Introduction

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is a condition in which there is an increase in left ventricular mass, either due to an increase in wall thickness or due to left ventricular cavity enlargement, or both. Most commonly, the left ventricular wall thickening occurs in response to pressure overload, and chamber dilatation occurs in response to the volume overload.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are various clinical conditions that can lead to the development of LVH. The most common of these include the following:

- Essential hypertension

- Renal artery stenosis

- Athletic heart with physiological LVH

- Aortic valvar stenosis

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without or with outflow tract obstruction (HOCM)

- Subaortic stenosis (left ventricular outflow tract obstruction by muscle or membrane)

- Aortic regurgitation

- Mitral regurgitation

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Ventricular septal defect

- Infiltrative cardiac processes (e.g., Amyloidosis, Fabry disease, Danon disease)

Hypertension and aortic valve stenosis are the most common causes of LVH. In both of these conditions, the heart is contracting against an elevated afterload. Another cause is increased filling of the left ventricle inducing diastolic overload, which is the underlying mechanism for eccentric LVH in patients with regurgitant valvular lesions such as aortic regurgitation or mitral regurgitation and also seen in dilated cardiomyopathy. Coronary artery disease has been demonstrated to play a role in the pathogenesis of LVH, as the normal myocardium tries to compensate for tissue that has become ischemic or infarcted. Athletic heart with physiological LVH is a relatively benign condition. Intensive training results in increased left ventricular muscle mass, wall thickness, and chamber size, but the systolic function and diastolic function remain normal.

Epidemiology

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) is present in 15% to 20% of the general population. It is more often prevalent in blacks, the elderly, the obese, and in patients with hypertension.[1]. A review of echocardiographic data of 37700 individuals revealed 19%-48% prevalence of LVH in untreated hypertensives and 58%-77% in high-risk hypertensive patients. The presence of obesity also causes 2 -fold increased risk of developing LVH. The prevalence of LVH ranges from 36% (conservative criteria) to 41% (lesser conservative criteria) in the population, depending on the criteria used for defining it. LVH prevalence is not reported to be different between men and women (range 36.0% versus 37.9% (conservative criteria) and 43.5% versus 46.2% (lesser conservative criteria).The prevalence of eccentric LVH is relatively more compared to concentric hypertrophy.[1]

Pathophysiology

Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and remodeling early on, are very important compensatory processes that develop over time in response to wall stress or any significant hemodynamic pressure or volumetric burden. The increased mass of muscle fibers or wall thickness serves initially as a compensatory mechanism that helps to maintain contractile forces and counteracts the increased ventricular wall stress. The benefits of increased wall thickness to compensate for elevated wall stress are offset by a significant increase in the degree of stiffness of the hypertrophied walls associated with a significant increase in diastolic ventricular pressures, which are subsequently transmitted back into the left atrium as well as the pulmonary vasculature.

As previously indicated, LVH is a compensatory but ultimately, an abnormal increase in the mass of the myocardium of the left ventricle induced by a chronically elevated workload on the heart muscle. But, pathologic LVH once developed, puts the patient at significant risk for the development of heart failure, dysrhythmias, and sudden death. The most common etiologic cause is the heart contracting against an elevated afterload, as seen in hypertension and also seen in valvar aortic stenosis. Another cause is increased filling of the left ventricle inducing diastolic overload, which is the underlying mechanism for eccentric LVH in patients with regurgitant valvular lesions such as aortic regurgitation or mitral regurgitation and also seen in dilated cardiomyopathy. Coronary artery disease has been demonstrated to play a role in the pathogenesis of LVH, as the normal myocardium tries to compensate for tissue that has become ischemic or infarcted. One key pathophysiologic component in LVH is the concomitant development of myocardial fibrosis. Initially, fibrosis is clinically manifested by diastolic dysfunction, but systolic dysfunction will also develop with progressive disease.[2]

Based on relative wall thickness (posterior wall thickness x 2 / LV internal diameter at end-diastole), and the left ventricular mass (LVM) index (left ventricular mass normalized for body surface area or height), the left ventricular hypertrophy can be categorized into 2 types; concentric hypertrophy (increased LWM index and relative wall thickness (RWT) more than 0.42) or eccentric hypertrophy (increased LWM index and RWT less than or equal to 0.42).

Concentric left ventricular hypertrophy is an abnormal increase in left ventricular myocardial mass caused by chronically increased workload on the heart, most commonly resulting from pressure overload-induced by arteriolar vasoconstriction as occurs in, chronic hypertension or aortic stenosis.

Eccentric left ventricular hypertrophy is induced by an increased filling pressure of the left ventricle, otherwise known as diastolic overload, which represents the underlying mechanism for volumetric or diastolic overload in patients with regurgitant valve lesions such as aortic or mitral regurgitation as well as in the case of dilated cardiomyopathy. In patients with coronary artery disease, these mechanisms can play a role in an attempt to compensate for ischemic or infarcted myocardial tissue. This type of sustained increase in wall stress along with cytokine and neuro-activation stimulates the development of myocardial hypertrophy or increasing muscle thickness with the deposition of the extracellular matrix. This increased mass of muscle fibers or wall thickness serves initially as a compensatory mechanism that helps to maintain contractile forces and counteracts the increased ventricular wall stress. The benefits of increased wall thickness to compensate for elevated wall stress are offset by a significant increase in the degree of stiffness of the hypertrophied walls associated with a significant increase in diastolic ventricular pressures, which are subsequently transmitted back into the left atrium as well as the pulmonary vasculature.

One key pathophysiologic component in LVH is the concomitant development of myocardial fibrosis. Initially, fibrosis is clinically manifested by diastolic dysfunction, but systolic dysfunction will also develop with progressive disease.

Myocardial fibrosis appears to be pathophysiologically linked to the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS). Evidence has been established that angiotensin II produces a profibrotic effect in the myocardial tissue of hypertensive patients. This explains why angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) are among the most potent agents in the treatment of hypertension, especially from the standpoint of morbidity and mortality. LVH has been shown to be a consistent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity as well as mortality in hypertensive patients.[3] Certain antihypertensive therapies that induce regression of LVH decrease rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and enhance survival, regardless of the degree of blood pressure reduction. The clinical importance is two-fold: 1) recognizing that LVH can be a modifiable risk factor and 2) that management choices are significantly more complex than just controlling the blood pressure.[4]

Genomics may also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of LVH. Mutated genes that encode proteins of the sarcomere have a direct etiologic relationship in patients who present with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Also, there seems to be a genetic predisposition evidenced by the fact that some mildly hypertensive patients develop LVH while others do not.[5]

Histopathology

A heart undergoing hypertrophy usually exhibits changes in architecture as well as histology depending on the cause and stage of hypertrophy. Various histologic changes have been demonstrated and include volume fraction of fibrous tissue, degree of myocyte diameter, as well as ultrastructural changes in mitochondria. It has also been postulated that the cardiac renin-angiotensin system, as well as angiotensin-converting enzyme function, may be important factors in the hypertrophic response. The fact that myocardial hypertrophy may develop independently of hypertension suggests that angiotensin II may play a role as it induces myocardial fibrosis as well. Recent studies where regression analysis was performed showed that plasma angiotensin II, ACE, and renin levels correlated with left ventricular mass independent of blood pressure.[3] Regression analysis also showed that the most important element was angiotensin II levels, which appears closely related in part to stimulation of myocardial fibrosis.

Other factors that have been implicated in the development of myocardial hypertrophy include endothelin, heterotrimeric G proteins, as well as the role of cardiac sodium-potassium pumps. There may also be a pro-LVH genotype that has been demonstrated. Finally, other factors that may have a role in the degree of LVH include concomitant coronary disease or valvular heart disease as well as inflammatory cytokines calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II signal transducer and activator of transcription-3.[6]

Toxicokinetics

When the heart is exposed to long periods of increased workload, it undergoes hypertrophic enlargement secondary to the increased demand. Various cardiovascular pathologies such as myocardial infarction, stimulant drug abuse, or obesity have been shown to induce cardiac cell hypertrophy, which may lead to heart failure. Various signaling modulators in the cardiovascular system have been demonstrated to regulate cardiac mass, including an influence on gene expression, apoptosis, cytokines, as well as stimulation of growth factor. Recent studies suggest that pathological hypertrophy can be reversed or prevented altogether. Other molecular mechanisms potentially causing cardiac hypertrophy include the aberrant re-expression of a fetal gene program. A variety of molecular pathways that potentially induce a coordinated control of the program that induces hypertrophy include the following: natriuretic peptides, adrenergic nervous system, adhesion, and cytoskeletal proteins, IL-6 cytokines, MEK-ERK1/2 signaling, histone acetylation, calcium-mediated modulation and the role of microRNAs in controlling the cardiac hypertrophic response. At a cellular level, cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is characterized by an increase of cell size, up-regulation of protein synthesis, and intensified organization of the sarcomere. Mechanical stress induces a hypertrophic response downstream of mechanosensitive molecular structures. The sarcomeric Z-disc and its proteins seem to drive mechanical stress-induced signal transduction or mechanotransduction. An example of mechanosensitive molecules includes a family of Z-disc-specific proteins, calsarcins, or myozenins. Calsarcins have been demonstrated to attach the cardiac skeletal apparatus to signaling molecules that directly impact gene expression by binding to the Z-disc myofilament anchor proteins, a-actinin, and telethonin, and then attaching them to calcineurin, a calcium-dependent phosphatase demonstrated to induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by transcriptional pathways downstream.[7]

History and Physical

Patients may have had long-standing hypertension without even knowing it. After hypertension is confirmed on at least three different occasions based on the average of two or more readings taken at each of the subsequent visits, clinicians should assess the patient for evidence of end-organ damage involving the heart, brain, eyes, and kidneys. Most cases of hypertension are essential hypertension. However, secondary causes, such as renal artery stenosis, coarctation of the aorta, and/or metabolic disorder such as pheochromocytoma or hyperaldosteronism, hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, as well as hyperthyroidism must be excluded. Sleep apnea syndrome has been linked to both pulmonary hypertension as well as systemic hypertension. Also, according to the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (JNC 7) guidelines, the patient should be assessed for cardiovascular risk factors other than hypertension, including metabolic syndrome, tobacco use, increased LDL-cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, obesity, family history of premature cardiovascular death, lack of exercise, and microalbuminuria. Social history should include the patient's use of over-the-counter medications since herbal medications such as licorice or ephedrine could cause left ventricular hypertrophy. The patient should also be asked about the use of oral contraceptives, excess alcohol intake, as well as the use of cardiac stimulants such as cocaine or amphetamines.

A funduscopic exam in long-standing hypertension reveals hypertensive retinopathy. These signs usually develop later in the course of the disease. The exam will often show arteriovenous nicking, arteriolar constriction, cotton, wool spots, flame-shaped hemorrhages, yellow hard exudates, as well as edema of the optic disc. Signs and symptoms of hypertensive heart disease depend most commonly on the severity and duration as well as type of hypertrophy. Once left ventricular hypertrophy is established, the patient commonly manifests an S4 gallop, which reflects diastolic dysfunction or diminished left ventricular compliance, which can lead to initially diastolic heart failure and, ultimately, systolic heart failure. Another manifestation of left ventricular hypertrophy includes a sustained apical impulse shifted to the left or towards the axilla, reflecting hypertrophied heart muscle. Patients who have hypertensive heart disease secondary to coarctation of the aorta will manifest a systolic ejection murmur, radiating to the back as well as diminished or virtually absent lower extremity peripheral pulses.[8]

Hemodynamic valvular lesions can lead to hypertrophy with signs of concentric or eccentric remodeling of the left ventricle. Although initially compensatory, a thicker myocardial wall that reduces left ventricular radial and circumferential wall stress will benefit the systolic function of the left ventricle. With aortic stenosis, there would be a harsh systolic ejection murmur peeking in mid-to-late systole radiating from the aortic area into the carotid arteries associated with pulsus parvus et tardus. Patients with aortic insufficiency, especially if long-standing, will manifest a diastolic blowing murmur, heard over the aortic area radiating down the left lower sternal border. Other clinical signs of severe chronic aortic insufficiency are often the result of an increased or widened pulse pressure because the incompetent aortic valve allows a more significant fall in the diastolic pressure when compared to normal. Bounding or pistol-shot pulses may also be present. Because of the volumetric alterations of the left ventricle resulting hypertrophy is eccentric. This type of eccentric hypertrophy is also seen in patients with chronic mitral regurgitation.

Evaluation

Electrocardiography (ECG) is the least expensive and most readily available test for the diagnosis of LVH. While its specificity is relatively high, its low sensitivity makes the clinical utility somewhat limited. Various criteria for LVH by ECG have been suggested over the years. Most criteria utilize the voltage in one or more leads, QRS duration, secondary ST-T wave abnormalities, or left atrial abnormalities. The best recognized established ECG criteria are the Cornell voltage, the Cornell product, the Sokolow-Lyon index, as well as the Estes-Romhilt point scoring system.

ECG is relatively insensitive in diagnosing LVH because it relies on the measurement of the electrical activity of the heart by electrodes placed on the surface of the skin to predict the left ventricular mass. The intracardiac electrical signal is problematic to measure in this way because the measurements are impacted by all elements that lie between the heart muscle and the ECG electrodes, specifically fat, fluid, and air. Because of the variations in these elements, ECG underdiagnoses LVH in patients with pleural effusions, pericardial effusions, anasarca, obesity as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Also, LVH diagnosed by ECG is strongly impacted by both age and ethnicity. While electrocardiography is not sensitive and cannot be used to definitively exclude the diagnosis of LVH, it still plays a diagnostic and management role. In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study, LVH regression (diagnosed by ECG utilizing the Sokolow-Lyon index or the Cornell product criteria) in response to losartan (Cozaar) improved clinical cardiovascular outcomes independent of blood pressure response.

An echocardiogram is the test of choice in establishing the diagnosis of LVH. Its sensitivity is significantly higher than ECG, and the test can also diagnose other abnormalities such as left ventricular dysfunction (both systolic as well as diastolic) and valvular heart disease. Cardiac ultrasound utilizes transthoracic or transesophageal positioning of the transducer to measure the left ventricular end-diastolic diameter, posterior wall thickness, and interventricular septum thickness. From these measurements and the patient’s height and weight, the LV mass index can be determined. According to the American Society of Echocardiography and/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging, LVH is defined as an increased left ventricular mass index (LVMI) to greater than 95 g/m in women and increased LVMI to greater than 115 g/m in men. Despite the advantages of echocardiography and Doppler analysis, an important consideration in using this tool as a screening test in all hypertensive patients is its significant cost when compared to ECG.

In terms of specific testing for LVH, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is now considered the gold standard as it is even more precise and reproducible than cardiac ultrasound. It can accurately estimate LV mass and determines if other structural cardiac abnormalities are present. The widespread use of MRI is severely restricted in clinical practice due to its cost, logistics, and limited availability. While it may never be useful in screening for LVH, it has a significant role in clinical research and in the assessment of cardiovascular anatomy in certain clinical situations.[9]

Treatment / Management

The management of LVH depends on the etiology. Treatment involves lifestyle changes, and depending upon the cause, may include medication, surgery, and an implantable device for the prevention of sudden cardiac death. LVH treatment should be aggressive because patients with LVH are at the highest risk for cardiovascular events and mortality. The goal is to regress LVH and prevent LV dysfunction and progression to heart failure. Two-third of the patients with LVH are hypertensive. Blood pressure (BP) control is essential for preventing further deterioration and complications. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), long-acting calcium channel blockers (CCBs), or thiazide/thiazide-like diuretics are the recommended antihypertensives for LVH. The antihypertensive therapy benefits the patient by reducing BP and may regress LVH independent of BP reduction, leading to reduced adverse cardiovascular events and mortality.[10]

The other common cause of LVH is aortic stenosis. Patients with aortic stenosis usually have a 10 to 20 years asymptomatic latent period, during which increasing LV outflow obstruction and pressure load on the myocardium, may gradually change the composition of myocardial extracellular matrix leading to LVH. Usually, aortic valve replacement (AVR) is recommended in symptomatic patients, but if the echocardiographic findings show rapidly progressing aortic stenosis with LV dysfunction, AVR would be recommended in asymptomatic patients to improve LV function and reduce mortality.

Athletic heart with physiological LVH does not require treatment. Discontinuation of training for a few months (3 to 6 months) is usually needed to regress LVH. LVH regression is monitored for a few months to distinguish it from cardiomyopathy. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy patients, beta-blockers and CCBs are used to reduce the heart rate and decrease myocardial contractility so that diastolic filling can be prolonged. If symptoms persist despite medical therapy, surgical myomectomy, or septal ablation is indicated. In these specific cases, drugs like diuretics, ACEI, or ARBs are avoided because they decrease the preload and worsen the ventricular function.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

A most challenging clinical dilemma attempts to differentiate between physiological left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) (athlete's heart) and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), which is recognized as the most common cause of non-traumatic exercise-induced sudden cardiac death in young athletes (<35 years old). Detailed echocardiography assessment of left ventricle structure and left ventricle function helps in making the diagnosis.[11]

As outlined above, the differential diagnosis to consider in patients with evidence of LVH includes:

- Essential hypertension

- Renal artery stenosis

- Athletic heart with physiological LVH

- Aortic valvar stenosis

- Coarctation of the aorta

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy without or with outflow tract obstruction (HOCM)

- Subaortic stenosis (left ventricular outflow tract obstruction by muscle or membrane)

- Aortic regurgitation

- Mitral regurgitation

- Dilated cardiomyopathy

- Ventricular septal defect

- Infiltrative cardiac processes (e.g., Amyloidosis, Fabry disease, Danon disease)

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

In the Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study, LVH regression (diagnosed by ECG utilizing the Sokolow-Lyon index or the Cornell product criteria) in response to losartan improved clinical cardiovascular outcomes independent of blood pressure response. LVH is a consequence of the complex interaction of genomic factors, environment as well as lifestyle. LVH is reflective of end-organ dysfunction in HTN and other diseases such as valvular heart disease. A number of studies have demonstrated that LVH in and of itself is a significant independent risk factor for increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and, therefore, a major public health burden, especially in light of an aging population. There is also accumulating evidence that targeting LVH regression is not only feasible but necessary in order to achieve improved clinical outcomes. Therefore, in treating hypertension as well as valvular disease, LVH regression should be considered an important surrogate endpoint. Among the various drugs used in the treatment of hypertension, those that target the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), particularly angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is), appear to have unique class actions that decrease left ventricular hypertrophy by reducing LV mass independent of blood pressure control. Also, besides treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors/or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB’s), calcium channel blockers and beta-blockers have also been shown to reduce LV mass. This is associated with reduced arrhythmias, mortality, and risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD). It is yet to be definitively proven whether this decrease in LV mass produces significant improvement in clinical outcomes. This would indicate that in the future, the new target in treating left ventricular hypertrophy will require an understanding of an individual’s genomic makeup through new study designs in personalized medicine as well as advances in genetic technologies in order to identify the overall impact on the regression of LVH.

Prognosis

The presence of LVH forecasts an increased risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, even after adjustment for major cardiovascular risk factors such as age, smoking, obesity dyslipidemia, blood pressure, and diabetes. This means that LVH is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Once LVH is developed, it puts the patient at significant risk of developing myocardial ischemia and infarction, heart failure, dysrhythmias, or even sudden death. The risk of cardiovascular disease and adverse major cardiac events increases with increasing LVM and decreases with the regression of LVH.

Complications

Since continuous pressure or volume overload may remain in a compensatory phase, patients with LVH remain asymptomatic for a few years. But as the disease progresses, it will lead to the development of systolic or diastolic dysfunction and end-stage heart failure. Increased myocardial oxygen demand eccentric hypertrophy may result in angina or ischemic symptoms. Also, LVH predisposes to arrhythmias because hypertrophied cardiac muscle disrupts normal conduction. This predisposes to atrial fibrillation that may lead to ischemic stroke.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated about the relevance of lifestyle modifications for improving blood pressure control. This includes cessation of smoking, avoidance of sedentary lifestyle and maintaining an active lifestyle (exercise at least three times a week), reduced salt intake (under 2 g/day), and avoidance of alcohol. The patient should be educated about the risks of uncontrolled blood pressure and the benefits of home monitoring and keeping daily logs of their blood pressure measurements. Because hypertension is the most common and easily modifiable cause of LVH, proper management is important. It will help prevent deterioration and may result in the regression of LVH. Along with compliance with lifestyle modification, pharmacologic compliance is also important to prevent associated CV morbidity and mortality.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The association of LVH with increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality demands aggressive treatment, but the initial asymptomatic nature of LVH may lead to delayed treatment. This fact highlights the need for early detection and treatment and the importance of a collaborative interprofessional team consisting of community health workers, dietitians, nurse practitioners, primary care providers, pharmacists, cardiologists, and an internist. Depending on the cause of LVH and associated complications, the team may involve a cardiac surgeon and an electrophysiologist. The role of community health workers is important in creating awareness in communities about hypertension and LVH. Increasing public awareness about the prevention of hypertension with lifestyle modifications such as weight loss, physical activity, low salt intake, and cessation of smoking and alcohol intake [Level 1] can greatly improve outcomes. Healthcare providers should encourage regular monitoring of blood pressure in the community setting, compliance with lifestyle modifications, and pharmacological treatment.

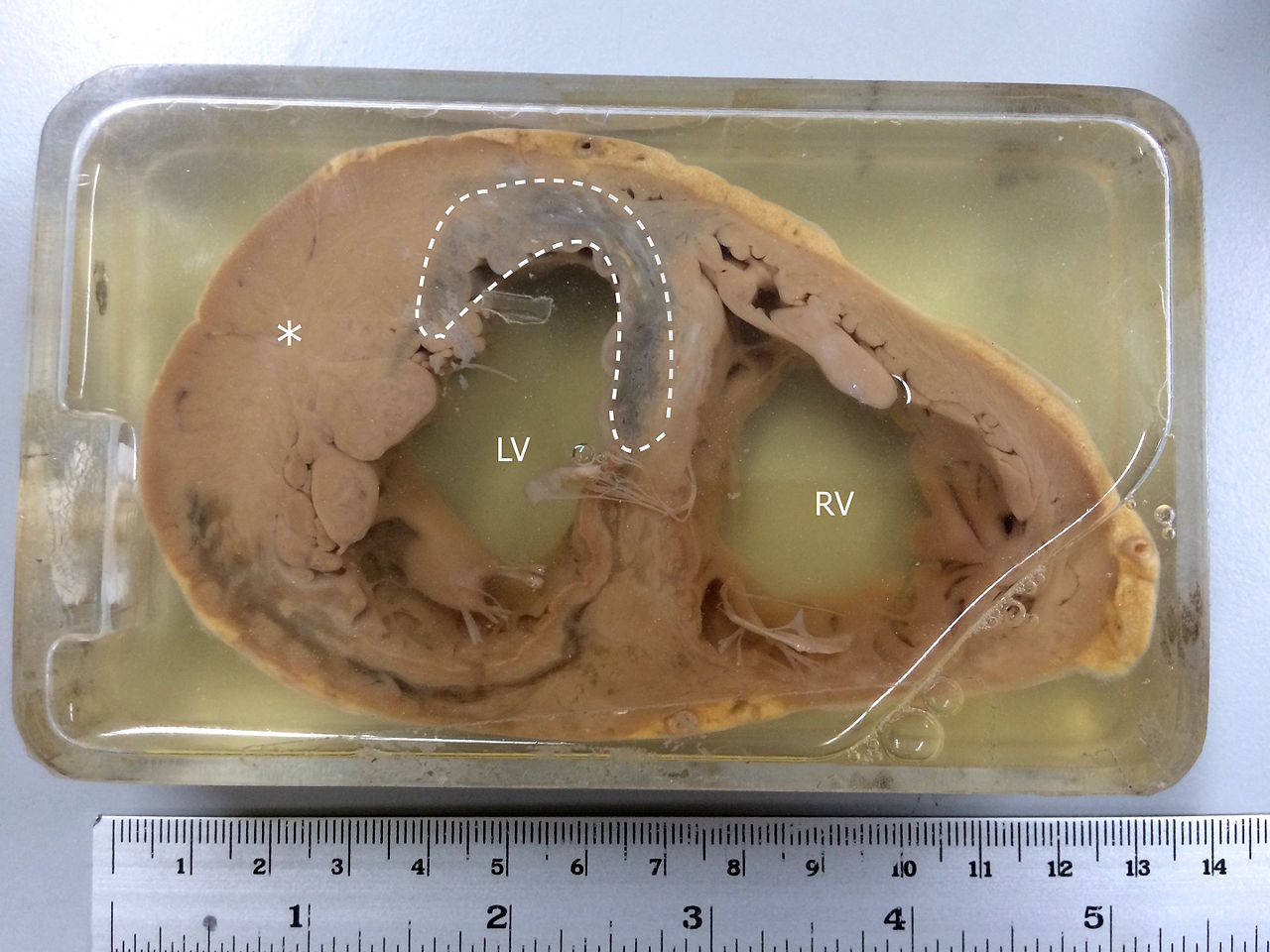

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cuspidi C, Sala C, Negri F, Mancia G, Morganti A, Italian Society of Hypertension. Prevalence of left-ventricular hypertrophy in hypertension: an updated review of echocardiographic studies. Journal of human hypertension. 2012 Jun:26(6):343-9. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2011.104. Epub 2011 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 22113443]

Marketou ME, Parthenakis F, Vardas PE. Pathological Left Ventricular Hypertrophy and Stem Cells: Current Evidence and New Perspectives. Stem cells international. 2016:2016():5720758. doi: 10.1155/2016/5720758. Epub 2015 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 26798360]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJia G, Aroor AR, Hill MA, Sowers JR. Role of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Activation in Promoting Cardiovascular Fibrosis and Stiffness. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex. : 1979). 2018 Sep:72(3):537-548. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29987104]

Sciarretta S, Paneni F, Palano F, Chin D, Tocci G, Rubattu S, Volpe M. Role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and inflammatory processes in the development and progression of diastolic dysfunction. Clinical science (London, England : 1979). 2009 Mar:116(6):467-77. doi: 10.1042/CS20080390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19200056]

Marian AJ, Braunwald E. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Genetics, Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Circulation research. 2017 Sep 15:121(7):749-770. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28912181]

Maillet M, van Berlo JH, Molkentin JD. Molecular basis of physiological heart growth: fundamental concepts and new players. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology. 2013 Jan:14(1):38-48. doi: 10.1038/nrm3495. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23258295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSamak M, Fatullayev J, Sabashnikov A, Zeriouh M, Schmack B, Farag M, Popov AF, Dohmen PM, Choi YH, Wahlers T, Weymann A. Cardiac Hypertrophy: An Introduction to Molecular and Cellular Basis. Medical science monitor basic research. 2016 Jul 23:22():75-9. doi: 10.12659/MSMBR.900437. Epub 2016 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 27450399]

Agabiti-Rosei E,Muiesan ML,Salvetti M, Evaluation of subclinical target organ damage for risk assessment and treatment in the hypertensive patients: left ventricular hypertrophy. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006 Apr [PubMed PMID: 16565230]

Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE. Left ventricular hypertrophy and clinical outcomes in hypertensive patients. American journal of hypertension. 2008 May:21(5):500-8. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2008.16. Epub 2008 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 18437140]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWilliams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak A, Kahan T, Mahfoud F, Redon J, Ruilope L, Zanchetti A, Kerins M, Kjeldsen SE, Kreutz R, Laurent S, Lip GYH, McManus R, Narkiewicz K, Ruschitzka F, Schmieder RE, Shlyakhto E, Tsioufis C, Aboyans V, Desormais I, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European heart journal. 2018 Sep 1:39(33):3021-3104. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30165516]

Malhotra A, Sharma S. Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy in Athletes. European cardiology. 2017 Dec:12(2):80-82. doi: 10.15420/ecr.2017:12:1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30416558]