Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC, Lymphoepithelioma)

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC, Lymphoepithelioma)

Introduction

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC), previously known as lymphoepithelioma, is a malignancy arising from the epithelium of the nasopharynx. Endemic to China, the malignancy shows a variable rate of occurrence ranging from high incidence in the Southern part of China to a low rate in the White population and Northern China with an incidence ranging from 15 to 50 per 100,000. A complex interplay of genetic susceptibility and Epstein Barr virus (EBV) infection is responsible for the disease.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

An interplay of environmental factors, genetic structure, and EBV infection is involved in the etiology of the disease. Environmental factors, including smoking in the western population and nitrosamines containing food agents, have been considered to have an involvement. Secondly, the genetic structure of the demographics involved also plays a vital role, as explained by the overwhelming incidence in the Chinese population. Lastly, EBV infection, coupled with genetic susceptibility, has shown a substantial relevance to the disease.[2][3]

Epidemiology

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is highly endemic to Southern China, Malay, and Indonesian population along with people from Southeast Asia. The rate varies from a minuscule value of less than 1 per 100,000 individuals in non-endemic areas to a high value of 25 to 30 and 15 to 20 males and females per 100,000 individuals in endemic areas, respectively.[4]

Pathophysiology

The development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma depends on multiple factors, such as genetic susceptibility, environmental factors, and infections such as Epstein-Barr virus (EPV) infection. Many studies linked multiple genes to the pathogenesis of the NPC; one of these genes is a region in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes at chromosome 6. Other genes have been identified in different locations on different chromosomes such as 13q12, 3q26, 5p15, 6p21, and 9p21.[5] Other than the host genes, EBV is highly associated with NPC. Many studies illustrate multiple processes and mechanisms that EBV can activate or inhibit in the host cell while transforming it into a cancer cell. EBV affects the cells by bringing its encoded-proteins or RNA molecules that affect host cells, and these molecules could be summarized but not restricted to:

- Latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1): it is a membrane protein encoded by the virus, and plays a major role in inducing tumorigenesis. Its main effect is related to the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB). Activation of NF-kB will lead to affect many other proteins that play an important role in cell division, adhesion, cell differentiation, cell survival. In addition to NF-kB, LMP1 affects many other factors, proteins, and DNA regulation processes that affect the oncogenesis process, such as TP53, EGFR, VEGF, stemness-related genes, fibronectin, etc. LMP1 is associated with poor prognosis.

- Latent Membrane Protein 2A (LMP2A): it is a membrane oncoprotein that is encoded in the viral DNA, it has a role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition, hence invasion and migration.

- MicroRNAs (miRNA): it is non-coding RNA molecules that have a function in the regulation of the gene expression process, and hence affect the cell functions and division. EBV expresses a high level of miRNA, such as complementary strand transcripts, i.e., BamHI-A rightward transcripts (BARTs), which is highly associated with the NPC pathogenesis, e.g., miR-BART3, miR-BART7, and miR-BART13. Since these molecules are copious and could be excreted extracellularly, these miRNA can be used as a biomarker for diagnosis and predicting prognosis.

- Other molecules: such as metastatic tumor antigen 1 (MTA1), which is correlated with tumor metastasis. Epstein–Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein is a nuclear protein that is associated with transcription of the virus and the lymphatic metastasis.[6]

Histopathology

Histopathological evaluation can elucidate in which category does the tumor fall. On histopathological grounds, Nasopharyngeal carcinoma can be categorized into three main sub-groups as per WHO classification:

- Keratinizing type (20% to 25%)

- Non-keratinizing: this type is mainly associated with EBV. It is subdivided to 2 subgroups:[5]

- Non-keratinizing undifferentiated type (60% to 65%)[7]

- Non-keratinizing differentiated type (10% to 15%)

History and Physical

Patients can have variable presentations depending on the area of involvement of the disease.

- Nasal symptoms: This subset involves symptoms ranging from nasal obstruction, blood-tinged nasal discharge, and post-nasal drip to denasalization of voice and cacosmia. Symptomatology is proportionate to the size of growth and the extent of local involvement. Around 80% of the individuals suffering from the disease present with nasal symptoms

- Otological symptoms: Patients present with symptoms secondary to Eustachian tube blockage, i.e., conductive hearing loss, effusions and fullness, and tinnitus. Half of the patients with NPC have some form of otological complaint during the disease caused because of the growing mass obstructing the outflow of the Eustachian tube.

- Neurological symptoms: Intracranial extension is prevalent among 8% to 12% of the demographic — various forms of cranial nerve involvement present with the associated symptom. The most commonly involved nerve is the abducens nerve.[8]

- Nodal involvement: One of the most common presenting features would be an enlarged neck node. Lymph nodes of the apex of the posterior triangle and the upper jugular are most commonly involved initially. Supraclavicular nodes are the last to be involved and are a sign of advanced disease.[9]

Distant metastasis and Paraneoplastic Syndrome

Symptoms associated with distant spread are rarely presented to the primary care provider. The most significant spread includes the liver and lungs. It is sometimes difficult to assess the primary site of malignancy when metastatic pulmonary lesions are observed. PET scan aids in the differentiation of the two. Secondly, a handful of cases present with symptoms of dermatomyositis. A 10-year retrospective review has shown an association of NPC in patients with dermatomyositis.[10]

Evaluation

Lab Investigations

- Baseline investigations which include complete blood count, renal and liver function tests can be sent for initial scrutiny. An abnormality would be detected in cases where a hepatic extension is suspected along with a deterioration in renal function as the tumor divides at a rapid pace.

- Epstein Barr virus has been invariably involved in the pathogenesis of the disease process. To establish an association, serum IgA levels are to be ordered. These carry both diagnostic and prognostic significance for the disease process.[10]

Imaging Studies

- CT scan: A local tumor can be visualized extending from the roof of the pharynx. CT scan is the modality of choice as far as bone invasion, and intracranial extension is to be visualized. However, radiation exposure and its limited value in terms of soft tissue extension and nodal metastasis make MRI the preferred modality (see Video. Radiologic Imaging Study, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma).

- MRI scan: MRI is the superior modality for assessing the tumor extension into the musculature and the nodal metastasis. The tumor bulk, along with local invasion, can be easily visualized and does not pose any threat of radiation.

- PET scan: It is the modality of choice for assessing remission and for investigating recurrence. PET-CT scan can augment the extent of distant metastasis as it is a whole-body scan. However, MRI can provide a greater level of local delineation, making it still the investigation of choice for local spread.[11]

Endoscopic Evaluation and Histopathological Analysis

- The tumor can be visualized via nasopharyngoscopy, and the local extension along with tumor size can be assessed, and biopsy can be taken. However, the assessment may be hindered if the mass is too large to access the nasal passage.

Treatment / Management

The mainstay of treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma is radiotherapy in locoregional lesions as the non-keratinizing variety is highly radiosensitive. Surgical intervention is limited to salvage procedures in recurrent diseases, whereas chemotherapy is preferred concomitantly with radiation in advance stages.

Radiotherapy

Radiation is the management of choice for the locoregional lesion. Radiotherapy is effective in all cases except those for distant metastasis hence from stage I to stage IVA. NPC shows a tendency for quick spread regionally, especially as the nasopharynx is a small cavity so spread to paranasopharyngeal spaces, musculature, and nodes common. Also, progressively involving the contralateral side is not a rare occurrence. Consequently, a dose of approximately 65 Gy for primary tumor with 50 to 55 Gy is also necessary for nodal negative necks.

A recent innovation in the delivery system employed for radiation is intensity modulation or intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). The system is equipped with a CT taking slices of the area involved. The physician specifies the targeted area of the beam and modulates the intensity of the beam employed.[12]

Brachytherapy is another innovative technique for targeted radiotherapy. The technique employed is the implantation of gold grains or iridium implants, jacketed for localized radiotherapy, via a split incision of the soft palate. The technique is useful for localized tumor bulk that has not shown any intracranial extension. The technique spares any local vital organ damage.

Radiotherapy is also employed when treatment failure or recurrence is seen. It has been proven useful in both local recurrence and nodal failures. In such cases, brachytherapy is considered keeping in mind the friability of the local tissue, the general condition of the patient, and the impact on vital organs of the region.[3][11]

Chemotherapy

NPC is highly chemo and radiosensitive. In advanced locoregional disease, concomitant chemoradiotherapy is the mainstay of management. The disease responds better with induction, and concurrent therapy is significant in shrinking the tumor bulk. The commonest agent used as the initial line of chemotherapeutic intervention is cisplatin. The standard of care is a dose of 100 mg every third week.

Chemotherapy is also the option of choice when distant metastasis is involved. NPC with distant poly-metastasis is offered palliative chemotherapy. The agents of choice are cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. With recent advances, there are a number of chemotherapeutic agents that are available for the continuation of therapy. However, the median survival rate is not more than a year.[3][11]

Surgical Intervention

Surgical intervention is employed only as a salvage option. The nasopharynx is a small and deep area that is hard to access, thus making the surgical approach difficult and may be inappropriate. However, when the locally recurring disease is encountered, patients should be given the option of surgical intervention. Surgery is also one of the key modes of management for distant oligo-metastasis in conjunction with radiotherapy and radio ablation.[13][14]

Nasopharyngectomies are carried out by a number of approaches, and the approach decided should be tailored in accordance with the expertise of the surgeon and the general condition of the patient. The following are some of the popular approaches to the cavity.

- Inferior approach - via transpalatal incision

- Lateral approach - via the lateral skull base

- Inferolateral approach

- Midfacial degloving

- Endoscopic approach

Radical neck dissections are often done accompanying the procedures mentioned above, where extensive neck involvement is seen. Also, in recurring disease, especially nodal recurrence, radical neck dissection is done as a component of salvage therapy.

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma is based on regional lesions involving the nasopharynx and mimicking the symptomatology. Categorization can be made on the nature of the lesion in the following manner:

Benign Conditions

- Nasopharyngeal polyposis

- Angiofibromas

Malignant Lesions

- Lymphomas,

- Salivary gland tumors

- Sinonasal carcinomas

- Malignant mucosal melanomas

Staging

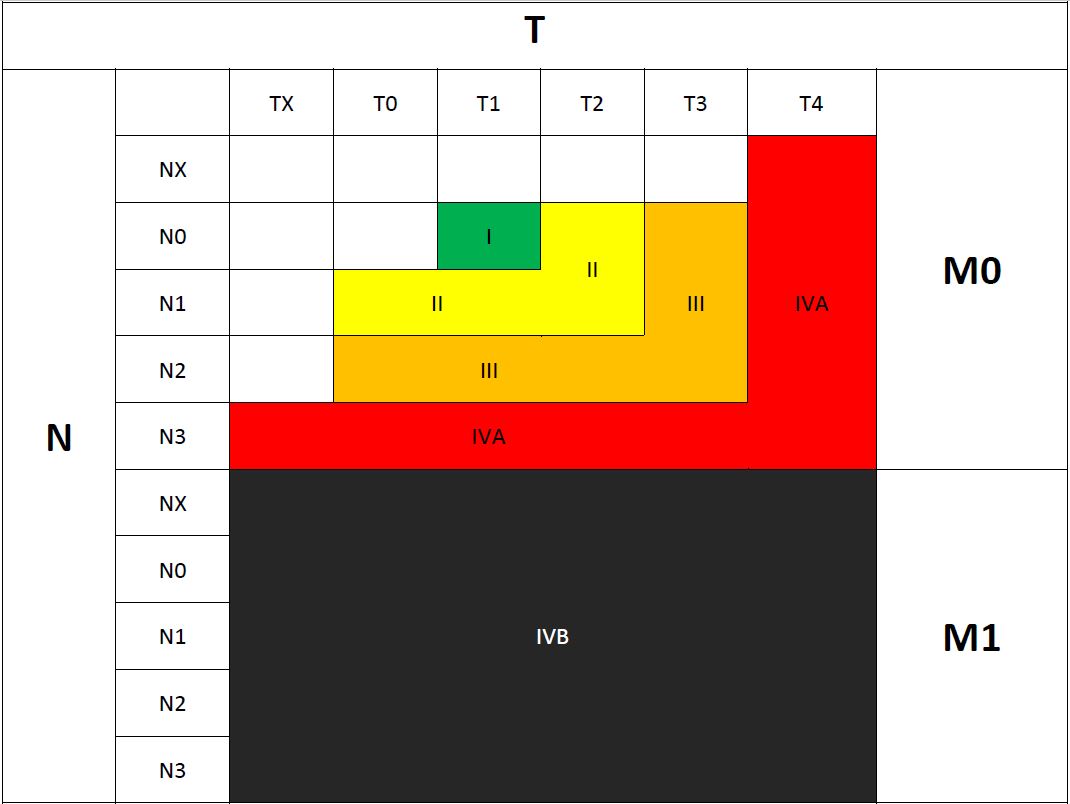

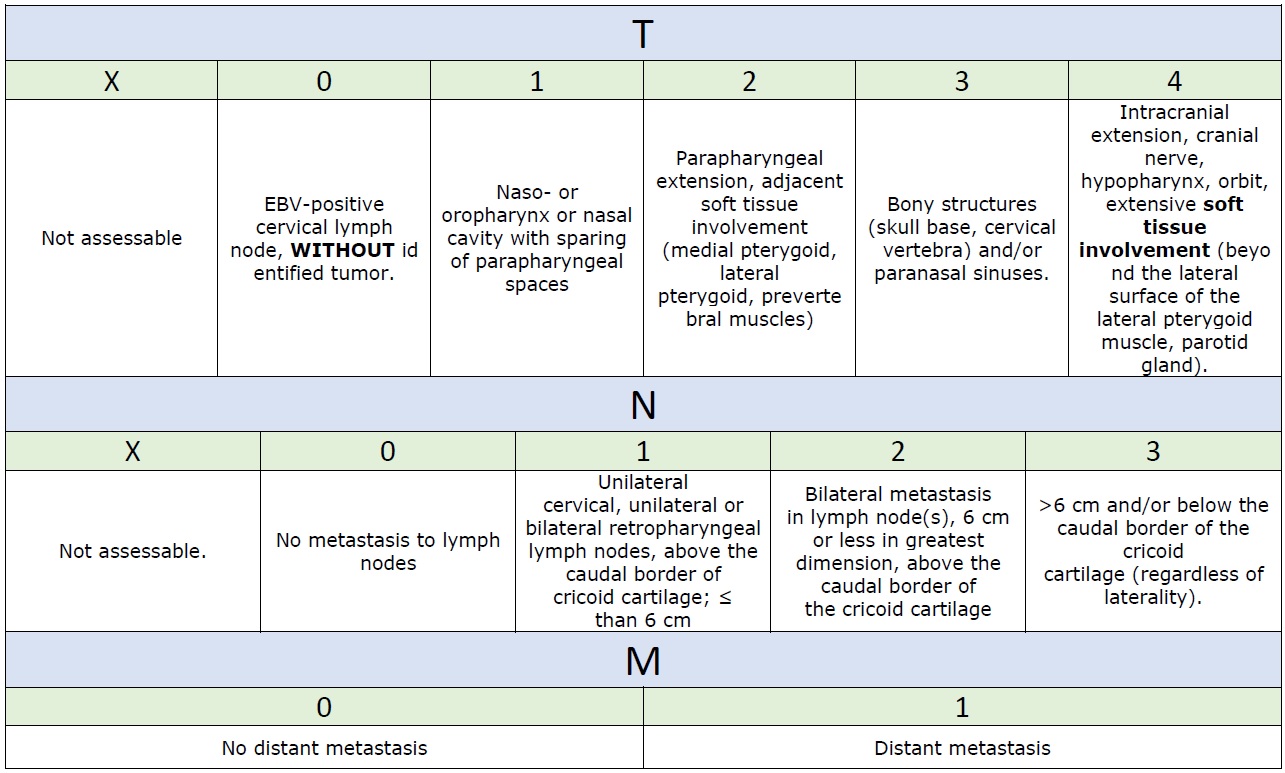

The nuances in imaging techniques and the improved outcomes associated with optimum therapy have caused the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) to reevaluate the staging process. This tumor is stagged according to the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor, node, metastasis (TNM) system. The 7th edition of the UICC/JNCC staging system was replaced by the 8th edition (last update) in 2016. As per the last update of classification, the TNM staging has been explained as the following criteria (Table 1 summarize the staging groups, Table 2 summarize the UICC/AJCC 8th edition staging of NPC):[5] See Tables. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Staging Groups and Summary of UICC/AJCC Staging of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma.

T: which refers to the local size or extent of the tumor

- TX: Not assessable.

- T0: EBV-positive cervical lymph node, WITHOUT identified tumor. This stage was introduced in the latest update of the staging.

- T1: Naso- or oropharynx or nasal cavity with sparing of parapharyngeal spaces.

- T2: Parapharyngeal extension, adjacent soft tissue involvement (medial pterygoid, lateral pterygoid, prevertebral muscles). This muscular specific description was revised in the 8th edition of the AJCC staging system.

- T3: Bony structures (skull base, cervical vertebra) and/or paranasal sinuses.

- T4: Intracranial extension, cranial nerve, hypopharynx, orbit, extensive soft tissue involvement (beyond the lateral surface of the lateral pterygoid muscle, parotid gland). The "soft tissue" description here replaces the "infratemporal fossa and masticator space" in the previous edition.

N: refers to the regional lymph node metastasis.

- NX: Not assessable.

- N0: No metastasis to lymph nodes

- N1: Unilateral cervical, unilateral or bilateral retropharyngeal lymph nodes, above the caudal border of cricoid cartilage; not more than 6 cm

- N2: Bilateral metastasis in lymph node(s), 6 cm or less in greatest dimension, above the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage

- N3: >6 cm and/or below the caudal border of the cricoid cartilage (regardless of laterality). This stage was different from the previous staging edition, and they merged the N3a and N3b into one category N3

M: refers to distant metastasis.

- M0: No distant metastasis

- M1: Distant metastasis

Staging groups: The 8th edition of AJCC update in groups involve the fourth group only, previous IVA and IVB groups were merged together in the new IVA group, and subsequently, the old IVC group was upgraded to be the new IVB as the following:

- I: T1 N0 M0

- II: T2 N0–1 M0, T0–1 N1 M0

- III: T3 N0–2 M0, T0–2 N2 M0

- IVA: T4 or N3 M0

- IVB: Any T, any N, M1

Prognosis

The overall prognosis and the 5-year survival rate has definitely improved since the advent of nuances in the radiotherapy techniques. This has drastically decreased the mortality and morbidity associated with illness from a reported 5-year survival of 20% to 40% to approximately 70% in the past decade.[15]

However, the predicting value for prognosis in the classic anatomical staging system is not sufficient nor accurate. Adding the EBV DNA status of the patient to the new (8th edition) makes this system more accurate for the estimation of the prognosis. In addition, other studies show other efficient biomarkers for assessing the prognosis of this tumor, such as miRNA and DNA methylation.[5]

Complications

Lesions can have local complications, including obstruction of Eustachian tubes causing otitis media with effusion (OME), persistent nasal obstruction, and obstruction of an oropharyngeal airway. Mass effect causing blockage of oropharynx impedes swallowing, and if it remains unchecked, its progression may lead to blockage of the airway. Intracranial extension and involvement of cranial nerves are debilitating and can have a lifelong disability even after management.[16]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients endemic to prevalent areas should be more vigilant regarding the symptoms of the disease. Moreover, the demographics of the western population having environmental factors (smoking, etc.) associated with NPC should also be educated regarding their hazardous effects. Also, the subset of people having genetic susceptibility along with recurrent EBV infection should have a higher index of suspicion for the disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

- Nasopharyngeal carcinoma is a malignancy having a variable incidence depending on the region.

- Endoscopic biopsy should be the first and foremost step for the evaluation of the lesion.

- NPC has a high index of susceptibility to radiotherapy; hence should be considered in almost all forms of the disease at the initial presentation. Coupling the effectiveness of this mode of management with difficulty associated with the surgical approach to the region makes radiotherapy the therapy of choice.

- In advanced cases, chemotherapy is given concomitantly to produce optimum results. The drug of choice is cisplatin initially, given concomitantly with radiotherapy.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Endemic areas have made strides in this regard as they have increased their index of suspicion towards such malignancies at the primary care physician level. After diagnosis, a radiotherapist and oncologist should educate the patient regarding the favorable outcome associated with strict adherence with the program. Prolong therapy has complications of itself that can be managed in follow-up clinics. Also, patients having the psychological burden, benefit from structured support groups and psychologist sessions.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Radiologic Imaging Study, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Radiologic imaging study of a 53-year-old male patient who had been operated on for a nasopharyngeal carcinoma 5 years ago.

Contributed by M Özdemir, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Du T, Xiao J, Qiu Z, Wu K. The effectiveness of intensity-modulated radiation therapy versus 2D-RT for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2019:14(7):e0219611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219611. Epub 2019 Jul 10 [PubMed PMID: 31291379]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSun L, Wang Y, Shi J, Zhu W, Wang X. Association of Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus LMP1 and EBER1 with Circulating Tumor Cells and the Metastasis of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Pathology oncology research : POR. 2020 Jul:26(3):1893-1901. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00777-z. Epub 2019 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 31832991]

Adoga AA, Kokong DD, Ma'an ND, Silas OA, Dauda AM, Yaro JP, Mugu JG, Mgbachi CJ, Yabak CJ. The epidemiology, treatment, and determinants of outcome of primary head and neck cancers at the Jos University Teaching Hospital. South Asian journal of cancer. 2018 Jul-Sep:7(3):183-187. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_15_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30112335]

Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN. The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chinese journal of cancer. 2011 Feb:30(2):114-9 [PubMed PMID: 21272443]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChen YP, Chan ATC, Le QT, Blanchard P, Sun Y, Ma J. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet (London, England). 2019 Jul 6:394(10192):64-80. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30956-0. Epub 2019 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 31178151]

Zhang H, Wang J, Yu D, Liu Y, Xue K, Zhao X. Role of Epstein-Barr Virus in the Development of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Open medicine (Warsaw, Poland). 2017:12():171-176. doi: 10.1515/med-2017-0025. Epub 2017 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 28730175]

Peng G, Wang T, Yang KY, Zhang S, Zhang T, Li Q, Han J, Wu G. A prospective, randomized study comparing outcomes and toxicities of intensity-modulated radiotherapy vs. conventional two-dimensional radiotherapy for the treatment of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiotherapy and oncology : journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 2012 Sep:104(3):286-93. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.08.013. Epub 2012 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 22995588]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMo HY, Sun R, Sun J, Zhang Q, Huang WJ, Li YX, Yang J, Mai HQ. Prognostic value of pretreatment and recovery duration of cranial nerve palsy in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Radiation oncology (London, England). 2012 Sep 7:7():149. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-149. Epub 2012 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 22958729]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBatsakis JG, Solomon AR, Rice DH. The pathology of head and neck tumors: carcinoma of the nasopharynx, Part 11. Head & neck surgery. 1981 Jul-Aug:3(6):511-24 [PubMed PMID: 7251374]

Teoh JW, Yunus RM, Hassan F, Ghazali N, Abidin ZA. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma in dermatomyositis patients: A 10-year retrospective review in Hospital Selayang, Malaysia. Reports of practical oncology and radiotherapy : journal of Greatpoland Cancer Center in Poznan and Polish Society of Radiation Oncology. 2014 Sep:19(5):332-6. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2014.02.005. Epub 2014 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 25184058]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlanchard P, Nguyen F, Moya-Plana A, Pignon JP, Even C, Bidault F, Temam S, Ruffier A, Tao Y. [New developments in the management of nasopharyngeal carcinoma]. Cancer radiotherapie : journal de la Societe francaise de radiotherapie oncologique. 2018 Oct:22(6-7):492-495. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2018.06.003. Epub 2018 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 30087054]

Lee N, Harris J, Garden AS, Straube W, Glisson B, Xia P, Bosch W, Morrison WH, Quivey J, Thorstad W, Jones C, Ang KK. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma: radiation therapy oncology group phase II trial 0225. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2009 Aug 1:27(22):3684-90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.9109. Epub 2009 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 19564532]

Liu J, Yu H, Sun X, Wang D, Gu Y, Liu Q, Wang H, Han W, Fry A. Salvage endoscopic nasopharyngectomy for local recurrent or residual nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a 10-year experience. International journal of clinical oncology. 2017 Oct:22(5):834-842. doi: 10.1007/s10147-017-1143-9. Epub 2017 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 28601934]

Hay A, Simo R, Hall G, Tharavai S, Oakley R, Fry A, Cascarini L, Lei M, Guerro-Urbano T, Jeannon JP. Outcomes of salvage surgery for the oropharynx and larynx: a contemporary experience in a UK Cancer Centre. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2019 Apr:276(4):1153-1159. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05295-x. Epub 2019 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 30666441]

Li J, Chen S, Peng S, Liu Y, Xing S, He X, Chen H. Prognostic nomogram for patients with Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma incorporating hematological biomarkers and clinical characteristics. International journal of biological sciences. 2018:14(5):549-556. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.24374. Epub 2018 Apr 5 [PubMed PMID: 29805306]

Ho AC, Chan JY, Ng RW, Ho WK, Wei WI. The role of myringotomy and ventilation tube insertion in maxillary swing approach nasopharyngectomy: review of our 10-year experience. The Laryngoscope. 2013 Feb:123(2):376-80. doi: 10.1002/lary.23684. Epub 2012 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 22951935]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence