Introduction

The anterolateral aspect of the abdominal cavity, which holds multiple vital organs, is surrounded by an abdominal wall. This wall is made up of different layers that serve to protect the organs of the digestive system. These layers, from superficial to deep, include skin, Camper fascia, Scarpa fascia, external oblique muscle, internal oblique muscle, transversus abdominis muscle, transversalis fascia, and parietal peritoneum.

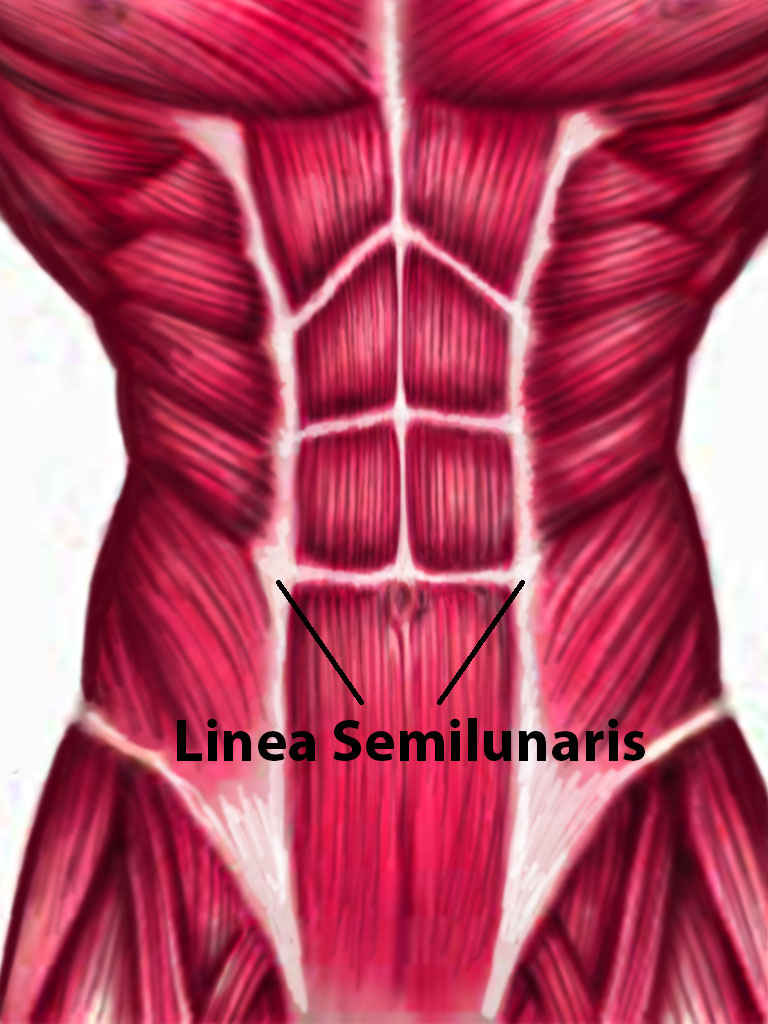

Linea semilunaris, sometimes referred to as the semilunar line or Spigelian line, makes the set of visibly well-developed abdominal muscles (also called as "six-pack") that athletes desire possible. This fibrous, pearly-white connective tissue is a type of aponeurosis that can function as fascia, which envelopes muscles and organs. It also binds the muscles in the anterolateral abdominal wall together.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The linea semilunaris is a vertical, curved structure that runs along the lateral edges of the rectus abdominis muscle in the anterior abdominal wall. It is the site of union where tendons of the lateral abdominal muscles meet the sheath surrounding the rectus abdominis muscle, also known as the rectus sheath. The lateral abdominal muscles are the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles.

Linea semilunaris runs between the cartilage of the ninth rib and the pubic tubercle bilaterally. The ninth ribs are farther apart from each other when compared to the pubic tubercles, which are closer together, giving the linea semilunaris its curved shape. Linea semilunaris provides strength, mobility, and flexibility to the lateral abdominal muscles. However, it is one of the weak areas of the anterior abdominal wall, and it is, therefore, susceptible to herniation.

Embryology

Embryonic differentiation gives rise to three separate layers: outer ectoderm, middle mesoderm, and inner endoderm. Mesoderm further differentiates into splanchnic mesoderm, which gives rise to abdominal viscera, and somatic mesoderm, which gives rise to the abdominal wall. By the end of the sixth week of gestation, muscle cells migrating from myotomes (a group of muscles innervated by a single nerve) into the somatic mesoderm on both sides of the vertebral column form the anterior abdominal wall muscles and their aponeuroses. Linea semilunaris also originates through this process.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply:

Anterior abdominal wall arteries and veins are responsible for the blood circulation of the linea semilunaris. The superior epigastric and musculophrenic arteries, both branches of the internal thoracic artery, supply the superior portion of the anterior abdominal wall. The inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac arteries, both branches of the external iliac artery, supply the inferior portion of the anterior abdominal wall.

The superior epigastric artery descends within the rectus sheath behind the rectus abdominis muscle. It is responsible for arterial blood supply to the upper portion of the muscle and the linea semilunaris. The inferior epigastric artery runs superiorly on the posterior surface of the rectus abdominis muscle and supplies the lower part of the muscle and the linea semilunaris. Additionally, small segmental branches that originate from the lower six intercostal arteries supply a portion of the rectus abdominis muscle and the linea semilunaris.[1] The arcuate line is a horizontal line that demarcates the inferior portion of the posterior rectus sheath and is also the point where inferior epigastric vessels pierce the rectus abdominis muscle.

Deep veins of the anterior abdominal wall superior to the umbilicus drain into the superior epigastric (medial) and musculophrenic (lateral) veins. These veins ultimately drain into the superior vena cava. Deep veins that are inferior to the umbilicus drain into the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac veins. These veins ultimately drain into the inferior vena cava.[2]

Lymphatics:

Lymphatic vessels superior to the umbilicus drain into the axillary lymph nodes, whereas lymphatic vessels inferior to the umbilicus drain into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes.

Nerves

Linea semilunaris is part of the anterior abdominal wall. Sensory and motor innervations to the muscles and connective tissues of the anterior abdominal wall derive from the anterior rami of the T7-T12 intercostal nerves. The anterolateral abdominal wall is supplied mainly by the thoracoabdominal, subcostal, lateral cutaneous, iliohypogastric, and ilioinguinal nerves.[3] Of relevance is the thoracoabdominal nerve, which derives from T7-T11. This nerve travels between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles then penetrates the rectus sheath at the linea semilunaris to supply the rectus abdominis muscle. It then terminates as the anterior cutaneous branches of the skin of the anterior abdominal wall. The passage of thoracoabdominal nerves through the rectus sheath at the linea semilunaris renders the linea semilunaris an undesirable site for incisions.

Muscles

Rectus abdominis is a long, paired vertical muscle located on either side of the midline. Its primary function is to flex the thoracic and lumbar spines. It consists of three horizontal lines called tendinous intersections that also contribute to the well-developed abdominal muscles seen in a fit athlete. The linea alba separates the right and left rectus abdominis muscles. Linea semilunaris forms the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscles bilaterally. The rectus sheath, which covers the rectus abdominis muscle, is comprised of both anterior and posterior layers. The anterior layer forms from aponeuroses of the external oblique and one-half of the internal oblique muscles. In contrast, the posterior layer forms from aponeuroses of the transversus abdominis and the other half of the internal oblique muscles.[4] The arcuate line is located about midway between the umbilicus and pubic symphysis and represents the inferior portion of the posterior rectus sheath. Therefore, below the arcuate line, only an anterior layer of the rectus sheath exists, and there is no posterior layer of the rectus sheath. There are oblique abdominal muscles on each side of the rectus abdominis muscle. The external abdominal oblique muscle is the most superficial and also the largest, the internal abdominal oblique muscle lies deeper, and the transversus abdominis muscle lies deepest.

Physiologic Variants

Many anatomical variations exist in the general population. Multiple variations in the anatomy of the anterior abdominal wall have been reported. These include variations in the arrangement of innervations to the rectus abdominis muscle and overlying skin, variations in the number and location of tendinous intersections of rectus abdominis muscles, variations in the shape and position of the arcuate line, and variations in the components of the anterior and posterior rectus sheaths.[5] Another common variation includes the presence or absence of accessory internal oblique or pyramidalis muscles.[5] Therefore, surgeons must have intricate knowledge of anatomy and variations in a region they are going to access.

The transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap procedure is a commonly used procedure for breast reconstruction. In this procedure, surgeons will create a free flap using both anterior abdominal wall tissue and the rectus abdominis muscle. These structures are disconnected from their blood supply in the abdomen and reconnected to the new blood supply in the chest. It is, therefore, imperative that surgeons are aware of the anatomy of the anterior abdomen, including variations in tendinous intersections and their blood supply. It is of particular importance because tendinous intersections are a site where many blood vessels anastomose.[6]

Surgical Considerations

Linea semilunaris is one of the weak points in the anterior abdominal wall. Therefore, this area is particularly susceptible to herniation of abdominal content or peritoneum. This hernia, known as a Spigelian hernia, has a relatively high risk of incarceration, and therefore surgical repair is recommended.[7][8]

Iatrogenic Spigelian hernias may also occur secondary to linea semilunaris damage caused when laparoscopic trocars or classic drains are inserted into Spigelian fascia.

Several different incisions can provide access to the abdominal cavity. These include midline/median, paramedian, transverse, Pfannenstiel, and subcostal incisions. In a "Paramedian Approach" to the abdominal cavity, linea semilunaris is the landmark usually used. In this approach, a vertical incision is made either in or lateral to the linea semilunaris, giving access to retroperitoneal structures. This approach has, however, fallen out of favor due to the risk of nerve injury and hematomas, as well as for cosmetic reasons.[9]

Clinical Significance

Spigelian fascia is a layer of aponeurosis located along the linea semilunaris, and it is comprised of both transversus abdominis and internal oblique aponeuroses. Rarely, a point of weakness may develop in the anterior abdominal wall fascia, particularly the Spigelian fascia, resulting in herniation of abdominal content or peritoneum through that fascia; this is known as a Spigelian hernia (SH), or a lateral ventral hernia.[7]

Spigelian hernias can occur anywhere along the linea semilunaris. They most often occur at or below the arcuate line due to the lack of posterior sheath at those levels. The incidence of Spigelian hernias ranges between 1 and 2% of abdominal hernias.[10] This type of hernia is seen mainly in females and in adults over 60 years of age. Risk factors include conditions that lead to increased intra-abdominal pressure or weakening of abdominal fascial layers. Examples include patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which causes chronic cough, patients with ascites secondary to liver cirrhosis, pregnant patients, or obese patients.[10]

The majority of Spigelian hernias occur on the right side, lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels. A Spigelian hernia may exist with ipsilateral cryptorchidism in 75% of male infants. This condition has the name Spigelian-cryptorchidism syndrome and is typically secondary to a congenital process.[11]

A Spigelian hernia presents as a palpable, painful or painless bulge along the linea semilunaris. The diagnosis is usually clinical. An ultrasound is the first-line imaging modality used if required.[12] The risk of incarceration is relatively high with Spigelian hernias. Therefore, and unlike other ventral hernias where conservative management is an option, surgical management is the mainstay of treatment for all patients with Spigelian hernias.

Media

References

Wade CI, Streitz MJ. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Abdomen. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31971744]

Joseph A, Scharbach S, Samant H. Anatomy, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Veins. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939686]

Jelinek LA, Scharbach S, Kashyap S, Ferguson T. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Fascia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083814]

Varacallo M, Scharbach S, Al-Dhahir MA. Anatomy, Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29262084]

Monkhouse WS, Khalique A. Variations in the composition of the human rectus sheath: a study of the anterior abdominal wall. Journal of anatomy. 1986 Apr:145():61-6 [PubMed PMID: 2962970]

Rai R, Azih LC, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Mortazavi M, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Tendinous Inscriptions of the Rectus Abdominis: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2018 Aug 4:10(8):e3100. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3100. Epub 2018 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 30338176]

Skandalakis PN, Zoras O, Skandalakis JE, Mirilas P. Spigelian hernia: surgical anatomy, embryology, and technique of repair. The American surgeon. 2006 Jan:72(1):42-8 [PubMed PMID: 16494181]

Baucom C, Nguyen QD, Hidalgo M, Slakey D. Minimally invasive spigelian hernia repair. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2009 Apr-Jun:13(2):263-8 [PubMed PMID: 19660230]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJelinek LA, Jones MW. Surgical Access Incisions. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082062]

Huttinger R, Sugumar K, Baltazar-Ford KS. Spigelian Hernia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855874]

Rushfeldt C, Oltmanns G, Vonen B. Spigelian-cryptorchidism syndrome: a case report and discussion of the basic elements in a possibly new congenital syndrome. Pediatric surgery international. 2010 Sep:26(9):939-42. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2681-7. Epub 2010 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 20680633]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmereczyński A, Kołaczyk K, Lubiński J, Bojko S, Gałdyńska M, Bernatowicz E. Sonographic imaging of Spigelian hernias. Journal of ultrasonography. 2012 Sep:12(50):269-75. doi: 10.15557/JoU.2012.0012. Epub 2012 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 26675533]