[8] In 2003, an outbreak of LGV proctitis amongst HIV-positive MSM in Rotterdam, the Netherlands occurred which prompted a concerted effort to warn the international medical community. Shortly after the initial outbreak, published case reports demonstrated the presence of LGV proctitis in multiple large European cities. Countries in Western Europe and North America began to implement surveillance protocols amongst high-risk patients. Despite these efforts, a decade later, LGV was not mandated as a reportable infection in several European countries. Even today, only twenty-four states in the US mandate the reporting of LGV cases to the CDC, limiting data to determine disease prevalence. At the time of this review, it is still not universally mandated to report cases of LGV. Thus true epidemiologic figures remain elusive. Moreover, as noted in the 2016 ECDC's annual epidemiological report, present surveillance strategies focus primarily on high-risk populations (MSM, patients with HIV/AIDS or other STIs), it difficult to generate data applicable to the general population.

Though the determination of LGV incidence and prevalence has been challenging, data reflects a disease on the rise that disproportionately affects MSM. In 2004, as a result of the European outbreak, enhanced surveillance strategies were put in place in multiple European countries (Netherlands, UK, Germany, France, Sweden). The European Surveillance of Sexually Transmitted Infections (ESSTI) network was formed and enabled the sharing of data, along with the creation of alerts through the ESSTI_ALERT system. Using this data identified 1693 cases of LGV across eight European countries from 2004 to 2008. In all reporting countries, the incidence was trending upward. This data included countries without any LGV cases in the early stages of the outbreak, such as Denmark, Portugal, and Spain.[9] The number of cases reported was particularly significant, considering the incidence in the Netherlands had been roughly five cases annually before 2003.[10] Ongoing collection of data published by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) has continued to show a rise in the incidence of LGV. In 2014, ECDC data compiled from 21 reporting European countries revealed 1416 reported cases that year alone, a 32% increase from 2013. The vast majority of cases reported in the ECDC data (87%) were noted to be from France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, and almost all cases reported were among MSM. A population-based incidence study performed in Barcelona from January 2007 to December 2011 discovered an increase in incidence amongst MSM of 1,032% during the study period.[11] In the United States, specific data regarding LGV has not been available from the CDC. It is worth noting that reported cases of Chlamydia infection in the US have continued to rise annually per the CDC’s surveillance data.

Patients with HIV have been disproportionately affected by LGV infections. In the ECDC data, of patients with a known HIV status, 87% of confirmed LGV cases occurred in HIV-positive patients. In a meta-analysis performed by Dougan et al., it was concluded that from 1996 to 2006, HIV-positive MSM accounted for 75% of LGV cases on average in Western Europe alone.[12] A prospective, multicenter study in Germany recruited a sample of MSM to evaluate the prevalence of multiple STIs in Germany over one year from December 2009 to December 2010. Their data revealed that 58% of LGV positive patients were also HIV-positive.[10] In a meta-analysis by Ronn and Ward, the authors noted that thirteen descriptive studies had shown at least two-thirds of MSM with LGV were co-infected with HIV. In the same analysis, pooled data from 17 studies from 2000-2009 showed HIV-positive MSM were greater than eight times as likely to have HIV (OR 8.19, 95% CI 4.68-14.33) than those who had non-LGV Chlamydia infections. This data demonstrated an association that was stronger than other STIs that had reemerged during the same timeframe.[2] Proposals are that improved survival in the post-HAART era and serosorting (the practice of using HIV status as a decision making strategy when participating in sexual activity) were likely factors contributing to this association.[12]

Other prevalence estimates and case-control studies have shown that HIV-infected MSM are disproportionately affected by the emergence of LGV due to an underlying pathophysiologic mechanism. Brenchley et al. proposed that acute and chronic infection with HIV cause impairment or depletion of effector-type T cells in gastrointestinal mucosa resulting in rapid depletion of CD4+ T cells.[13] By decreasing and inhibiting mucosal immune integrity, HIV may facilitate other co-infection such as syphilis and chlamydia.[14] Moreover, the direct inoculation of infection into the rectal mucosa during receptive intercourse facilitates transmission in an already susceptible population. The susceptibility of HIV infected individuals in acquiring LGV proctitis is likely a combination of risky sexual behavior and T-cell immunodeficiency.[13][14]

Pathophysiology

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular pathogen capable of causing a broad spectrum of human disease. The clinical course of the disease depends on the site of bacterial inoculation. The L serovars of Chlamydia trachomatis have the capability of invading beyond the mucosal surface. Infectivity is mediated by binding of the organism to epithelial cells via a heparin sulfate-like ligand.[15] Following the invasion, the organism induces a lymphoproliferative reaction as it multiplies within mononuclear phagocytes in local lymph nodes.[16] Lymphangitis, abscess formation, or fibrosis may follow.

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings are often nonspecific and distinguishing LGV from other inflammatory or infectious etiologies may be challenging. Inflammation, cryptitis, and crypt abscesses are prominent histologic features of inflammation due to LGV on rectal biopsy. Crypt architectural distortion, increased inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, granuloma formation, and transmural inflammation may be evident.[17] The presence of these findings can make pathologic diagnosis indistinguishable from inflammatory bowel disease. It is reasonable to ask pathologists to rule out viral etiologies such as herpes and CMV.

History and Physical

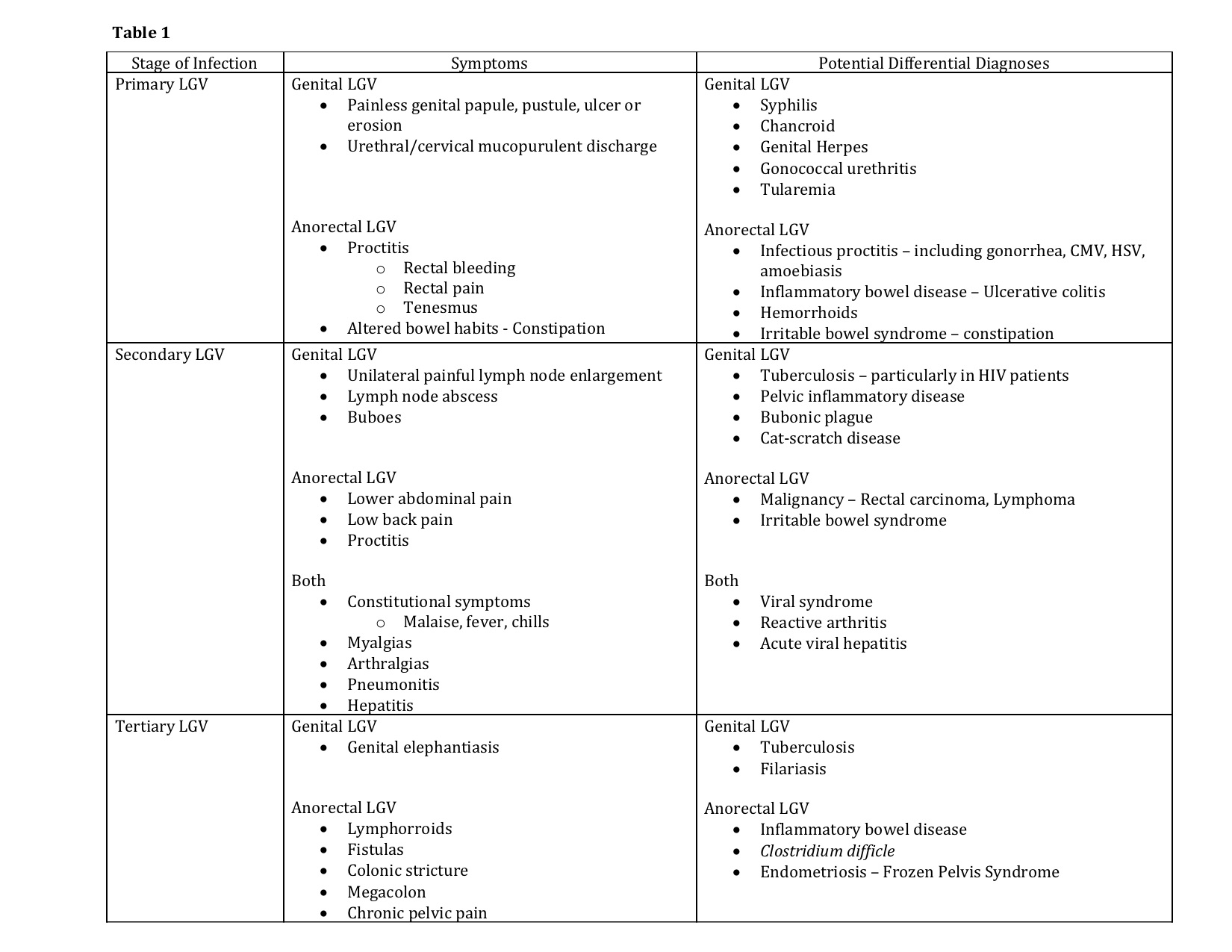

Clinically, LGV follows three stages. During the disease course, patients may have symptoms from initial infection, systemic dissemination, or the development of chronic inflammation. Symptoms vary depending on the stage at which a patient presents as well as the site of bacterial inoculation. (See Table 1)

Primary lymphogranuloma venereum

Primary LGV occurs following a 3 to 30 day incubation period, during which the first manifestations of the disease may become apparent. The resurgence of LGV has disproportionately affected men who have anal receptive intercourse. As such, the vast majority of new cases (approximately 96% in earlier estimates) present with signs and symptoms of proctitis.[18] Following the invasion of the rectal mucosa, patients may exhibit symptoms including rectal bleeding, mucoid or purulent rectal discharge, rectal pain, tenesmus, and change in bowel habits, including constipation.[16][18] Cross-sectional imaging may reveal colorectal wall thickening, and gross endoscopic findings can mimic that of acute infectious proctocolitis or an acute flare of inflammatory bowel disease. Endoscopic findings may include mucosal edema, erythema, and ulceration. If performed during this phase, endoscopic biopsies often yield nonspecific findings of inflammation such as cryptitis and crypt abscess formation. Patients may present to a clinician with presumed infectious colitis refractory to traditional first-line antibiotic therapy and/or new onset rectal bleeding. Underlying malignancy should be ruled out.

Secondary lymphogranuloma venereum

Secondary LGV occurs 2 to 6 weeks after initial exposure to the pathogen as the pathogen invades the lymphatic system. In LGV proctocolitis, this manifests as an anorectal syndrome. Direct bacterial dissemination to the deep iliac and perirectal lymph nodes may cause lower abdominal and low back pain. Lymph node involvement is often less evident in this patient population as compared to genital LGV and may only present as local lymph node prominence on cross-sectional imaging.

Systemic spread via the lymphatic system can lead to the development of constitutional symptoms such as fever, chills, generalized malaise, myalgias, arthralgias, pneumonitis, and hepatitis presenting with abnormal liver enzymes.[16] Rare complications of the disease include myocarditis, aseptic meningitis, and ocular inflammatory diseases.[19] Case reports describe reactive arthritis following confirmation of LGV proctocolitis.[20]

An inguinal syndrome may occur concurrently in some patients who have concurrently developed genital LGV. Classically, the inguinal syndrome was the first manifestation of disease in heterosexual males affected by genital LGV. The majority of cases would present with unilateral painful inguinal lymph node enlargement and abscess formation. The disease may be limited to isolated lymph nodes or groups of nodes which become involved and coalesce. A “bubo” forms as the nodes undergo necrosis, becoming purulent and fluctuant. One-third of “buboes” may rupture while the rest go on to develop into solid masses. This process may occur in the intra-abdominal, retroperitoneal, femoral, inguinal or cervical lymph node chains depending on site of inoculation.[16][19] Groove sign is pathognomonic of genital LVG but present in less than 20% of cases. This sign develops as there is preservation of the inguinal ligament despite the involvement of inguinal and femoral lymph node chains.

