Introduction

Laryngotracheal injuries have a high mortality rate although they are infrequently seen. These injuries may be penetrating or blunt and can occur in the supraglottic, glottic, or infraglottic regions. Accurate and prompt recognition of laryngeal injury is essential, and different patterns and severity of injury are seen in blunt versus penetrating laryngeal trauma. Any patient presenting with a history of anterior neck trauma must be thoroughly assessed for the presence of a laryngeal injury and a safe airway confirmed, or established emergently, before proceeding with further workup.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Motor vehicle accidents are the primary cause of laryngeal injury, though the frequency has been dramatically reduced with the advent of seatbelts, airbags, and other advances in automotive safety equipment. Other causes include penetrating trauma, assault, attempted strangulation, near hanging, and clothesline-type injuries. Iatrogenic laryngeal injury can occur during bronchoscopy, emergent intubation, or percutaneous tracheostomy, and is discussed elsewhere in additional articles.

The larynx is typically protected from blunt trauma by the sternum and the mandible. Injury can occur when the neck is hyperextended due to trauma, such as in a rear-end automobile collision with a whiplash-type injury, or "clothesline"-type injuries where the exposed neck is impacted by a narrow-gauge object such as a tree branch or fence wire (often in the setting of motorcycle riding or snowmobiling), or when the larynx is intentionally targeted for damage during an assault (a direct strike to the neck to intentionally incapacitate the victim, or in strangulation). Penetrating neck injuries have a formal algorithm discussed in another article, and the larynx is at risk for injury. It is usually evident by history or by primary trauma survey whether a patient has sustained a blunt versus penetrating neck trauma, but it is wise to remain vigilant and have a very low threshold to secure a surgical airway in any case of anterior neck trauma.[1]

Epidemiology

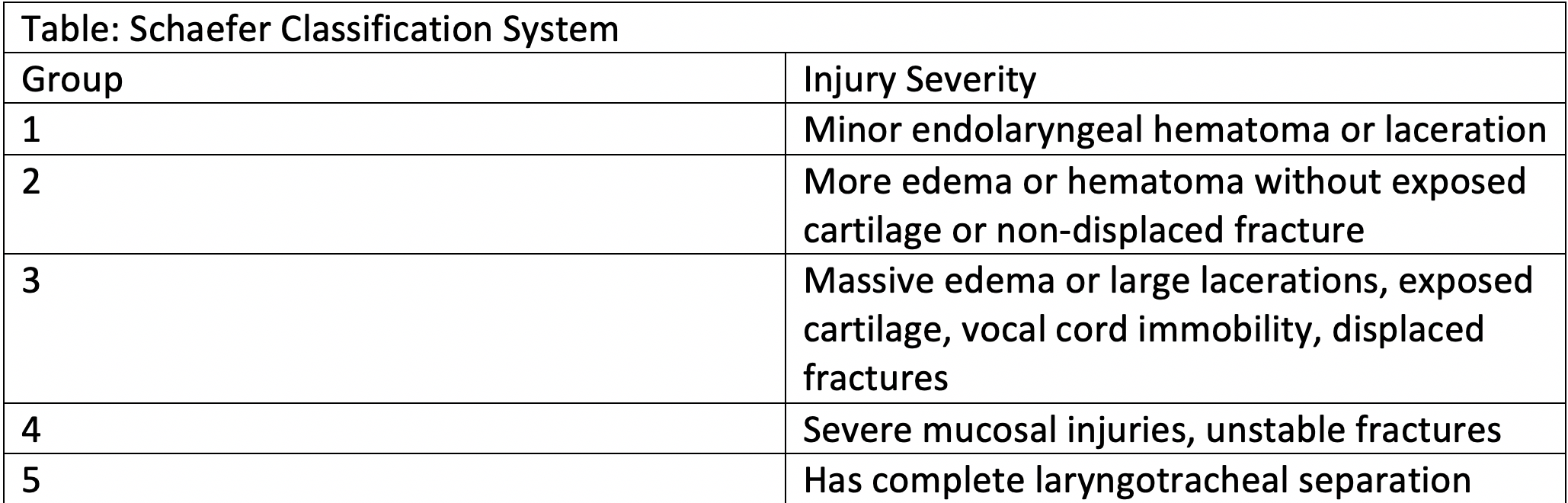

Injuries to the larynx account for less than 1% of all traumatic injuries. They are rare but can be very severe. It is a distant second-most common cause of death in patients with head and neck trauma after intracranial injuries. The Schaefer classification system is used to grade the severity of laryngeal injuries in some academic studies. This can provide a useful framework for the otolaryngologist or other physician evaluating an acute laryngeal injury.

Schaefer Classification

- Minor endolarygeal hematoma or laceration without fracture

- Severe edema, hematoma, non-displaced fracture or minor mucosal disruption without exposed cartilage

- Massive edema, large mucosal lacerations, displaced fractures or vocal cord immobilization, with exposed cartilage

- Severe disruption of the anterior larynx, unstable fractures, 2 or more fracture lines, and extensive mucosal injuries

- Complete laryngotracheal separation.[2]

In clinical practice, most providers sort patients into stable or unstable airway categories, as this has immediate implications regarding subsequent workup and examination. Unstable patients should have a definitive airway secured, usually via emergent tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy, prior to any additional workup. Stable patients may be further assessed via fiberoptic examination and/or imaging.

Pathophysiology

Blunt Laryngeal Injury

The degree of severity often corresponds to the force applied as well as the area over which it is applied. High-velocity injuries can fracture laryngeal and/or tracheal cartilages and lead to structural deformities of the larynx and trachea. The most severe case is the "clothesline" injury, and the classic scenario is a motorbike or snowmobile rider who strikes a small, stationary object such as a fence wire or tree branch that impacts the anterior neck below the helmet line. This applies significant forces over a small area and can lead to severe crushing injury to the laryngeal (and/or tracheal) cartilage resulting in airway obstruction. This can also lead to laryngotracheal separation due to shearing forces. Less severe blunt laryngeal injuries can be sustained during sports or fisticuffs and may cause submucosal endolaryngeal injuries due to shearing forces that may not be immediately obvious on external examination, or may cause hyoid fractures. Airway obstruction can result immediately due to structural deformities, or can present later as post-injury edema increases and patients become symptomatic due to delayed airway obstruction.

Penetrating Laryngeal Injury

The severity will again depend on the mechanism. Lower-velocity penetrating injuries such as knife wounds may be minimally symptomatic initially, but post-injury edema or hematoma may lead to airway compromise. High-velocity injuries such as firearms injuries (particularly high-velocity hunting or military rifle rounds) are uniformly devastating, fragmenting and destroying tissues of the larynx and surrounding structures. A relative devascularization and scarring of these tissues can cause significant long-term stenosis, in addition to any immediate airway concerns due to tissue disruption or post-injury edema.

History and Physical

The initial history is paramount in evaluating potential laryngeal injury. Any patient with a history of anterior neck trauma warrants a high degree of suspicion for laryngeal injury. This includes the mechanism of injury (blunt versus penetrating), time since injury, and other associated injuries. It is especially important to remember the potential for laryngeal injury in the poly-trauma patient such as an automobile accident, as the patient may not be coherent or cooperative.

Symptoms worrisome for laryngeal injury:

- History of anterior neck trauma

- Hoarseness or voice change

- Pain in the anterior neck

- Dyspnea

- Dysphagia

- Subcutaneous emphysema

Physical examination begins with an overall assessment of the patient's respiratory status. Remember the ABCs of trauma. Stridor may be inspiratory, expiratory, or biphasic, depending on the level of injury, and may or may not be accompanied by voice changes. All patients with neck trauma must be ruled out for concomitant cervical spinal injuries. Examination of the neck should include palpation for tenderness over the thyroid cartilage and trachea, loss of normal thyroid cartilage prominence, subcutaneous emphysema, ecchymoses over the anterior neck, and assessment of the voice for hoarseness if possible. Penetrating injuries should be obvious at this point, but seemingly innocuous findings externally can mask severe internal laryngeal injuries - a thorough examination is warranted in all cases. If the patient's airway is stable a flexible laryngoscopy should be performed to visualize the larynx and pharynx. If an obvious injury is identified, treatment should proceed. If patients are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic and have a normal flexible laryngeal exam, close observation is warranted. In patients with equivocal exams and a stable airway, particularly those with a worrisome history/mechanism of injury, computed tomography (CT) is warranted to more definitively characterize the laryngeal and tracheal structures. If this is deemed unsafe, or if clinical suspicion is high, the patient should be taken directly to the operating room for controlled endoscopic and bronchoscopic evaluation, and potential neck exploration and tracheostomy.

Evaluation

Flexible Laryngoscopy

This is the most important initial examination in a patient with an apparently stable airway. If there is any question as to the airway, proceed directly to tracheostomy/cricothyrotomy. After the primary and secondary trauma surveys are complete, flexible laryngoscopy assesses the internal mucosal structures of the larynx and upper aerodigestive tracts. This can identify edema (very common), as well as any laryngeal lacerations, hematomas, mucosal tears, or other structural abnormalities that may portend future complications. It will demonstrate the extent of mucosal injuries, if present, looking for exposed cartilage or vocalis muscle and examine the mobility of the vocal folds. New-onset vocal fold paresis is worrisome for occult laryngotracheal injury, and further workup should be initiated. The subglottis may be difficult to visualize in the acute setting. A normal flexible laryngeal exam is reassuring, though if the patient's symptoms and mechanism of injury are worrisome for occult injury, further workup may be required including bronchoscopy in the operating room. In an asymptomatic patient with a normal flexible laryngeal exam, intubation or tracheostomy may not be required before proceeding with imaging or further workup.

Computed Tomography (CT)

Imaging should be used very judiciously, and only if it is safe AND will affect the treatment algorithm. Patients with a reassuring history and clinical picture, AND a normal exam and laryngoscopy likely will not benefit from imaging. Similarly, those with an obvious injury will likely not benefit, as surgical intervention will be required. CT can be useful in those patients with a stable airway and a reassuring exam, but in whom clinical suspicion for undetected injury remains high. A non-contrasted CT of the neck can visualize the cartilaginous and bony structures of the larynx and hyoid, and highlight even subtle or nondisplaced fractures that may require stabilization.

Esophagram

There will be an associated esophageal injury in 4-6% of laryngeal fractures. Esophagram is not routinely used in the acute setting but may be useful in a delayed setting if a persistent injury is suspected. If there is suspicion of esophageal injury in the setting of laryngeal trauma, the optimal course of action is formal exam under anesthesia after securing the airway. This entails direct laryngoscopy and esophagoscopy, and may require open neck exploration in the operating room as well.

Chest X-ray (CXR)

This should be a matter of routine in the poly-trauma patient with a suspected neck injury and can usually be obtained with a portable roentgenogram if the patient is stable and protecting their airway. Subcutaneous emphysema on clinical exam may herald a chest wall in addition to, or rather than, a laryngotracheal injury.

Treatment / Management

The initial management of laryngeal injuries is to evaluate and establish an airway. The first decision point is "Is the airway stable?" If the patient is talking normally, the airway is at least patent, but may not be stable.[3] The following signs and symptoms increase the necessity of intubation, cricothyroidotomy, or tracheotomy: respiratory distress, neck hematoma, significant bleeding, subcutaneous neck emphysema, stridor, hoarseness, hemoptysis, thrill or bruit, and distorted neck anatomy. For those with obvious laryngeal fracture, stridor with increased work of breathing, or impending airway obstruction, tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy should be performed immediately.(B2)

In 2014 Schaefer reviewed 90 years of publications regarding acute laryngeal injuries.[4] He proposed the following management scheme based on this literature review and clinical experience:

Impending Airway Obstruction: Expert airway management resulting in tracheostomy, intubation, or cricothyrotomy. All patients are then evaluated with direct laryngoscopy and esophagoscopy. Treatment of findings after laryngoscopy and esophagoscopy should be as follows:

- Normal endolarynx or mucosal injury without fracture--Observation

- Thyroid or cricoid fracture with intact endolarynx--Neck exploration, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of laryngeal skeletal fractures with plating without thyrotomy.

- Unstable fractures or anterior commissure disrupted or major mucosal lacerations--ORIF of fractures, repair of mucosal lacerations and endolaryngeal stent or lumen keeper.

- Stable laryngeal fracture, anterior commissure intact, minor mucosal alterations--Neck exploration, ORIF of laryngeal skeletal fractures with plating thyrotomy, primary closure of lacerations.

Stable Airway: Flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy and computed tomography of the neck. Videostroboscopy of the larynx and electromyography of the larynx may also be used according to availability and local expertise. Treatment is dictated by the findings of these studies.

- Normal endolarynx with or without reversible mucosal injury without fracture--observation.

- Endolarynx or cartilage disruption--tracheostomy or intubation, direct laryngoscopy and esophagoscopy, neck exploration and repair of findings as under "impending airway obstruction."

- Treatment of airway injuries within 24 hours yields optimal results.

Medical Treatment/close Observation

For patients with Schaefer 1 and 2 injuries, close observation may be all that is required. This involves inhalational (nebulized) steroids as well as intravenous dexamethasone to combat edema. Serial flexible laryngoscopy and airway observation with pulse oximetry for at least the first 24 hours should be undertaken. In these injuries, where there is normal or near-normal mucosal coverage with minimal risk of untoward scarring of the larynx, this may be all that is required.

Surgical Treatment

All other cases will require surgical intervention, combined with rigorous examination under anesthesia of the larynx and esophagus via direct laryngoscopy and esophagoscopy, respectively. If there are only mild to moderate mucosal lacerations, endoscopic repair may be attempted to cover all cartilage and muscle and avoid scarring. Displaced or unstable fractures or significant mucosal lacerations will require open neck exploration with possible thyrotomy to repair. An "inside-out" approach should be utilized, with the mucosa repaired to ensure coverage and prevent scarring or webbing, followed by reduction and fixation of laryngeal fractures and repair of any esophageal injury. Finally, skin and soft tissue should be repaired. This approach should be tailored to the injuries present, and a formal thyrotomy may not be required if the intralaryngeal injuries are minor. If there are significant intralaryngeal mucosal injuries a stent may be required, though such devices should be used judiciously as they can actually create scarring as well.

Postoperatively these patients should be closely monitored in the intensive care unit for at least the first night. Many will require tracheostomy until the larynx has healed fully and its post-injury function can be formally assessed in conjunction with a speech pathologist. The patients should be fed via nasogastric or gastrostomy tube until the larynx has healed owing to a high risk of aspiration.

Differential Diagnosis

Vascular injury – may produce hemorrhage or hematoma, hypotension, and stroke symptoms. May also present as severe neck ecchymoses.

Pharyngoesophageal injury – produces blood in saliva, hematemesis, dysphagia/odynophagia, and hemoptysis; also may result in subcutaneous emphysema

Pneumothorax – respiratory distress

Prognosis

Laryngotracheal injuries have a potentially high mortality rate and require early definitive airway management. Missing a significant laryngeal injury can lead to airway obstruction and death. Patients with abrasions and/or small lacerations of the larynx or trachea are usually managed conservatively with close observation, serial scopes, and steroids. Patients with laryngeal fractures who receive early airway management have an improved recovery rate. Patients who receive early diagnosis and treatment have better vocal and airway outcomes.

Complications

Complications can range from the very mundane to devastating. Any intralaryngeal mucosal injury is likely to encounter some degree of granulation tissue as it heals. This will occasionally be very severe and lead to scarring, or (very rarely) an obstructive mass. Cicatrix formation is a dreaded complication, and rapid repair of the mucosa and avoiding exposed cartilage or muscle in the larynx is the best prevention. If scarring is persistent or severe, long-term tracheostomy dependence can result. Wound healing complications such as persistent tracheo- or laryngo-cutaneous fistulae are thankfully rare, but possible. Undetected esophageal injury is a potentially devastating complication. Vocal fold paralysis or paresis present at the presentation after injury will often recover, but can take up to one year to do so; there is a potential that such injury could be permanent and require further intervention. Similarly, the recurrent laryngeal nerve or superior laryngeal nerve could be injured during repair resulting is dysphonia or aspiration, and require subsequent management.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Hospitalization is required for observation in all laryngeal traumatic injuries. Some laryngotracheal injuries such as small mucosal injuries, nondisplaced fractures, and hematomas may be managed conservatively with elevation of the head, humidified air, analgesia, steroids, vocal rest, and clear diet.The long-term goal of treatment for these patients is to restore their swallowing mechanism and voice. More severe injuries may require prolonged speech and swallowing therapy, and there is apotential for longer-term tracheostomy or gastrostomy dependence. [5]

Consultations

Head and neck surgeons should be consulted in all suspected laryngeal injures to assist in the evaluation and management of laryngeal trauma. If such expertise is unavailable, a surgeon and anesthesiologist experienced in difficult airway management are essential. In the immediate, emergency, situation, if there is any question as to the stability of the airway an elective surgical airway should be performed (usually via awake tracheostomy) by the physician most experienced in such procedures.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with trauma to the neck whether sustained in a motor vehicle accident, gunshot, attempted hanging, knife to the neck, or assaults should present to the Emergency Department for evaluation as injuries to the larynx or trachea are serious and can result in death. Even if the person is currently asymptomatic, serious delayed complications may occur. In those patients having trouble breathing, a tracheostomy is usually required. Attempts at intubation should be avoided until a more formal picture of the upper airway is available; if this is not possible, a tracheostomy should be performed. Stable patients without significant trauma may need imaging, observation, or admission.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Laryngotracheal injuries are serious, have high mortality, and require airway management

- Airway compromise may be delayed

- Tracheostomy is the preferred airway

- Stable injuries may need additional imaging such as CT scan

- Unstable injuries need operative management

- Do not delay surgical consultation [6]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of a laryngeal injury requires multiple personnel to successfully resuscitate the patient. If an injury is suspected, nursing staff, respiratory therapist, emergency medicine physician and trauma surgeon will need to be involved. Communication about the trauma assessment should take place with emphasis of establishing an airway. In order to improve this, all equipment should be present immediately on patient's encounter to the ED including flexible fiberoptic scope in addition to airway kit and mechanical ventilation. [7]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kragha KO. Acute traumatic injury of the larynx. Case reports in otolaryngology. 2015:2015():393978. doi: 10.1155/2015/393978. Epub 2015 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 25821621]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoonsamy P, Sachdeva UM, Morse CR. Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2018 Mar:7(2):210-216. doi: 10.21037/acs.2018.03.03. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29707498]

Brennan J, Gibbons MD, Lopez M, Hayes D, Faulkner J, Eller RL, Barton C. Traumatic airway management in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2011 Mar:144(3):376-80. doi: 10.1177/0194599810392666. Epub 2011 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 21493199]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSchaefer SD. Management of acute blunt and penetrating external laryngeal trauma. The Laryngoscope. 2014 Jan:124(1):233-44. doi: 10.1002/lary.24068. Epub 2013 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 23804493]

Levine RJ, Sanders AB, LaMear WR. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis following blunt trauma to the neck. Annals of emergency medicine. 1995 Feb:25(2):253-5 [PubMed PMID: 7832358]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchaefer SD. The acute management of external laryngeal trauma. A 27-year experience. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 1992 Jun:118(6):598-604 [PubMed PMID: 1637537]

Butler AP, Wood BP, O'Rourke AK, Porubsky ES. Acute external laryngeal trauma: experience with 112 patients. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2005 May:114(5):361-8 [PubMed PMID: 15966522]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence