Introduction

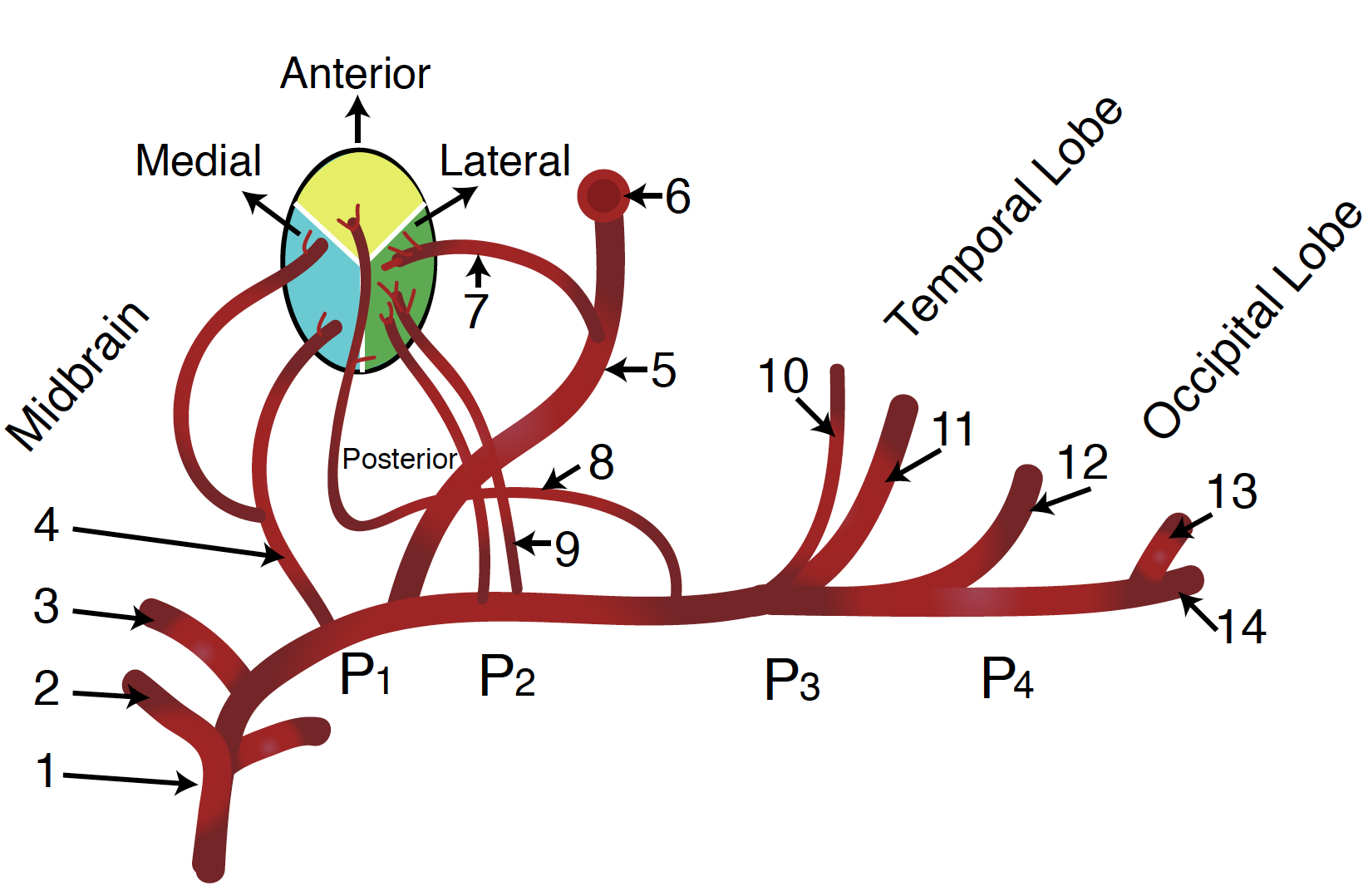

The brain vasculature provides the nutrients necessary for the well functioning of the central nervous system (CNS). Anatomical and angiographic studies considerably detail the topography of the arterial architecture and the related relationships. We review the arterial blood supply to the brain. Awareness of its normal anatomy and its common variations and anomalies are critical for the diagnostic and treatment of stroke and associated vascular disorders.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

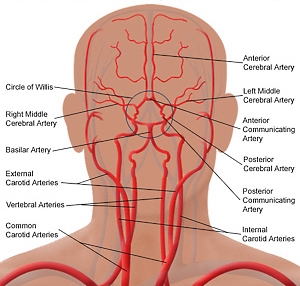

Four principal arteries supply the brain, namely one internal carotid artery (ICA) and one vertebral artery on each side. Classically the internal carotid arteries on both sides are referred to as the anterior circulation, while the vertebral-basilar arterial system composes the posterior circulation.[1] At the central cranial base, the anterior and posterior circulation connect to form an anastomotic ring called “circle/polygon of Willis.” The sides of the polygon of Willis are made of the anterior cerebral arteries (ACA), the posterior cerebral arteries (PCA), anterior communicant branch (Acom A) which bridge both ACA and the posterior communicant arteries (Pcom A) which links ICA and PCA on each hemibrain.[2]

Each ICA divides into 3 terminal branches: the ACA, the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and the anterior choroidal (artery ACh A). The PCAs are the terminal branches of the vertebrobasilar artery. Anatomists describe different segments of ACA, MCA, and PCA based on the bifurcating pattern.[3] Hence, ACA is subdivided in:

- A1: Horizontal or pre-communicating begins at the carotid bifurcation and ends at the level of ACom A.

- A2: Vertical or post communicating segment or pre callosal begins at Acom A and ends at the junction rostrum-genu of the corpus callosum.

- A3: Pre-callosal

- A4: Supra-callosal

- A5: Postero-callosal

A3 together with A4 and A5 are referred to as peri-callosal artery.

MCA is subdivided in:

- M1: Sphenoidal

- M2: Insular

- M3: Opercular

- M4: Cortical

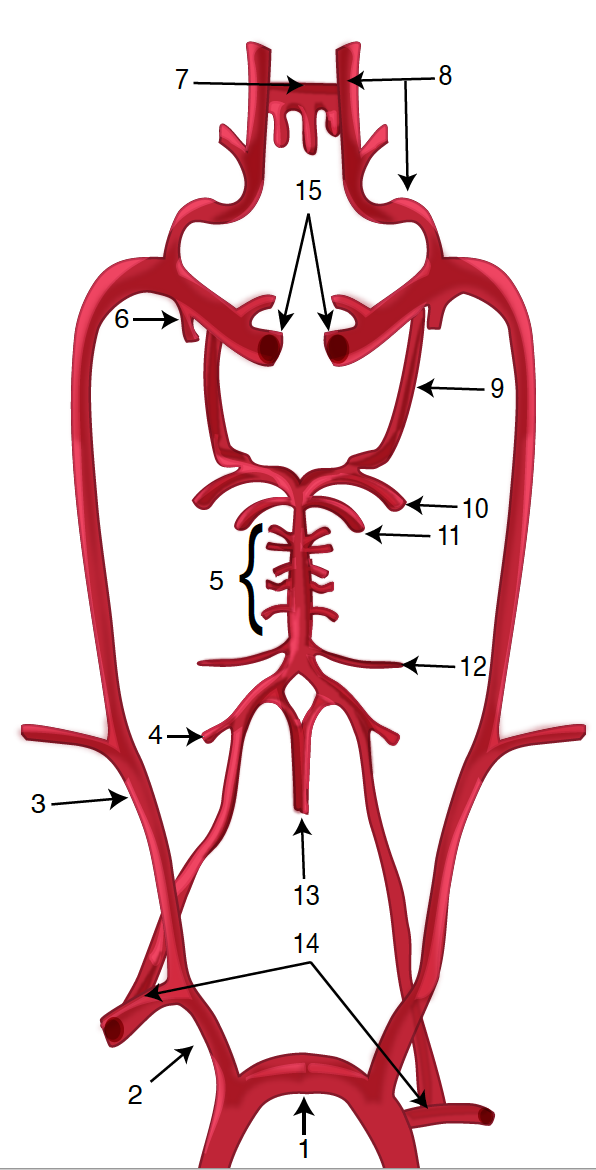

PCA is subdivided in:

- P1: Pre-communicating

- P2: Post-communicating

- P3: Quadrigeminal

- P4: Calcarine

ACA, MCA, and PCA harbor important perforating branches that supply vital structures such as the pituitary gland and its infundibular stalk, the optic chiasm, hypothalamus and thalamus, midbrain and basal ganglia.

Embryology

The internal carotid arteries (ICAs) develop from the third aortic arches, the dorsal aortae, and a plexiform primordial vascular network near the developing fore- and mid-brain.[3] The third aortic arches appear on day 28 as the first and second arch progressively involute. The proximal segment of ICA arises from the third aortic arch while the distal one emanates from the cranial prolongation of the dorsal aortae.

The primitive ICAs divide into cranial (forerunner of the future anterior cerebral artery) and caudal divisions (precursor of the Pcom A). The cranial divisions initially end as the primitive olfactory arteries and ultimately give rise to the definitive anterior cerebral arteries (ACAs), and to the anterior choroidal and middle cerebral arteries. The anterior communicating artery (ACom A) is formed from a plexiform vascular network that coalesces in the midline and connects the two developing anterior cerebral arteries.

The caudal ICA divisions anastomose with the dorsal longitudinal neural arteries. Normally, the caudal divisions regress to form the posterior communicating arteries (PCom As) while the paired dorsal longitudinal neural arteries fuse in the midline to become the basilar artery. The vertebral arteries arise from the coalescing of the cervical intersegmental arteries and later anastomose with the basilar artery. As the definitive vertebral-basilar circulation matures, it annexes the posterior cerebral arteries and their proximal connections to the anterior circulation partially involute.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The arterial vasculature supplies distinct brain territories.[4] The following are the main cerebral arteries, their perforating branches, and related supplied territory.

Anterior Cerebral Artery, AChaA, and its Branches

- The recurrent artery (of Heubner) is the largest artery arising from A1 or proximal A2.[5] It passes above and laterally to the optic chiasm and penetrates the anterior perforated substance. The recurrent artery supplies the head of the caudate nucleus, anterior third of the putamen, anterior part of the globus pallidus externus, anteroinferior portion of the anterior limb of the internal capsule, and the uncinate fasciculus, and, rarely, the anterior hypothalamus.

- Basal perforating arteries (medial lenticulostriate arteries) arising from ACA and Acom A supply the anterior perforated substance, the dorsal surface of the optic nerve and optic chiasm, the optic tract, the suprachiasmatic portion of the hypothalamus, the rostrum of the corpus callosum, the lower surface of the frontal lobe and the medial part of the Sylvian fissure.[6]

The Peri-callosal artery is the distal part of the artery surrounding the corpus callosum. It gives rise to its largest branch: the callosomarginal artery. The callosomarginal artery is recognizable as it courses in or near the cingulate sulcus. Both callosomarginal and distal peri-callosal artery give 5 main cortical branches. They are orbitofrontal, frontopolar, internal frontal, paracentral and parietal arteries. The cortical branches supply the basal surface of the frontal lobe, the superior frontal gyrus and the anterior two-thirds of the medial hemisphere (including the pre-central, central and post-central gyri). Some distal ACA may supply part of the contralateral hemisphere.

Anterior Choroidal Artery

The anterior choroidal artery (AChA) is a small but relatively constant vessel that arises from the posteromedial aspect of the supra-clinoid ICA a short distance above the PCom A origin. The AChA may exist either as a single trunk or a plexus of small vessels. AChA territory is variable and may include the optic tract, the posterior limb of the internal capsule, cerebral peduncle, choroid plexus, and medial temporal lobe.[7][8][7]

Middle Cerebral Artery

The proximal segment (M1) courses laterally to the optic chiasm to reach the medial entrance of the Sylvian fissure. During its journey, it describes two parts: pre and post bifurcation. This main trunk mainly bifurcates but, in some instances, may trifurcate. M1 harbors perforating branches, named lateral lenticulo-striate arteries, which supply most of the caudate nucleus, internal capsule, basal ganglia. Its cortical branches supply the anterior pole of the temporal lobe. The insular segment (M2) consists of 6 to 8 main arteries that lie over the insula and end on top of the circular sulcus. The distal segments M3 and M4 lie from the surface of the lateral cerebral fissure to most of the lateral surface of the brain. Its cortical branches are orbitofrontal, pre-frontal, pre and postcentral sulcus, parietal, angular, temporal, and temporal-occipital arteries. M3 and M4 territory cover almost the entire lateral surface of the brain. Although anastomoses are developed between the ACA, MCA and PCA arterial territories, watershed areas exist on the cortical surface leading to vulnerable brain areas during hypotensive events.

Posterior Cerebral Artery

From the basilar bifurcation to the junction with Pcom A, the proximal segment (P1) of PCA gives numbers of important perforating branches that supply the brainstem, thalamus, oculomotor and trochlear nuclei. P2 courses between the junction and the posterior aspect of the midbrain where it gives thalamoperforating, thalamogeniculate, peduncular perforating, posterior choroidal and posterior temporal arteries. The distal part of PCA (P3 and P4) extends from the quadrigeminal plate to the calcarine fissure where they supply the occipital lobe, part of the parietal and temporal lobe and the posterior third of the medial brain hemisphere.

Vertebrobasilar System

The intradural portion of the vertebral artery (VA) courses anteromedially through the foramen magnum, runs superomedially toward the midline where the two VAs unite to form the basilar artery (BA).[9] During its journey to BA, VA gives the posteroinferior cerebellar Artery (PICA), the anterior spinal artery which supplies the upper spinal cord, lateral medulla, tonsils, the vermis, and the inferior cerebellar hemisphere.[10]

From the confluence of the VAs, the Basilar courses superiorly in front of the medulla, pons and bifurcate at the junction pons/mesencephalon where it gives the posterior cerebral arteries. Along its course, BA gives the anterior inferior cerebellar arteries (AICA), pontine perforating branches and the superior cerebellar arteries (SCA). BA supplies the brainstem, midbrain, part of the thalamus, posterior internal capsule, the mid- and upper cerebellum and vermis.

Physiologic Variants

Variations in the origin, course, and position of arteries are common, whereas variations in size are rare. Developmental anomalies during angiogenesis lead to reported cases of hypoplasia, atresia, agenesis, absence, duplication, and fenestration.

Surgical Considerations

Vascular anomalies such as arteriovenous malformations or aneurysms necessitate surgical treatment. Perfect knowledge of the brain vasculature is mandatory in the pre-operative assessment of vascular diseases. In this pre-operative assessment, an armamentarium of studies can be used such as angioscanner, digital subtraction angiogram (DSA), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA). Of those, the angiogram represents the exam of choice.[11]

Clinical Significance

Abnormalities within the arterial wall, obstruction in the vessel lumen or arteriovenous malformations may predispose to an imbalance in the cerebral hemodynamic leading to an acute onset of neurologic symptoms.

Intracranial Aneurysms

An aneurysm is a focal ballooning of the arterial vessel due to weakness within its wall. Rupture of an intracranial aneurysm is responsible for approximately 80% of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Although all arterial vessels can be affected, the anterior circulation is the most involved. Hemodynamic stress at the arterial bifurcation is the main determinant in the aneurysm formation.

Arteriovenous Malformations (AVM)

AVM is a congenital malformation characterized by an abnormal collection of blood vessels in which the arterial blow flow directly into veins without the normal capillary bed. There is an increased risk of rupture of the nidus leading to intraparenchymal hemorrhage.

Stroke

Stroke is an occlusive cerebrovascular disease due to a distal thrombus or migrated emboli. The inadequate brain perfusion leads to focal areas of brain infarction. Thrombolytic therapy in the early hours of the stroke onset can restore the brain perfusion.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagram of the Brain Blood Circulation. Each number corresponds to the following neuroanatomy: 1) aortic arch; 2) brachiocephalic artery; 3) common carotid artery; 4) posterior inferior cerebellar artery; 5) pontine arteries; 6) anterior choroidal artery; 7) anterior communicating artery; 8) anterior cerebral artery; 9) posterior communicating artery; 10) posterior cerebral artery; 11) superior cerebellar artery; 12) anterior inferior cerebellar artery; 13) anterior spinal artery; 14) arches of vertebral arteries; and 15) internal carotid arteries.

Contributed by O Kuybu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diagram of the Posterior Cerebral Artery and its Branches. Each number corresponds to the following neuroanatomy: 1) basilar artery; 2) superior cerebellar artery; 3) posterior cerebral artery; 4) thalamic subthalamic arteries; 5) posterior communicating artery; 6) internal carotid artery; 7) polar artery of thalamus; 8) posterior choroidal artery; 9) thalamogeniculate artery; 10) anterior inferior temporal artery; 11) posterior inferior temporal artery; 12) occipitotemporal artery; 13) calcarine arteries; and 14) occipitoparietal artery.

Contributed by O Kuybu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Rhoton AL Jr. The supratentorial arteries. Neurosurgery. 2002 Oct:51(4 Suppl):S53-120 [PubMed PMID: 12234447]

Kiserud T, Acharya G. The fetal circulation. Prenatal diagnosis. 2004 Dec 30:24(13):1049-59 [PubMed PMID: 15614842]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKatz DA, Marks MP, Napel SA, Bracci PM, Roberts SL. Circle of Willis: evaluation with spiral CT angiography, MR angiography, and conventional angiography. Radiology. 1995 May:195(2):445-9 [PubMed PMID: 7724764]

Karatas A, Coban G, Cinar C, Oran I, Uz A. Assessment of the Circle of Willis with Cranial Tomography Angiography. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2015 Sep 6:21():2647-52. doi: 10.12659/MSM.894322. Epub 2015 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 26343887]

Vellore Y, Madan A, Hwang PY. Recurrent artery of Heubner aneurysm. Asian journal of neurosurgery. 2014 Oct-Dec:9(4):244. doi: 10.4103/1793-5482.146658. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25685237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLama S, Dolati P, Sutherland GR. Controversy in the management of lenticulostriate artery dissecting aneurysm: a case report and review of the literature. World neurosurgery. 2014 Feb:81(2):441.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2012.12.006. Epub 2012 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 23246740]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTanriover N, Kucukyuruk B, Ulu MO, Isler C, Sam B, Abuzayed B, Uzan M, Ak H, Tuzgen S. Microsurgical anatomy of the cisternal anterior choroidal artery with special emphasis on the preoptic and postoptic subdivisions. Journal of neurosurgery. 2014 May:120(5):1217-28. doi: 10.3171/2014.1.JNS131325. Epub 2014 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 24628614]

Javed K, M Das J. Neuroanatomy, Anterior Choroidal Arteries. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30844216]

Gunnal S, Farooqui M, Wabale R. Anatomical Variability in the Termination of the Basilar Artery in the Human Cadaveric Brain. Turkish neurosurgery. 2015:25(4):586-94. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.12812-14.0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26242336]

Mehinovic A, Isakovic E, Delic J. Variations in diameters of vertebro-basilar tree in patients with or with no aneurysm. Medical archives (Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina). 2014:68(1):27-9 [PubMed PMID: 24783907]

Parry PV, Ducruet AF. Four-dimensional digital subtraction angiography: implementation and demonstration of feasibility. World neurosurgery. 2014 Mar-Apr:81(3-4):454-5. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.01.009. Epub 2014 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 24456826]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence