Introduction

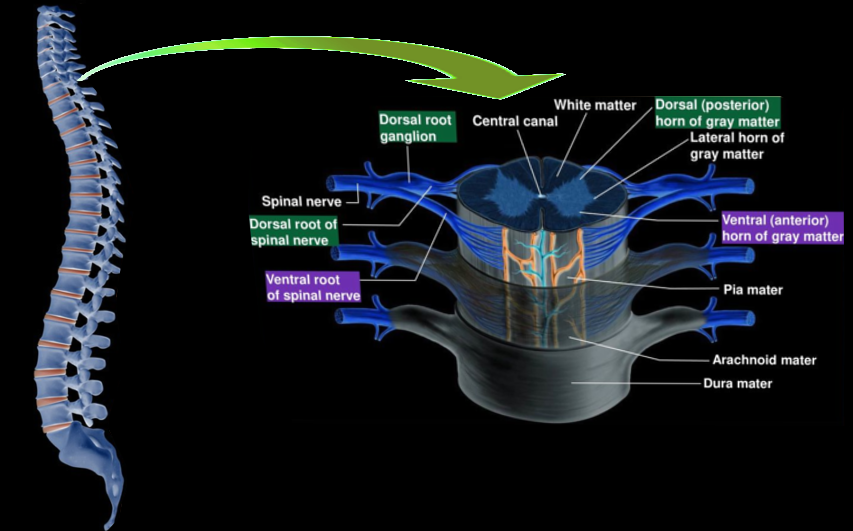

The spinal cord is a cylindrical well-organized structure. It begins at the foramen magnum as a continuation of the medulla oblongata at the base of the skull. It is located within the vertebral or spinal canal. In men, it extends up to 45 cm, and in women, up to 43 cm. The spinal cord divides into 31 segments: cervical 8, thoracic 12, lumbar 5, sacral 5, and coccygeal 1. These segments consist of 31 pairs of spinal nerves with their respective spinal root ganglia. Spinal nerves contain the motor, sensory, and autonomic fibers. These nerves exit through the intervertebral foramen. See Diagram. Nerve Fasciculi, Neurology, Principal Fasciculi of the Spinal Cord.

The vertebral column comprises seven cervical, twelve thoracic, and five lumbar segments. In adults, the cord terminates at the level of L1-L2. Thus the cord spans within 20 bony vertebrae. In a child, it terminates at the upper border of L3. Each of these segments innervates a dermatome. The spinal cord consists of both white matter and gray matter. The amount of white matter becomes sparse towards the end, and the gray matter converges to form the conus medullaris. The cord is anchored at the caudal end to the coccyx by the filum terminal, which is an extension of the pia mater. The spinal nerves L2 to S1 comprise the cauda equina present within the subarachnoid space called the lumbar cistern.

The spinal cord has two significant enlargements at the cervical and lumbar regions for brachial and lumbosacral plexus. In the thoracic region, the width of the spinal cord ranges between 0.64 to 0.83 cm, and in the cervical and lumbar regions, it ranges between 1.27 to 1.33 cm. The segment at C5 has the largest transverse diameter with 13.3 +/- 2.2 mm this decreases to 8.3 +/- 2.1 mm at T8, and it increases to 9.4 +/- 1.5 mm at L3. There is less variation in the anteroposterior diameter.[1][2][3][4]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Cross-section of the Spinal Cord

Both white matter and gray matter comprise the spinal cord. The gray matter is a collection of cell bodies, and the white matter is a collection of axons. The amount of gray matter is scarce at the thoracic levels as opposed to the cervical and lumbosacral segments. The spinal cord has fissures and sulci. The anterior median fissure is central, and the anterior white commissure is at its base. The posterior median sulcus is present posteriorly, and the posterolateral sulcus is present on either side of it. The anterior nerve roots exit at the anterolateral sulcus. The posterior nerve roots exit at the posterolateral sulcus.[1] The central canal runs between the two halves of the gray matter. It is continuous with the fourth ventricle and contains cerebrospinal fluid.

Internal Morphology of the Spinal Cord

Gray Matter

The transverse section through the spinal cord will display the gray matter in an H-shaped or butterfly pattern. It comprises neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, interneurons, glial cells (astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes), unmyelinated axons, and synapses.[5] See Diagram. Spinal Cord Morphology. The spinal cord gray matter can be differentiated into ten Rexed laminas I-X. Though Bror Rexed initially studied the spinal cord from a cat, it is essential to mention that this correlates well with all higher mammals. This data can be extrapolated and used to describe the human spinal cord. The following description will include studies from humans and other mammals. The laminae I-IX are organized from dorsal to ventral, while lamina X is located centrally around the central canal. This human spinal cord lamination pattern can be easily examined at the cervical and lumbar enlargements through the Golgi Impregnated sections or by Nissl staining. All the nuclei present in the spinal cord are a collection of cell bodies.

Dorsal Horn- Lamina I- VI

Lamina I (the marginal zone with the nucleus marginalis) is in the dorsal apex. This zone contains two types of cells; the Waldeyer cells, which are made up of medium or small neurons. The second type includes some large and easily recognizable cells in Nissl sections which are present near the point of entry of the dorsal roots.

Lamina II corresponds to the subtantia gelatinosa. It is made up of four types of neurons; they are the smallest cells in the dorsal horn. They have an abundance of dendrites. The Waldeyer cell dendrites from lamina I and interneurons also penetrate this layer.

Function: The axons carrying the noxious and temperature impulses from the peripheral receptors will synapse at both the lamina I and II. They will then cross the midline via the anterior white commissure and ascend via the lateral spinothalamic tract.

Lamina III has nerve cells that are uniform, large, pale cells with a light nucleus and a prominent nucleolus. They have less amount of Nissl substance. They have comparatively larger cells than lamina II.

Lamina IV contains cells that are not uniform but are a conglomeration of different sizes of cells. The presence of large cells and small cells adjacent to each other is characteristic of lamina IV. The lateral end of the lamina IV does not show a bend that is present in the first three laminas.

Function: Lamina III and IV correspond to the nucleus proprius. The spinothalamic tract synapses here. These two laminas aids in the processing of vibration and pressure touch sensations. They carry conscious proprioceptive impulses to the cerebral cortex via the dorsal medial lemniscus pathway.

Lamina V is the most diverse lamina in the dorsal horn made up of ten neuron types and has the most dendritic interconnections. Across the dorsal cell column, this lamina has two zones called the medial and lateral zone. The lateral zone is reticulated and has darkly staining cells. The medial zone has light cells.

Function: Sensory afferents received from cutaneous, muscle, mechanical, and visceral nociceptors get processed in Lamina V.

Lamina VI is in the basal region of the dorsal cell column. This area subdivides into the medial zone that consists of compactly arranged small cells and the lateral zone with loosely arranged, larger star-shaped cells. They correspond to the central parts of the nuclei of Cajal.

Function: Flexion reflex, which is reflex withdrawal from painful stimuli, is processed by lamina VI. They will receive information from the muscle spindles. They function together with lamina VIII to coordinate the spinal reflexes within the spinal cord.

Lateral Horn- Lamina VII

Lamina VII is present in the lateral gray horn. The lateral horn is present only from T1-L2. Above and below these segments, it extends into the anterior gray horn.

Lamina VII and X are called the intermediate gray zone, which subdivides into a medial zone made up of interneurons and propriospinal neurons. This medial zone aids in reflexes, autonomic functions, and movement. The lateral zone is made up of multiple tract neurons and aids in posture and movement. Lamina VII has the dorsal nucleus of Clarke, which is present from C8-L3. This medially located nucleus gives origin to the ipsilateral spinocerebellar tract. They carry unconscious proprioception via the spinocerebellar tract to the cerebellum. The intermediolateral nucleus is present laterally from T1-L2. It is composed of preganglionic sympathetic neurons that send impulses to the face, neck, heart, and abdominal organs. They also contain preganglionic parasympathetic neurons between the segments S2-S4, which sends impulses to the pelvic and few abdominal organs. The sympathetic ganglion chain, which is part of the sympathetic system, is present adjacent to the spinal cord. The chain receives axons from the intermediate gray horn, which synapse within the ganglion and ascend or descend to reach the target organs. Horner syndrome is a pathology due to compression of the sympathetic chain.

Ventral Horn- Lamina VIII- IX

The cervical and lumbosacral segments have a large ventral gray horn for the brachial and lumbosacral plexus—these plexus supply the upper and lower limb extremities.

Lamina VIII contains heavily staining nerve cells and has a heterogeneous appearance. They contain a moderate amount of Nissl substance, which has a granular appearance, although they have less Nissl substance than lamina IX. They are mostly triangular or star-shaped. It is composed of interneurons and proprioceptive neurons. They function along with lamina VI to process the reflex pathway. The reflex pathways are processed unconsciously within the spinal cord independent of the cortex.

The vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts synapse in lamina VIII.

Lamina IX is not a true lamina. It is a set of columns in the lamina VII and VIII. The cells have an abundance of Nissl substance.

The medial motor column innervates the proximal muscles, such as the deep back muscles, the prevertebral neck region, intercostal, and anterior body wall muscles.

The lateral motor column is present only in the lumbar and cervical enlargements. It innervates the distal muscles, which include the extremity, shoulder, and pelvic girdle muscles.

The central motor column has the accessory nucleus from C1-C5, the phrenic nucleus from C3-C5, and the lumbosacral nucleus from L2-S1.

Central Zone- Lamina X

Lamina X is located centrally around the central canal. They consist of axons that cross to the opposite side of the cord.[1][3][6][7][8]

White Matter

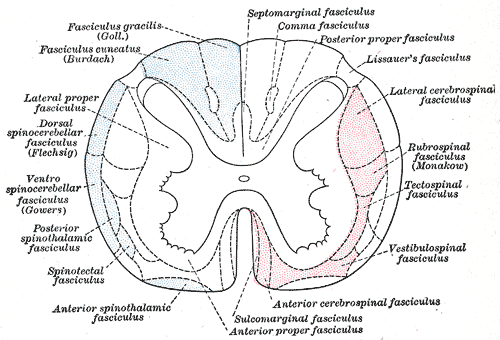

White matter surrounds the gray matter and is formed by tracts that transmit information up and down the spinal cord; this divides into 3 funiculi.

The Anterior Funiculus lies between the two anterolateral sulcus and the anterior median fissure.

The Posterior Funiculus is between the posterolateral and posterior median sulcus.

The Lateral Funiculus is between the anterior and posterior roots.

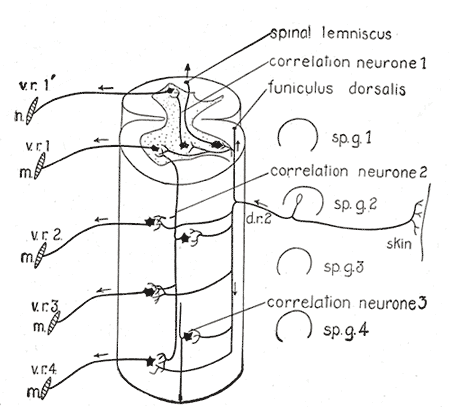

The cord segments have a dorsal root or the sensory ganglia. It contains cell bodies for the sensory pathway. They are pseudounipolar nerve cells with a long process coming from the peripheral receptors and a short process that will enter the spinal cord to reach the dorsal horn.

Ascending Fiber System

The Dorsal Column-Medial Lemniscus System or The Posterior Column comprises laterally located fasciculus cuneatus and medially located fasciculus gracilis (see Diagram. Central Connections of the Spinal Cord). They receive afferent impulses from C1 to T6 and from below T6, respectively. Thus the cuneate fasciculus relays information from the upper limb extremities and upper thoracic spine, and the gracile fasciculus relays information from the lower limb extremities and mid-thoracic spine. There is a single dorsal column in the lumbar segments of the cord where only the gracile tract is present; there are no subdivisions. The dorsal column has two subdivisions only from the cervical segments of the cord.

The axons for this tract originate as primary neurons from the ipsilateral dorsal root ganglion and travel upward to synapse at their corresponding nuclei in the lower medulla. Postsynaptically, internal arcuate fibers are formed, which decussate to the medial lemniscus. They then synapse at the ventral posterolateral nucleus of the thalamus and finally at the sensory cortex.

Function: They transmit vibration sense; position sense is also called proprioception and two-point discrimination. Multiple pathologies, such as vitamin B12 deficiency or tabes dorsalis, can affect this tract, selectively damaging the dorsal column.

The Spinothalamic Tract is also referred to as the anterolateral system. The ventral spinothalamic tract transmits crude touch and pressure sensations, and the lateral spinothalamic tract transmits pain and temperature sensations.

The impulses from the periphery reach the dorsal root ganglia and then enter the spinal cord in the Lissauer tract. Lissauer's dorsolateral tract carries pain and temperature sensation. This tract travels short distances of 1-2 segments. The impulse ascends or descends within the Lissauer tract to synapse commonly at the lamina II of the dorsal horn. Postsynaptically their axons cross to the contralateral side through the anterior white commissure and ascend to synapse at the thalamus, then terminate at the postcentral gyrus.

The Spinocerebellar Tracts are located at the lateral funiculus. Anteriorly the ventral spinocerebellar tract is lateral to the anterolateral system, and posteriorly the dorsal spinocerebellar tract is lateral to the corticospinal tract. They carry unconscious proprioceptive information from the muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs to the cerebellum.

The other ascending tracts are the spinoreticular tract, spinoolivary tract, spinomesencephalic tract, and spinohypothalamic tract.

Descending Fiber System

The corticospinal Tract originates from the precentral motor cortex. It includes two components, the lateral corticospinal tract, comprised of 90% crossed fibers, and the anterior corticospinal tract, which is 10% uncrossed fibers. They decussate at the lower medulla. They are named pyramidal tracts as the tract travels through the pyramids of the medulla. The lateral corticospinal tract is present in the lateral funiculi. It is medially adjacent to the dorsal spinocerebellar tract. Some of the uncrossed fibers of the anterior corticospinal tract cross via the anterior white commissure to the contralateral side interneurons and lower motor neurons. The anterior corticospinal tract is present close to the anterior median fissure, mostly in the upper segments of the spinal cord, which gradually diminishes as we go towards the lower segments of the cord. They innervate the postural muscles. The size of the corticospinal tract gradually shrinks towards the lower segments of the cord. They directly innervate the motor neurons of the spinal cord, unlike the extrapyramidal tract, which modulates the action indirectly. The fibers that carry impulses to the upper extremities (cervical) are present centrally, and the fibers that carry impulses to the lower extremities (lumbosacral region) are present laterally.

Function: It provides impulses responsible for the limb and axial body movement, carrying motor information for voluntary movement.

The Extrapyramidal Tract is crucial for involuntary movements. It mostly occurs in the anterior portion of the cord and functions by indirectly controlling the anterior motor horn cells. Together, it helps maintain changes in posture, muscle tone, and reflexes.

The rubrospinal tract primarily arises from the red nucleus on the contralateral side of the brainstem, and they descend anterior to the corticospinal tract. This tract is commonly involved with modulating the flexor movements, predominantly the proximal muscles of the upper limbs. This tract is responsible for the characteristic decorticate posture (abnormal flexion reaction of upper limbs and extension of the lower limbs) in response to a painful stimulus following trauma. Due to the trauma, the red nucleus becomes disinhibited. Thus, the rubrospinal tract sends impulses to the upper limbs to cause flexion, overshadowing the tracts that usually oppose and balance with extension. The extension of the lower limb is due to the additional disruption of the corticospinal tract leading to imbalance. The vestibulospinal tract originates from the brainstem vestibular nuclei. These fibers go to the alpha motor neurons via the interneurons. Their primary function is maintaining tone and posture by sending impulses to the extensor and antigravity muscles. The reticulospinal tract helps control muscle spindles; this is essential for the bilateral coordination of both postural and locomotion muscles. The tectospinal tract provides neural impulses to the ventral gray interneurons. This tract controls reflex head movement in response to sudden external stimuli such as auditory, tactile, and visual.[1][3]

Embryology

During spinal cord development, the three layers called the marginal, mantel, and matrix layers can differentiate after the neural tube closes.

The marginal layer becomes the zone of peripheral white matter fibers.

The anterior mantle Layer, also called the basal plate, expresses The sonic hedgehog, which induces the development of the motor area anteriorly as the ventral gray horn. The alar plate expresses bone morphogenic proteins and Wnt factors, which will induce the development of the sensory area posteriorly as the dorsal gray horn.

The matrix layer, located around the central canal, comprises neuroblasts that will migrate up to the mantle layer. This zone in between becomes the periventricular gray matter.

The spinal ganglia derived from the neural crest cells will form bipolar cells and will carry sensory input.[3][9]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial Supply

The spinal cord is a vital, fundamental part of the central nervous system and has adequate blood supply and anastomosis. Cervical and lumbar enlargements have additional blood flow. The anterior spinal artery and a pair of posterior spinal arteries supply the spinal cord.

The anterior spinal artery supplies the anterior two-thirds of the cord.

The posterior spinal arteries give vascular supply to the posterior one-third of the cord. These arteries arise from the distal vertebral arteries though some variations may exist. The three vessels anastomose around the cord to form the pial plexus, also called the vasocorona, provide a robust blood supply to the spinal cord.

The artery of Adamkiewicz, which is the largest radiculomedullary artery, supplies the lumbar cord.[10]

Venous Drainage

The spinal venous system is a valveless venous system composed of three intercommunicating drainage systems. The systems drain into the extra spinal veins, which ultimately reach the heart.

The collecting veins are called the intrinsic venous system. They divide into central and peripheral veins. The central veins drain the anterior horn medially, the white matter of the ventral commissure, the anterior funiculus, gray commissure, and white matter dorsally. The peripheral radial veins drain the remaining areas of the spinal cord.

The extrinsic venous system comprises the pial venous network, radicular veins, anterior, and posterior spinal veins. The great anterior radiculomedullary vein, which is commonly mistaken for the artery of Adamkiewicz, drains the thoracolumbar cord.

The extradural venous system comprises the Batson plexus, also called the vertebral venous plexus. They drain the spinal cord and the vertebral column.[11]

Surgical Considerations

Cauda Equina and Conus Medullaris Syndrome: Early surgical decompression within 24 hours must occur to avoid permanent neurological deficits in these syndromes.

Intervertebral Disc Herniation: Discectomy can be done to relieve the compression on the spinal cord when the symptoms are too severe.

Lumbar Puncture is a procedure to obtain cerebrospinal fluid from the subarachnoid space for analysis, which can help diagnose a patient. The needle is passed between the segments L3 to L5. This procedure is commonly used to diagnose meningitis, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and other neurological disorders, such as multiple sclerosis and Guillain-Barre syndrome.

Clinical Significance

Spinal cord injuries are categorized into six syndromes.

1. Brown-Sequard Syndrome

This accounts for 1 to 4 % of the traumatic spinal cord injuries. There are two types of presentations: the pure Brown-Sequard syndrome and the Brown-Sequard syndrome plus. The prognosis is the same.

Etiology- Commonly penetrating stab injuries, other causes are blunt injuries, neoplasia, vascular, and cord herniation.

Clinical Presentation

At the level of lesion: Ipsilateral flaccid paralysis due to anterior horn injury and a complete loss of sensation at that dermatome due to the posterior horn injury.

Below the level of lesion: Ipsilateral upper motor neuron lesion leading to spastic paraparesis due to lateral corticospinal tract injury, and loss of vibration and proprioceptive sensations due to posterior column lesion.

Contralateral to the side of injury: loss of pain and temperature sensations due to the spinothalamic tract injury that begins a few segments below the lesion.[12][13]

2. Central Cord Syndrome

This is the most common of all the spinal cord injury syndromes and accounts for 9%.

Etiology; Commonly occurs in older patients who experience hyperextension injury with comorbid cervical spondylosis. The cord is compressed between the bone spur and inward budging of the ligamentum flavum. Other causes include falls, motor vehicle accidents.

Clinical Presentation

The patients have more upper limb involvement relative to the extent of the lower limb involvement. Bladder involvement and loss of sensation below the level of the lesion can be seen.[13][14]

3. Posterior Cord Syndrome

This is the least common and accounts for less than 1%.

Etiology- Trauma, vitamin B12 deficiency leading to subacute combined degeneration of the cord, multiple sclerosis caused by demyelination, tabes dorsalis, vascular occlusions.

Clinical Presentation

There is sensory impairment leading to loss of touch, proprioceptive, and vibratory sensation below the lesion level as the dorsal column is involved. Pain, temperature sensation, and motor functions are spared. They will have a positive Romberg test with sensory ataxia.[3][13]

4. Anterior Cord Syndrome

This has the worst prognosis compared to the other injuries.

Etiology - The anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord is a watershed zone, thus inadequate vascular supply due to occlusion of the anterior spinal artery. Emboli, post-surgery complications, or hypotension can cause this. Unlike posterior cord syndrome, flexion injuries can also cause this syndrome.

Clinical Presentation

Motor function is affected due to the corticospinal tract and anterior horn involvement. Pain and temperature sensation is impaired at or below the lesion due to spinothalamic tract involvement. Autonomic presentation such as sexual dysfunction; bladder, and bowel dysfunction is due to intermediate gray zone injury.[3][13][15]

5. Cauda Equina Syndrome

This is rare, with 1% to 5 % incidence of all spinal pathologies. There is a compression of the spinal nerves and spinal nerve roots of the cauda equina, especially the lumbar segments. The cord is spared.

Etiology- Lumbar disc herniation, trauma, abscess, tumors.

Clinical Presentation

They will present as a lower motor neuron lesion causing flaccid paralysis with lower limb weakness, numbness, tingling, bladder, and bowel dysfunction. On examination, there may be areflexia, variable perineal anesthesia, decreased sphincter tone, and absent anal reflex.It is strongly recommended to decompress within 24 hours from the time of presentation to avoid residual dysfunction.

This syndrome is commonly misunderstood as conus medullaris syndrome as they have overlapping clinical presentations. However, cauda equina syndrome is a lower motor neuron lesion as the cord is spared, as opposed to conus medullaris syndrome, where upper motor neuron signs such as spasticity and hyperreflexia are present.[16]

6. Conus Medullaris Syndrome

It is characterized by damage to the sacral cord called the conus medullaris and lumbar roots within the vertebral canal.

Etiology: Trauma and tumors

Clinical Presentation

Lower extremity spastic paresis, hyperreflexia, saddle anesthesia. Bladder and bowel dysfunction may be present. The presentation can include both upper and lower motor neuron signs. Early decompression surgery must be done to avoid poor outcomes during recovery.[13][17]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Nerve Fasciculi, Neurology. The illustration depicts the principal fasciculi of the spinal cord.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Central Connections of the Spinal Cord. This illustration portrays a diagram of the spinal cord reflex apparatus, spinal lemniscus, correlation neurone, and funiculus dorsalis.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bican O, Minagar A, Pruitt AA. The spinal cord: a review of functional neuroanatomy. Neurologic clinics. 2013 Feb:31(1):1-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.09.009. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23186894]

Frostell A, Hakim R, Thelin EP, Mattsson P, Svensson M. A Review of the Segmental Diameter of the Healthy Human Spinal Cord. Frontiers in neurology. 2016:7():238. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2016.00238. Epub 2016 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 28066322]

Diaz E, Morales H. Spinal Cord Anatomy and Clinical Syndromes. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2016 Oct:37(5):360-71. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2016.05.002. Epub 2016 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 27616310]

Adigun OO, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Back, Spinal Cord. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725689]

Gaudet AD, Fonken LK. Glial Cells Shape Pathology and Repair After Spinal Cord Injury. Neurotherapeutics : the journal of the American Society for Experimental NeuroTherapeutics. 2018 Jul:15(3):554-577. doi: 10.1007/s13311-018-0630-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29728852]

REXED B. The cytoarchitectonic organization of the spinal cord in the cat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1952 Jun:96(3):414-95 [PubMed PMID: 14946260]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceREXED B. A cytoarchitectonic atlas of the spinal cord in the cat. The Journal of comparative neurology. 1954 Apr:100(2):297-379 [PubMed PMID: 13163236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbdel-Maguid TE, Bowsher D. The grey matter of the dorsal horn of the adult human spinal cord, including comparisons with general somatic and visceral efferent cranial nerve nuclei. Journal of anatomy. 1985 Oct:142():33-58 [PubMed PMID: 17103589]

Ludwig PE, Reddy V, Varacallo M. Neuroanatomy, Central Nervous System (CNS). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28723039]

Kaiser JT, Reddy V, Lugo-Pico JG. Anatomy, Back, Spinal Cord Arteries. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725904]

Green K, Reddy V, Hogg JP. Neuroanatomy, Spinal Cord Veins. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194339]

Roth EJ, Park T, Pang T, Yarkony GM, Lee MY. Traumatic cervical Brown-Sequard and Brown-Sequard-plus syndromes: the spectrum of presentations and outcomes. Paraplegia. 1991 Nov:29(9):582-9 [PubMed PMID: 1787982]

McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, Brooke K. Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2007:30(3):215-24 [PubMed PMID: 17684887]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTow AM, Kong KH. Central cord syndrome: functional outcome after rehabilitation. Spinal cord. 1998 Mar:36(3):156-60 [PubMed PMID: 9554013]

Klakeel M, Thompson J, Srinivasan R, McDonald F. Anterior spinal cord syndrome of unknown etiology. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center). 2015 Jan:28(1):85-7 [PubMed PMID: 25552812]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKennedy JG, Soffe KE, McGrath A, Stephens MM, Walsh MG, McManus F. Predictors of outcome in cauda equina syndrome. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 1999:8(4):317-22 [PubMed PMID: 10483835]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRider LS, Marra EM. Cauda Equina and Conus Medullaris Syndromes. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725885]