Tertiary lymphogranuloma venereum

Tertiary LGV demonstrates progressive, local tissue destruction and chronic inflammation caused by ongoing, untreated infection. Chronic perirectal lymphatic obstruction can produce hemorrhoid-like swellings called “lymphorroids.” Fistulas, strictures, and stenosis may form as a result of chronic lymphangitis and progressive sclerosing fibrosis, closely mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. Patients with strictures as a result of persistent LGV proctitis can develop megacolon.[21] Chronic pelvic pain may develop as a result of frozen pelvis syndrome.[22][23]

Evaluation

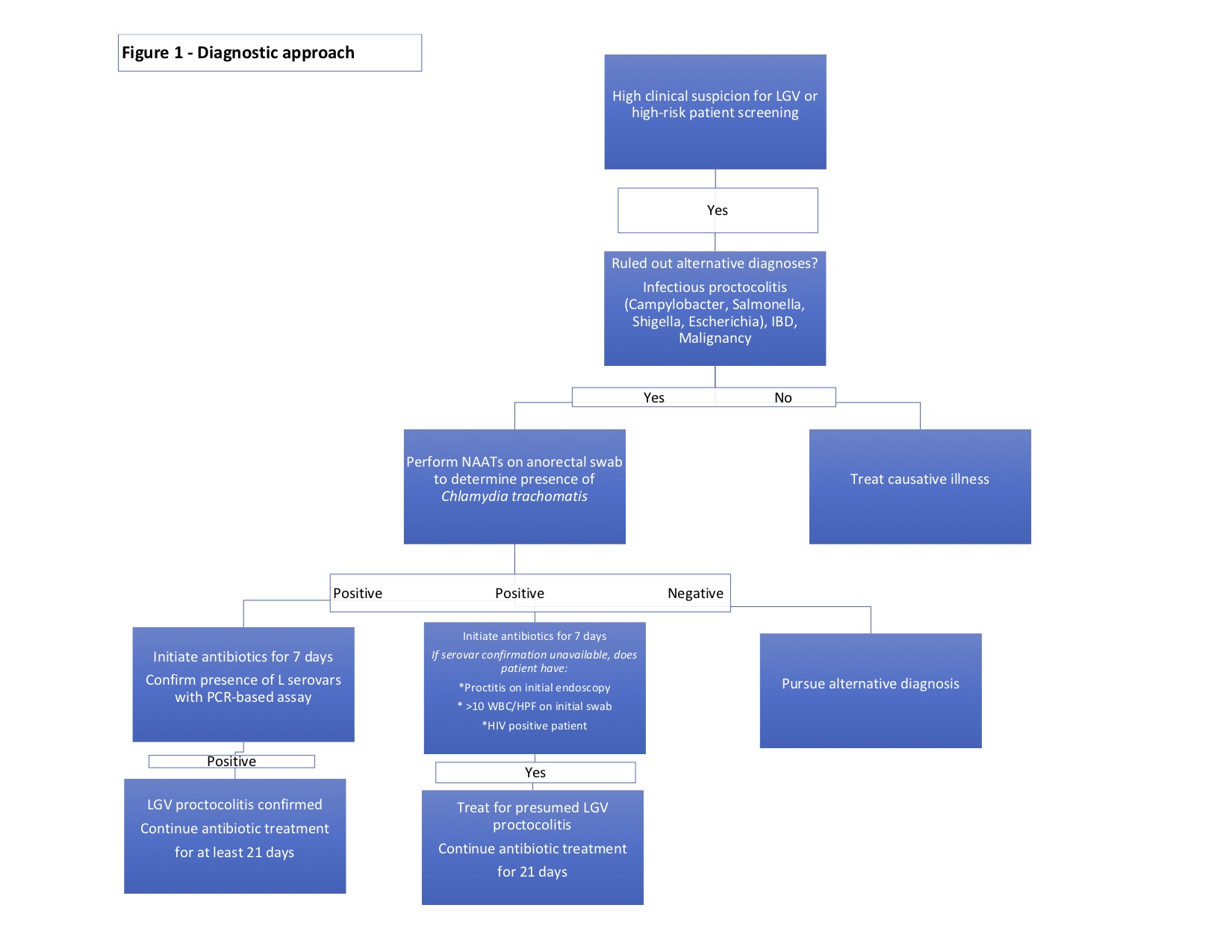

The diagnosis of LGV proctocolitis follows a stepwise approach. (Figure 1) Initial workup includes routine lab work, stool cultures to rule out more common infectious entities such as Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Escherichia, Clostridium. Cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic evaluation with sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy can help identify the extent of disease and any extraintestinal manifestations. An endoscopic biopsy can be utilized to rule out viral etiologies, malignancy, or underlying inflammatory conditions. As previously mentioned, endoscopic and histologic findings are often nonspecific and may mimic other disease processes.

When high clinical suspicion for LGV proctocolitis exists in a patient with known risk factors, attempts to isolate Chlamydia trachomatis should be performed. As Chlamydia trachomatis an intracellular organism, samples must contain cellular material, and routine bacterial smear and culture are insufficient to diagnose this organism.[16] Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) performed on swabs from the rectal mucosa, or anogenital lesions are the initial tests of choice.[22][23][24][25] NAAT techniques include PCR amplification, transcription-mediated amplification (TMA), or strand displacement amplification (SDA). All assays have high sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity from 91.4 to 100% and sensitivity from 98.3 to 98.8 depending on the NAAT technique employed).[26] Mandatory reporting of confirmed disease to the appropriate local agency is not required in all states but should be encouraged.

Following confirmation of infection, the recommendation is the identification of the L1-3 serovars. LGV biovar-specific DNA NAATs can be performed using the initial anorectal swab sample by PCR-based assays.[22][23][27] If positive, the recommended treatment is a 21-day course of antibiotics. Unfortunately, there is a lack of universal access to biovar specific confirmatory testing.[7] Where NAATs are unavailable, Chlamydia genus-specific serological assays such as complement fixation and L-type immunofluorescence are options, but these tests exhibit lower sensitivity and specificity. When serovar confirmation is unavailable, clinicians should consider initiating a 21-day course of antibiotic therapy in patients meeting one of the following criteria[16]:

- The presence of proctitis on initial colonoscopy

- More than ten white blood cells per high powered field on initial anorectal smear

- HIV positive

While these diagnostic strategies are important in symptomatic patients, they are also useful in screening asymptomatic, high-risk individuals who engage in receptive anal intercourse.

Treatment / Management

Current guidelines published by the CDC suggest treating patients with clinical features consistent with LGV infection such as proctocolitis or genital ulcer disease and lymphadenopathy.[28] The mainstay of therapy in LGV infection remains antibiotic use. Multiple sources, including the American and European guidelines, recommend first-line therapy with doxycycline 100 milligrams orally, twice daily, for 21 days. Erythromycin 500 milligrams orally, four times daily, can be used for second-line therapy and in pregnant patients.[28][29][30][31][32] Azithromycin 1 gram orally, once weekly for three weeks, is an attractive regimen that might improve patient compliance; however, no controlled trials presently support the efficacy of this therapy. All sexual partners should be screened to prevent reinfection and further spread of disease. Ultimately, prevention and the use of appropriate contraception are points of emphasis during encounters with at-risk patients.(A1)

A second approach is an option in patients with symptoms consistent with LGV proctocolitis. Clinicians can consider initiating empiric therapy with doxycycline 100 milligrams orally, twice daily for seven days in conjunction with ceftriaxone 250 milligrams once intramuscularly while lab tests are pending. If lab testing confirms Chlamydia infection, treatment should continue for a total of 21 days or as long as the patient manifests symptoms.[22](B2)

See Figure 1

Differential Diagnosis

- Primary LGV

- Diarrhea/pain - Infectious proctocolitis due to common organisms, other STIs such as Neisseria, CMV, HSV, amoebiasis

- Altered bowel habits, pain, bloody diarrhea - dysentery, inflammatory bowel disease

- Malignancy

- Pain and altered bowel habits - irritable bowel syndrome

- Rectal pain, bloody output - hemorrhoids

- Secondary LGV

- Constitutional symptoms, myalgias, arthralgias - routine infectious colitis, influenza

- Abnormal LFTs - hepatitis

- Malignancy - rectal carcinoma, lymphoma

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Tertiary LGV

- Fistula or stricture formation - inflammatory bowel disease - Crohn disease, Ischemic colitis

- C. difficile megacolon

- Malignancy

Prognosis

Prognosis is fair and hinges on prompt recognition of the condition, patient compliance with prolonged antibiotic therapy, and avoidance of high-risk behaviors. Recurrence is possible with repeat exposure.

Complications

Complications of prolonged infection are a result of ongoing, untreated infection. These complications signify progression to tertiary LGV and are characterized by colorectal strictures and stenoses, megacolon, lymphorrhea, fistulas, and chronic pelvic pain as a result of frozen pelvis syndrome.

Consultations

A multidisciplinary approach is often warranted. Consultation with infectious disease is necessary for HIV co-infected patients and those with refractory disease. Late stage illness may require surgical consultation if stricture, stenosis, fistulas, or megacolon develop.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Early recognition of the signs and symptoms of LGV is key to improving outcomes. Delays in diagnosis may be related to disease mimicry or failure to elicit an adequate sexual history from patients on intake. High-risk individuals should receive education on early signs and symptoms, means of transmission, prevention of transmission through safe sexual practices, and risks associated with having multiple sexual partners. Also, testing should be offered and considered in high-risk, asymptomatic patients, or those who present with other STIs.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Though high-risk populations more commonly present with LGV proctocolitis, it is crucial to remember that heterosexual patients can develop LGV proctocolitis through unprotected anal intercourse with an infected individual

- Asymptomatic, high-risk individuals may benefit from testing at routine visits at periodic intervals

- Partners of those infected with LGV should be tested and treated if positive for the disease

- Pregnant and lactating women should not be treated with doxycycline during the second and third trimester due to risk for discoloration of teeth and bones

- Instead, Erythromycin is first-line

- HIV co-infected individuals may experience a delay in resolution of the disease and may require prolonged courses of therapy

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The prevention and treatment of LGV proctocolitis will require a cooperative multispecialty approach, including nurses and clinicians, along with support from local outreach programs and government agencies. As was evidenced in the early 2000s, the ESSTI alert system in Europe was successful in providing clinicians with local alerts of disease activity and helped coordinate outbreak control. Since prompt recognition is critical, similar systems should be fostered in the United States, and clinicians should be encouraged to report to local agencies. As STIs continue to rise at alarming rates, clinicians across all specialties must continue to educate patients on safe sexual practices as well as how to identify the signs and symptoms of the disease. Initiating and supporting high-risk community outreach groups and screening initiatives for high-risk populations may reduce the stigma of testing and promote eradication. Overall, lifestyle choices, sexual preferences, and HIV co-infection remain the strongest risk factors for developing LGV. Frequent reiteration of safe practices by multiple providers across multiple specialties may reinforce the importance of and promote ongoing healthy patient practices. [Level V]

LGV infection diagnosis and management require an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, mid-level practitioners, specialists, specialty-trained nurses, and pharmacists, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level V] In most cases, the clinician (physician, NP, PA) will diagnose and prescribe treatment, although they will often require a close consult with infectious disease specialists. Pharmacists can verify agent antibiotic coverage and dosing, and report back to the nurse or clinician if they have any concerns. Nursing can dispense education and counseling to promote symptomatic recognition and/or preventative strategies; this should also have reinforcement from the physicians and the pharmacist. The pharmacist should also verify the patient's current regimen has no drug-drug interactions, and if there are any, let the nursing staff or clinicians know immediately. Nurses and pharmacists can both verify patient compliance and counsel patients on their medications or the dosing/administration of the same, and report any issues back to the prescribing clinician, who can make changes to the patient's drug regimen based on patient needs. These interprofessional strategies are the types that lead to optimal outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

COUTTS WE. Lymphogranuloma venereum; a general review. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1950:2(4):545-62 [PubMed PMID: 15434659]

Rönn MM, Ward H. The association between lymphogranuloma venereum and HIV among men who have sex with men: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC infectious diseases. 2011 Mar 18:11():70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-70. Epub 2011 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 21418569]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRichardson D, Goldmeier D. Lymphogranuloma venereum: an emerging cause of proctitis in men who have sex with men. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2007 Jan:18(1):11-4; quiz 15 [PubMed PMID: 17326855]

Macdonald N, Sullivan AK, French P, White JA, Dean G, Smith A, Winter AJ, Alexander S, Ison C, Ward H. Risk factors for rectal lymphogranuloma venereum in gay men: results of a multicentre case-control study in the U.K. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun:90(4):262-8. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051404. Epub 2014 Feb 3 [PubMed PMID: 24493859]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePallawela SN, Sullivan AK, Macdonald N, French P, White J, Dean G, Smith A, Winter AJ, Mandalia S, Alexander S, Ison C, Ward H. Clinical predictors of rectal lymphogranuloma venereum infection: results from a multicentre case-control study in the U.K. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun:90(4):269-74. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051401. Epub 2014 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 24687130]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoutin CA, Venne S, Fiset M, Fortin C, Murphy D, Severini A, Martineau C, Longtin J, Labbé AC. Lymphogranuloma venereum in Quebec: Re-emergence among men who have sex with men. Canada communicable disease report = Releve des maladies transmissibles au Canada. 2018 Feb 1:44(2):55-61 [PubMed PMID: 29770100]

Pathela P, Blank S, Schillinger JA. Lymphogranuloma venereum: old pathogen, new story. Current infectious disease reports. 2007 Mar:9(2):143-50 [PubMed PMID: 17324352]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Summary of notifiable diseases, United States 1995. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 1996 Oct 25:44(53):1-87 [PubMed PMID: 8926993]

Savage EJ, van de Laar MJ, Gallay A, van der Sande M, Hamouda O, Sasse A, Hoffmann S, Diez M, Borrego MJ, Lowndes CM, Ison C, European Surveillance of Sexually Transmitted Infections (ESSTI) network. Lymphogranuloma venereum in Europe, 2003-2008. Euro surveillance : bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin. 2009 Dec 3:14(48):. pii: 19428. Epub 2009 Dec 3 [PubMed PMID: 20003898]

Haar K, Dudareva-Vizule S, Wisplinghoff H, Wisplinghoff F, Sailer A, Jansen K, Henrich B, Marcus U. Lymphogranuloma venereum in men screened for pharyngeal and rectal infection, Germany. Emerging infectious diseases. 2013 Mar:19(3):488-92. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.121028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23621949]

Martí-Pastor M, García de Olalla P, Barberá MJ, Manzardo C, Ocaña I, Knobel H, Gurguí M, Humet V, Vall M, Ribera E, Villar J, Martín G, Sambeat MA, Marco A, Vives A, Alsina M, Miró JM, Caylà JA, HIV Surveillance Group. Epidemiology of infections by HIV, Syphilis, Gonorrhea and Lymphogranuloma Venereum in Barcelona City: a population-based incidence study. BMC public health. 2015 Oct 5:15():1015. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2344-7. Epub 2015 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 26438040]

Dougan S, Evans BG, Elford J. Sexually transmitted infections in Western Europe among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2007 Oct:34(10):783-90 [PubMed PMID: 17495592]

Brenchley JM, Price DA, Douek DC. HIV disease: fallout from a mucosal catastrophe? Nature immunology. 2006 Mar:7(3):235-9 [PubMed PMID: 16482171]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Nieuwkoop C, Gooskens J, Smit VT, Claas EC, van Hogezand RA, Kroes AC, Kroon FP. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctocolitis: mucosal T cell immunity of the rectum associated with chlamydial clearance and clinical recovery. Gut. 2007 Oct:56(10):1476-7 [PubMed PMID: 17872578]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen JC, Stephens RS. Trachoma and LGV biovars of Chlamydia trachomatis share the same glycosaminoglycan-dependent mechanism for infection of eukaryotic cells. Molecular microbiology. 1994 Feb:11(3):501-7 [PubMed PMID: 8152374]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCeovic R, Gulin SJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Infection and drug resistance. 2015:8():39-47. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S57540. Epub 2015 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 25870512]

Soni S, Srirajaskanthan R, Lucas SB, Alexander S, Wong T, White JA. Lymphogranuloma venereum proctitis masquerading as inflammatory bowel disease in 12 homosexual men. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2010 Jul:32(1):59-65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04313.x. Epub 2010 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 20345500]

Nieuwenhuis RF, Ossewaarde JM, Götz HM, Dees J, Thio HB, Thomeer MG, den Hollander JC, Neumann MH, van der Meijden WI. Resurgence of lymphogranuloma venereum in Western Europe: an outbreak of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar l2 proctitis in The Netherlands among men who have sex with men. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004 Oct 1:39(7):996-1003 [PubMed PMID: 15472852]

Roest RW, van der Meijden WI, European Branch of the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infection and the European Office of the World Health Organization. European guideline for the management of tropical genito-ulcerative diseases. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2001 Oct:12 Suppl 3():78-83 [PubMed PMID: 11589803]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKober C, Richardson D, Bell C, Walker-Bone K. Acute seronegative polyarthritis associated with lymphogranuloma venereum infection in a patient with prevalent HIV infection. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2011 Jan:22(1):59-60. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010262. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21364072]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePinsk I, Saloojee N, Friedlich M. Lymphogranuloma venereum as a cause of rectal stricture. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2007 Dec:50(6):E31-2 [PubMed PMID: 18067700]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVan der Bij AK, Spaargaren J, Morré SA, Fennema HS, Mindel A, Coutinho RA, de Vries HJ. Diagnostic and clinical implications of anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in men who have sex with men: a retrospective case-control study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2006 Jan 15:42(2):186-94 [PubMed PMID: 16355328]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Vries HJ, Zingoni A, White JA, Ross JD, Kreuter A. 2013 European Guideline on the management of proctitis, proctocolitis and enteritis caused by sexually transmissible pathogens. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2014 Jun:25(7):465-74. doi: 10.1177/0956462413516100. Epub 2013 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 24352129]

Morton AN, Fairley CK, Zaia AM, Chen MY. Anorectal lymphogranuloma venereum in a Melbourne man. Sexual health. 2006 Sep:3(3):189-90 [PubMed PMID: 17044226]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCusini M, Boneschi V, Arancio L, Ramoni S, Venegoni L, Gaiani F, de Vries HJ. Lymphogranuloma venereum: the Italian experience. Sexually transmitted infections. 2009 Jun:85(3):171-2. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.032862. Epub 2008 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 19036777]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBachmann LH, Johnson RE, Cheng H, Markowitz L, Papp JR, Palella FJ Jr, Hook EW 3rd. Nucleic acid amplification tests for diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis rectal infections. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2010 May:48(5):1827-32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02398-09. Epub 2010 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 20335410]

Morré SA, Spaargaren J, Fennema JS, de Vries HJ, Coutinho RA, Peña AS. Real-time polymerase chain reaction to diagnose lymphogranuloma venereum. Emerging infectious diseases. 2005 Aug:11(8):1311-2 [PubMed PMID: 16110579]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWorkowski KA, Bolan GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2015 Jun 5:64(RR-03):1-137 [PubMed PMID: 26042815]

Ward H, Martin I, Macdonald N, Alexander S, Simms I, Fenton K, French P, Dean G, Ison C. Lymphogranuloma venereum in the United kingdom. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007 Jan 1:44(1):26-32 [PubMed PMID: 17143811]

. National guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum. Clinical Effectiveness Group (Association of Genitourinary Medicine and the Medical Society for the Study of Venereal Diseases). Sexually transmitted infections. 1999 Aug:75 Suppl 1():S40-2 [PubMed PMID: 10616382]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. Drugs for sexually transmitted infections. The Medical letter on drugs and therapeutics. 2017 Jul 3:59(1524):105-112 [PubMed PMID: 28686575]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Vries HJ, Morré SA, White JA, Moi H. European guideline for the management of lymphogranuloma venereum, 2010. International journal of STD & AIDS. 2010 Aug:21(8):533-6. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010238. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20975083]