Introduction

The teeth are multifunctional appendages that essential in basic human functions, like eating and speech. Teeth are composed of multiple unique tissues with varying density and hardness that allows them to tolerate the significant forces and wear of mastication. They are attached to the maxilla (upper jaw) and the mandible (lower jaw) of the mouth. Humans have four different types of teeth that each have a specific function, which is classified by structure and location. Also, humans have two generations of teeth throughout a lifetime: 20 primary teeth and 32 permanent teeth.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Structure

Teeth are calcified structures found in the oral cavity embedded to the upper jaw (maxilla) and lower jaw (mandible). Human teeth are heterodont and characterized by four tooth classes: incisors, canines, premolars, and molars. Human teeth are also diphyodont because there are two generations of teeth during a lifespan: 20 deciduous (primary) teeth and 32 permanent teeth. The primary dentition consists of the two types of incisors - central and lateral, canines, and two types of molars - first and second. The primary incisors, canines, and molars get replaced by the successional permanent incisors, canines, and premolars. Permanent dentition also consists of the additional teeth that are three types of molars - first, second, and third. The process fo identifying teeth uses the Universal National System. In the maxilla, permanent adult teeth are numbered 1 through 16 from right to left, and primary teeth are labeled with letters A through J from right to left. In the mandible, permanent adult teeth are numbered 17 through 32 from left to right, and primary teeth are labeled with letters K through T from left to right.[2][3]

The anatomy of a tooth divides into two main sections: the crown and the root. The crown of the tooth is what is visible in the oral cavity, and the root of the tooth is embedded into the bony ridge of the upper and lower jaws called the alveolar process via attachment to the periodontal ligament. The gingiva covers the border of the alveolar process that is adjacent to the teeth. The cementoenamel junction is the anatomical boundary between the enamel-covered crown and cementum covered root. Dentin makes up the core of the entire tooth that surrounds the pulp, which contains the neurovascular structures. The apical foramen at the root apex is where the neurovascular structures enter the tooth and travel up the root canal to the expanded pulp chamber of the crown. The roots of the tooth vary depending on the type of tooth. The molars typically have three roots: a lingual root on the lingual aspect and a mesiobuccal root and distobuccal root on the buccal aspect. The crown of the tooth has five surfaces. The surface facing the lip or cheek is called the facial surface for incisors and canines and buccal surfaces for premolars and molars. The surface facing the inside of the mouth is referred to as the palatal surface in the maxilla and the lingual surface in the mandible. The surfaces referring to the boundaries of adjacent teeth are called mesial and distal. Mesial refers to the surface closer to the midline of the face, and distal refers to the surface away from the midline of the face. The biting surface is called the occlusal surface.[4][1][5]

The structure of a tooth is made up of specialized tissues that allow it to survive the forces of mastication while maintaining retention in the oral cavity. Enamel is the hardest tissue in the body and serves as a protective outer covering for the tooth crown. Enamel consists of 96% mineral by weight primarily of a complex, highly organized structure of carbonate-substituted hydroxyapatite mineral arranged in interlocking prisms giving it its characteristic strength. Dentin is the most plentiful tissue in a tooth, and it is mostly responsible for the size and shape of a tooth. Dentin consists of 60% mineral by weight and 20% organic component arranged in a complex organization of tubules filled with fluid. Dentin’s structure can flex and absorb force allowing it to function as a substructure for enamel. The pulp is a specialized tissue at the core of the tooth that contains blood vessels, nerves, odontoblasts, fibroblasts, and an extracellular matrix providing the tooth with neurosensory function and reparative potential. Cementum is the specialized hard tissue covering the tooth root that connects to the periodontal ligament attached to the alveolar bone; this works as an attachment system to hold the tooth in place under physiological loads of mastication.[4][5][1]

Function

The basic function of teeth mastication of food to create a swallowable food bolus. Teeth also play a crucial role in speech and facial aesthetics. Teeth provide a masticatory system that functions in the incising, tearing and grinding of food. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers the number of teeth to be a key indicator of oral health status. Retention of function, aesthetics, and natural dentition of at least 20 teeth with nine to ten occluding pairs (including anterior teeth) is associated with adequate masticatory efficiency and ability. Teeth also play a role in satisfaction and facial aesthetics. Loss of anterior teeth has shown to impair aesthetics and satisfaction for most people. Although complete dentition is not necessary to satisfy oral function needs, a low functional level may lead to malnutrition and compromised physiological and psychological health.[1][2][6]

Embryology

The basis of development of human dentition begins at the sixth week of embryological development when the primary epithelial band, a thick band of epithelium, arises from the proliferation of the oral ectoderm. The primary epithelial band develops into the vestibular and dental laminae. The vestibular lamina forms the free space between the cheek and the alveolar process. The dental lamina is a horseshoe-shaped ridge of thickened epithelium overlying the jaws that gives rise to human dentition.[3][2]

Teeth form via the process of odontogenesis. Human dentition is diphyodont, meaning there are two generations of functional teeth during life: deciduous teeth and permanent teeth. Humans have 20 deciduous, or temporary baby, teeth that get replaced by 32 succedaneous, or permanent adult, teeth. Around the sixth- to eight-week of embryonic development, the odontogenesis of deciduous teeth begins. In the twentieth week of embryonic development, the odontogenesis of permanent teeth begins. Every tooth develops from the ectoderm and the ectomesenchyme. The enamel arises from the ectoderm. The dentin, cementum, periodontal ligament, and pulp arise from the ectomesenchyme, which comprises the transformation of neural crest cells into developing maxillary and mandibular arches.[3][2]

Tooth formation initiates via the localized thickening of dental epithelium invaginating into the underlying mesenchyme to form the dental lamina. This process forms ten placodes, or focal thickenings of oral epithelium, each on the mandibular and the maxillary arches. The placodes develop into tooth buds, which eventually develop into teeth. During deciduous teeth development, teeth form starting from the anterior part of the maxilla and mandible and continue posteriorly. Given human dentition is heterodont, meaning there are four different tooth classes, different teeth erupt at different times, but they follow the same pattern of odontogenesis. Lingual to the deciduous teeth are tooth buds of permanent teeth positioned in a horseshoe-shaped arch. Every tooth bud, with the exceptions of the second and third permanent molars, are present and have started development prior to birth. Most of the activity of the dental lamina occurs over five years, but the activity of the dental lamina near the third molars continues until about 15 years of age.[3][2][7]

The tooth bud acquires a cap shape as it grows via the invagination of the mesenchyme. This complex of oral epithelium and mesenchyme is called the tooth germ. The tooth bud’s ectodermal cells form the enamel organ, containing the outer enamel epithelium, the stellate reticulum, and the inner enamel epithelium. The condensed mesenchyme cells lining the inner enamel epithelium layer is called the dental papilla. The dental papilla later forms the dental pulp tissue and odontoblasts. The other mesenchyme encompasses the enamel organ and the dental papilla to establish the dental follicle, a fibrous sac that supports the tooth germ and will differentiate into the supporting structures of the teeth: the periodontal ligament, cementum, and alveolar bone. Cell condensation occurs in the central region of the inner enamel epithelium forming the enamel knot, which is a signaling center for tooth development and is integral in the cusp formation of the crowns of the teeth.[3][7]

The tooth bud transforms into the shape of a bell when the tooth germ becomes an independent tissue due to the disappearance of the connection between the enamel organ and oral epithelium. The dental papilla cells that are attached to the inner epithelial cells at the basement membrane begin to differentiate into odontoblasts at the future cusp area. The inner epithelial cells that are attached to the odontoblasts differentiate into ameloblasts. The odontoblastic process forms when the odontoblasts differentiate and move towards the dental papillae while staying attached to the basement membrane of the dental lamina, which disappears when dentin mineralization begins. Later in the bell stage, mineral deposition begins when the odontoblasts produce dentin initiating the ameloblasts to produce enamel. This change begins at the cusp of the tooth and proceeds in the direction of the apex, or root, of the tooth. When the inner and outer enamel epithelium joins to form the cervical loop, the dental papillae become enclosed by the epithelial root sheath and induces root formation. As dentin production continues to increase, the pulp cavity fills and narrows to form the root canal. Enamel production only occurs in teeth before the eruption, while dentin can be produced throughout life.[3][7]

Tooth eruption is the process of a developing tooth penetrating oral soft tissue to enter the oral cavity. The eruption occurs when the mineralization and formation of the crown are mostly complete but before the full formation of the roots. When erupting teeth are no longer impeded by oral soft tissue, they erupt rapidly and are fully erupted within six months as long as there is space for them. Usually, the first primary teeth to erupt are the mandibular central incisors between 6 to 10 months of age. Next, the primary maxillary central incisors and lateral incisors erupt between 8 to 13 months of age. The primary mandibular lateral incisors erupt between 10 to 16 months of age. The primary canines erupt between 16 to 23 months of age. The primary first molars erupt between 13 to 19 months of age. The primary second molars erupt between 23 to 33 months of age. The primary central incisors shed between 6 to 7 years of age and are succeeded by the eruption of permanent mandibular central incisors at 6 to 7 years of age and maxillary central incisors at 7 to 8 years of age. The primary lateral incisors shed between 7 to 8 years of age and are succeeded by the eruption of permanent mandibular lateral incisors between 7 to 8 years of age and maxillary lateral incisors between 8 to 9 years of age. The primary canines shed between 9 to 12 years of age and are succeeded by the eruption of permanent mandibular canines between 9 to 10 years of age and maxillary canines between 11 to 12 years of age. The primary first molars shed between 9 to 11 years of age and are succeeded by the eruption of permanent mandibular first premolars between 10 to 12 years of age and maxillary first premolars between 10 to 11 years of age. The primary second molars shed between 10 to 12 years of age and are succeeded by the eruption of permanent second premolars between 10 to 12 years of age. The permanent first molars erupt between 6 to 7 years of age. The permanent second molars erupt between 11 to 13 years of age. The permanent third molars erupt between 17 to 21 years of age if there is room for them.[1][8][3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood Supply

The maxillary artery, which is the terminal branch of the external carotid artery, supplies blood to both the maxillary and mandibular teeth—the maxillary artery branches into the inferior alveolar artery, which supplies blood to the mandibular arch. The inferior alveolar artery enters the mandibular foramen and proceeds along the inferior alveolar canal, supplying nutrient branches to mandibular molars. At the mental foramen, the inferior alveolar artery branches into the mental and incisive arteries. The incisive artery travels along the incisive canal to supply nutrients to the mandibular premolars, canines, and incisor teeth and exits the mandible in the midline through the lingual foramen to anastomose with the lingual artery of the tongue. The inferior alveolar vein is responsible for collecting blood throughout the mandible and exits the mandibular foramen to drain into the pterygoid venous plexus.[5][9]

The maxillary artery supplies blood to the maxillary arch with the posterior superior alveolar artery, the middle superior alveolar artery, and the anterior superior alveolar artery. The posterior superior alveolar artery arises from the maxillary artery before entering the pterygopalatine fossa and supplies blood to the maxillary sinus, molars, and premolars. The infraorbital artery arises directly from the maxillary artery and gives the middle superior alveolar artery and anterior superior alveolar artery. The middle superior alveolar artery supplies blood to the maxillary sinus and premolars. The anterior superior alveolar artery supplies the maxillary sinus and anterior maxillary teeth - canines and incisors. The posterior, middle, and anterior superior alveolar arteries collect blood from the maxilla and drain into the pterygoid venous plexus.[3][10]

Lymphatics

There are few and controversial data regarding the existence of a lymphatic drainage system in the human dental pulp. Based on the data of Geri et al. obtained in a morphological study, their results suggest that human dental pulp does not contain lymphatic vessels under normal conditions. However, lymphatic vessels may appear following inflammation.[11]

Nerves

The nerves that innervate teeth originate from the trigeminal nerve, which is the largest cranial nerve. Distal to the trigeminal ganglion, the trigeminal nerve divides into three branches: the ophthalmic nerve, the maxillary nerve, and the mandibular nerve. The maxillary and mandibular nerves give off branches that innervate the teeth in addition to surrounding gingiva, other soft tissues, and muscle.[12]

The maxillary nerve is the second division of the trigeminal nerve. It carries sensory fibers to the maxillary teeth, the skin overlying the maxilla, upper lip, palate, and the maxillary sinuses. The maxillary nerve divides into sensory branches at the pterygopalatine fossa: the meningeal branches, the superior alveolar nerves, the infraorbital nerve, and the zygomatic nerve. The other branches of the maxillary nerve that originate from the pterygopalatine ganglion are the nasopalatine and palatine nerves. The infraorbital nerve directly extends from the maxillary nerve and gives the superior alveolar nerves for the innervation of the maxillary teeth. The infraorbital nerve gives the anterior superior alveolar nerve and the middle superior alveolar nerve. The maxillary nerve gives off the posterior superior alveolar nerve is given off at the pterygopalatine fossa. The posterior superior alveolar nerve, the middle superior alveolar nerve, and the anterior superior alveolar nerve form the superior dental plexus, which innervates the teeth of the upper jaw.[12]

The posterior superior alveolar nerve forms the posterior portion of the superior dental plexus and innervates the maxillary molar teeth, the surrounding gingiva, the mucosa of the cheek, and the membrane of the maxillary sinus. The middle superior alveolar nerve forms the middle portion of the superior dental plexus and innervates the maxillary premolar teeth and lateral wall of the maxillary sinus. The anterior superior alveolar nerve forms the anterior portion of the superior dental plexus and innervates the anterior maxillary teeth - canines and incisors, as well as the anterior maxillary sinus. The greater palatine nerve, the anterior branch of the palatine nerve, innervates the posterior hard palate and can give off additional branches to the maxillary molars and premolars. The nasopalatine nerve innervates the palate and palatal gingiva adjacent to the maxillary canine teeth and can give off other branches to the maxillary incisor teeth.[12][5]

The mandibular nerve is the third division of the trigeminal nerve and carries sensory fibers to the mandibular teeth and motor fibers to several mastication muscles. The inferior alveolar nerve is the largest branch of the mandibular nerve that innervates all of the mandibular teeth forming the inferior dental plexus. Before entering the mandibular foramen, the inferior alveolar nerve gives off the mylohyoid nerve supplying the mylohyoid and digastric muscles, and sometimes branches to the mandibular premolars, canines, and incisors. The inferior alveolar nerve enters through the mandibular foramen to the mandibular canal, supplying dental and interdental branches to the mandibular molars and premolars and then gives off two terminal branches at the level of the second premolar at the mental foramen: the mental nerve and the incisive nerve. The mental nerve is the larger of the two and innervates the skin of the chin and the mucosa and skin of the lower lip. The incisive nerve is the smaller branch that innervates the mandibular premolars, canines, and incisor teeth as well as their associated gingiva.[12][5]

Muscles

The four muscles of mastication are the temporalis, masseter, medial pterygoid, and lateral pterygoid muscles. These muscles receive motor innervation from the mandibular nerve branches. The masseter muscle functions to elevate and protract the mandible. The temporalis muscle functions to elevate and retract the mandible. The medial pterygoid functions to further assist the elevation and protrusion of the mandible, but can also facilitate side-to-side grinding. The temporalis, masseter, and medial pterygoid muscles work synergistically to close the jaw vertically during mastication. The lateral pterygoid muscle is thought to control jaw movement, but there is a limited understanding of its function. The lateral pterygoid has a superior head and an inferior head that are thought to have different functions. The inferior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle is thought to play a role in the opening, protrusion, and contralateral movements of the jaw. The superior head of the lateral pterygoid muscle is thought to play a role in the closing, retrusion, and ipsilateral movements of the jaw.[5][13][14]

Physiologic Variants

Teeth can have physiological variants in terms of number, size, and shape. Tooth anomalies in number size and shape happen during development. The number of teeth can be decreased with hypodontia, or the condition of congenital absence of teeth, and increased with hyperdontia, or the condition of the presence of supernumerary teeth. Tooth size alters with conditions like megadontia, the relative enlargement of teeth, and microdontia, the relative decrease in size of teeth. The shape of a tooth can vary when it has a Carabelli cusp, which is an additional, non-functioning, mini cusp found on the side of the tooth facing the inside of the mouth.[15]

The structures of teeth can have physiological variants as well. Given the vast amount of environmental influences or genetic mutations that can affect the development of enamel, the general population reports a high prevalence of enamel defects. Excessive exposure to fluoride can cause fluorosis, which in mild cases is characterized by a white, lacy appearance of the enamel and, in severe cases, can cause enamel to be hypomineralized with a characteristic brown color. Hereditary conditions like amelogenesis imperfecta can cause enamel defects in the absence of a systemic condition, which causes hypomineralization of the enamel. Dentin defects can happen with conditions like dentinogenesis imperfecta, which causes blue-gray to yellow-brown discoloration of the dentin, which shoes through the translucent enamel. It also can lead to enamel fractures due to the lack of support of poorly mineralized dentin.[1]

Physiological changes can happen in teeth due to normal aging. However, changes can happen at different rates due to multiple factors like lifestyle, environment, and genetics that influence them. The changes in the appearance of teeth that occur over time are due to the wearing of the enamel, chipping, fracture lines, staining, exposure of dentin, and reduction in the size of the pulp chamber and root canals. These changes result in teeth that are generally darker in color. Also, periodontal support can modestly decrease with age, which results in gum recession on the buccal surface of teeth. With regular care, dentition should function effectively throughout a lifetime.[16]

Surgical Considerations

When making a treatment plan for a questionable tooth, many factors come into play to decide whether the tooth should be treated and maintained, or extracted and replaced by an implant. From a periodontal standpoint, the prognosis of a tooth is determined by its amount of attachment loss and probing pocket depth. The progressive loss of periodontal attachment and increase in probe pocket depth are predictive of additional disease activity increases the likelihood of needing to be extracted. If the bone loss is too great with the periodontal loss, an implant would only be a possible replacement with successful bone volume augmentation. From a tooth structural standpoint, the prognosis of a tooth is determined by its amount of coronal structure remaining. A prosthetic crown can be placed on the tooth if there is sufficient structure remaining to retain the crown. Crown lengthening and extrusion can increase the amount of tooth structure for sufficient retention of a dental crown when appropriate.[17]

Clinical Significance

Dental caries is one of the most common chronic diseases that affect over 90% of people in the United States before age 30. Dental caries is a multifactorial disease involving an array of risk and protective factors that are dependent on personal, biological, behavioral, and environmental factors. Dental caries occur when a biofilm dysfunction causes long periods of low pH resulting in a net mineral loss of the tooth structure. Risk factors for dental caries include but are not limited to plaque buildup on teeth between brushings, medications that cause dry mouth, consuming drinks with sugar, constant snacking between meals, oral appliances, frequent tobacco use, acid reflux, diabetes, head and neck radiation therapy, bulimia, and Sjogren’s syndrome. Although some of these risk factors are modifiable with behavioral changes, others cannot, which is why clinicians must develop an individualized treatment plan for the patient.[18][19]

Dental caries present as a caries lesion on the tooth, which can present as a change in color or surface structure as a result of demineralization or a loss of enamel surface integrity, exposing underlying dentin becoming a cavitation. Initial caries development is characterized by demineralization, forming a non-cavitated lesion. The disease process can be stopped by re-establishing the homeostasis between remineralization and demineralization with the application of fluoride varnish. However, if the disease progresses, a cavitated lesion will form, which is characterized by a complete loss of enamel, exposing the underlying dentin. At that point, there is no biological mechanism to replace the loss of hard tissue, and treatment by placing a restoration may be required to stop the progression.[19]

Media

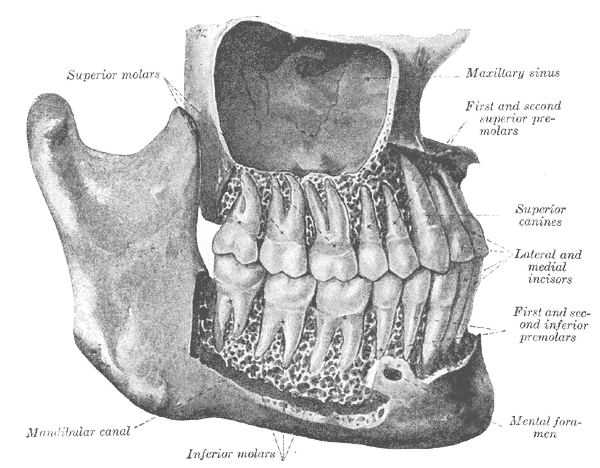

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Mouth, The Permanent Teeth. Viewed from the right, superior molars, mandibular canal, maxillary sinus, superior canines, lateral and medial incisors, and first and second inferior premolars.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Wright JT. Normal formation and development defects of the human dentition. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2000 Oct:47(5):975-1000 [PubMed PMID: 11059346]

Hovorakova M, Lesot H, Peterka M, Peterkova R. Early development of the human dentition revisited. Journal of anatomy. 2018 Aug:233(2):135-145. doi: 10.1111/joa.12825. Epub 2018 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 29745448]

Zohrabian VM, Poon CS, Abrahams JJ. Embryology and Anatomy of the Jaw and Dentition. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 2015 Oct:36(5):397-406. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2015.08.002. Epub 2015 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 26589693]

Li J, Parada C, Chai Y. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of tooth root development. Development (Cambridge, England). 2017 Feb 1:144(3):374-384. doi: 10.1242/dev.137216. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28143844]

Abrahams JJ, Frisoli JK, Dembner J. Anatomy of the jaw, dentition, and related regions. Seminars in ultrasound, CT, and MR. 1995 Dec:16(6):453-67 [PubMed PMID: 8747412]

Gotfredsen K, Walls AW. What dentition assures oral function? Clinical oral implants research. 2007 Jun:18 Suppl 3():34-45 [PubMed PMID: 17594368]

Kawashima N, Okiji T. Odontoblasts: Specialized hard-tissue-forming cells in the dentin-pulp complex. Congenital anomalies. 2016 Jul:56(4):144-53. doi: 10.1111/cga.12169. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27131345]

Holt R, Roberts G, Scully C. ABC of oral health. Oral health and disease. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2000 Jun 17:320(7250):1652-5 [PubMed PMID: 10856071]

Khoury JN, Mihailidis S, Ghabriel M, Townsend G. Applied anatomy of the pterygomandibular space: improving the success of inferior alveolar nerve blocks. Australian dental journal. 2011 Jun:56(2):112-21. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2011.01312.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21623801]

Matani JD, Kheur MG, Kheur SM, Jambhekar SS. The Anatomic Inter Relationship of the Neurovascular Structures Within the Inferior Alveolar Canal: A Cadaveric and Histological Study. Journal of maxillofacial and oral surgery. 2014 Dec:13(4):499-502. doi: 10.1007/s12663-013-0563-y. Epub 2013 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 26225018]

Gerli R, Secciani I, Sozio F, Rossi A, Weber E, Lorenzini G. Absence of lymphatic vessels in human dental pulp: a morphological study. European journal of oral sciences. 2010 Apr:118(2):110-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2010.00717.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20486999]

Rodella LF, Buffoli B, Labanca M, Rezzani R. A review of the mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies and their clinical relevance. Archives of oral biology. 2012 Apr:57(4):323-34. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2011.09.007. Epub 2011 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 21996489]

Butts R, Dunning J, Perreault T, Mettille J, Escaloni J. Pathoanatomical characteristics of temporomandibular dysfunction: Where do we stand? (Narrative review part 1). Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2017 Jul:21(3):534-540. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2017.05.017. Epub 2017 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 28750961]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurray GM, Bhutada M, Peck CC, Phanachet I, Sae-Lee D, Whittle T. The human lateral pterygoid muscle. Archives of oral biology. 2007 Apr:52(4):377-80 [PubMed PMID: 17141177]

Brook AH, Jernvall J, Smith RN, Hughes TE, Townsend GC. The dentition: the outcomes of morphogenesis leading to variations of tooth number, size and shape. Australian dental journal. 2014 Jun:59 Suppl 1():131-42. doi: 10.1111/adj.12160. Epub 2014 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 24646162]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLamster IB, Asadourian L, Del Carmen T, Friedman PK. The aging mouth: differentiating normal aging from disease. Periodontology 2000. 2016 Oct:72(1):96-107. doi: 10.1111/prd.12131. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27501493]

Zitzmann NU, Krastl G, Hecker H, Walter C, Waltimo T, Weiger R. Strategic considerations in treatment planning: deciding when to treat, extract, or replace a questionable tooth. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 2010 Aug:104(2):80-91. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60096-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20654764]

Kutsch VK. Dental caries: an updated medical model of risk assessment. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry. 2014 Apr:111(4):280-5. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.07.014. Epub 2013 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 24331852]

Young DA, Nový BB, Zeller GG, Hale R, Hart TC, Truelove EL, American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs, American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. The American Dental Association Caries Classification System for clinical practice: a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939). 2015 Feb:146(2):79-86. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2014.11.018. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25637205]