Crigler Technique for Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Crigler Technique for Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction

Introduction

Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (CNLDO) is defined as the failure of drainage of tears down the nasolacrimal system in the neonatal age group. It results in tearing, which is termed "epiphora." The prevalence of CNLDO is between 5% and 20%.[1][2] A comprehensive study of 4792 infants in Great Britain showed that the prevalence of epiphora in the first year of life was 20%, with 95% of these showing symptoms at one month of age.[1] There is a higher prevalence of CNLDO in premature infants.[3] CNLDO presents bilaterally in 14% to 34% of cases.[4] It has also been shown that anisometropic amblyopia may occur in 10% to 12% of children with CLNDO, so a proper ophthalmic eye examination and cycloplegic refraction are performed in all cases with a careful subsequent follow-up for three to four years.[5][6]

Of interest is the finding of Cassidy in 1952, who noted that there was obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct in 13 of 15 stillborn infants. His postulation that patency of the nasolacrimal duct occurs within the first few days to weeks after birth is a reasonable one.[7]

Children most often present within a few months of birth with epiphora and sometimes mucoid discharge from one or both sides. However, even with symptoms present since birth, patients may present when several years old. Other causes of epiphora in children like epiblepharon, congenital glaucoma, foreign body, corneal infections, and corneal dystrophies need to be excluded. Wheres the Jones 1 test where insertion of fluorescein dye into the eye is followed by the presence of dye in the nose after 5 minutes may be used, it is rarely used now since the clinical history and observation of the tearing, and mucoid discharge generally confirms the diagnosis. Similarly, the dye disappearance test over 5 minutes may also be used, but there may be significant false positive and negative results in infants.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

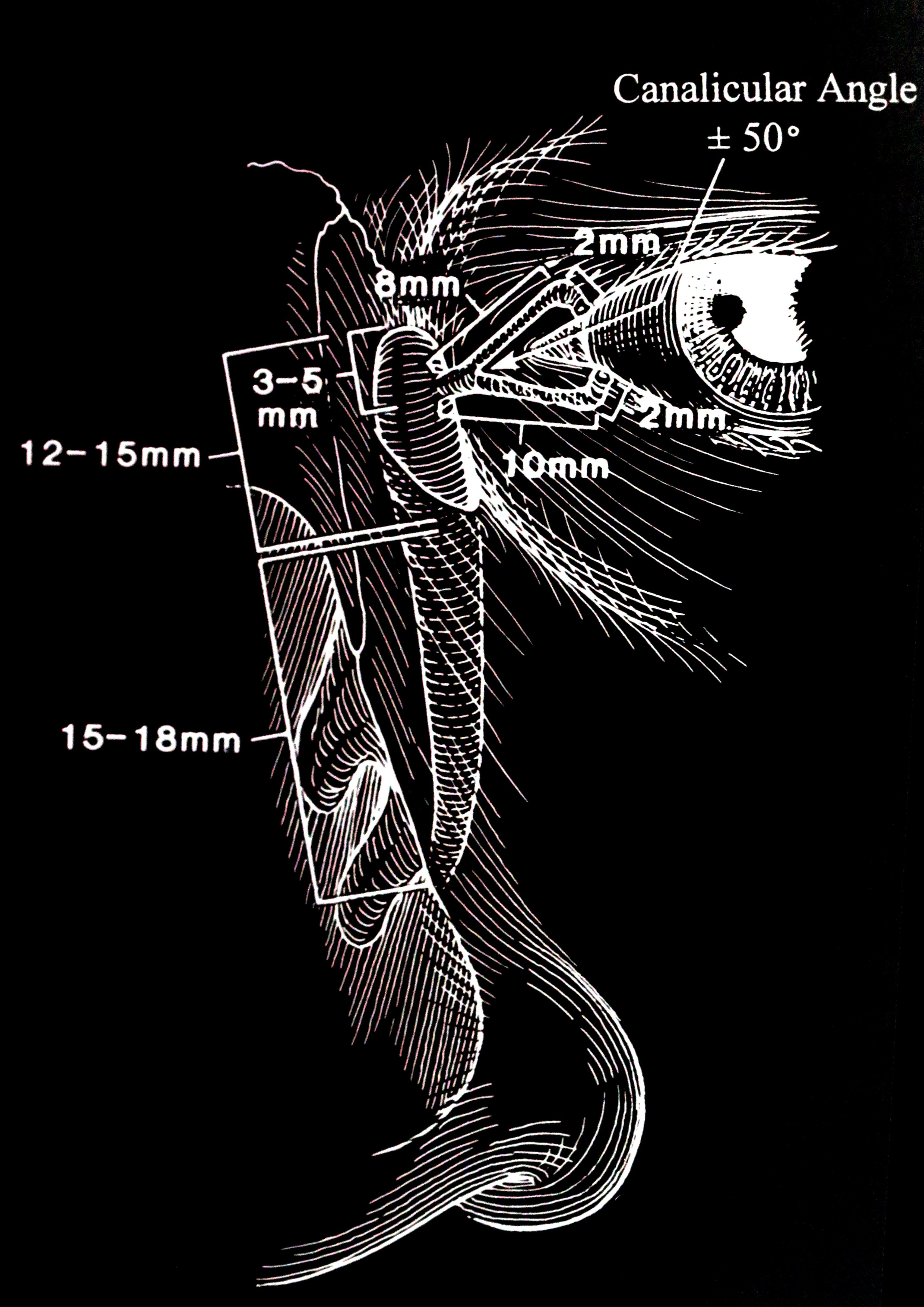

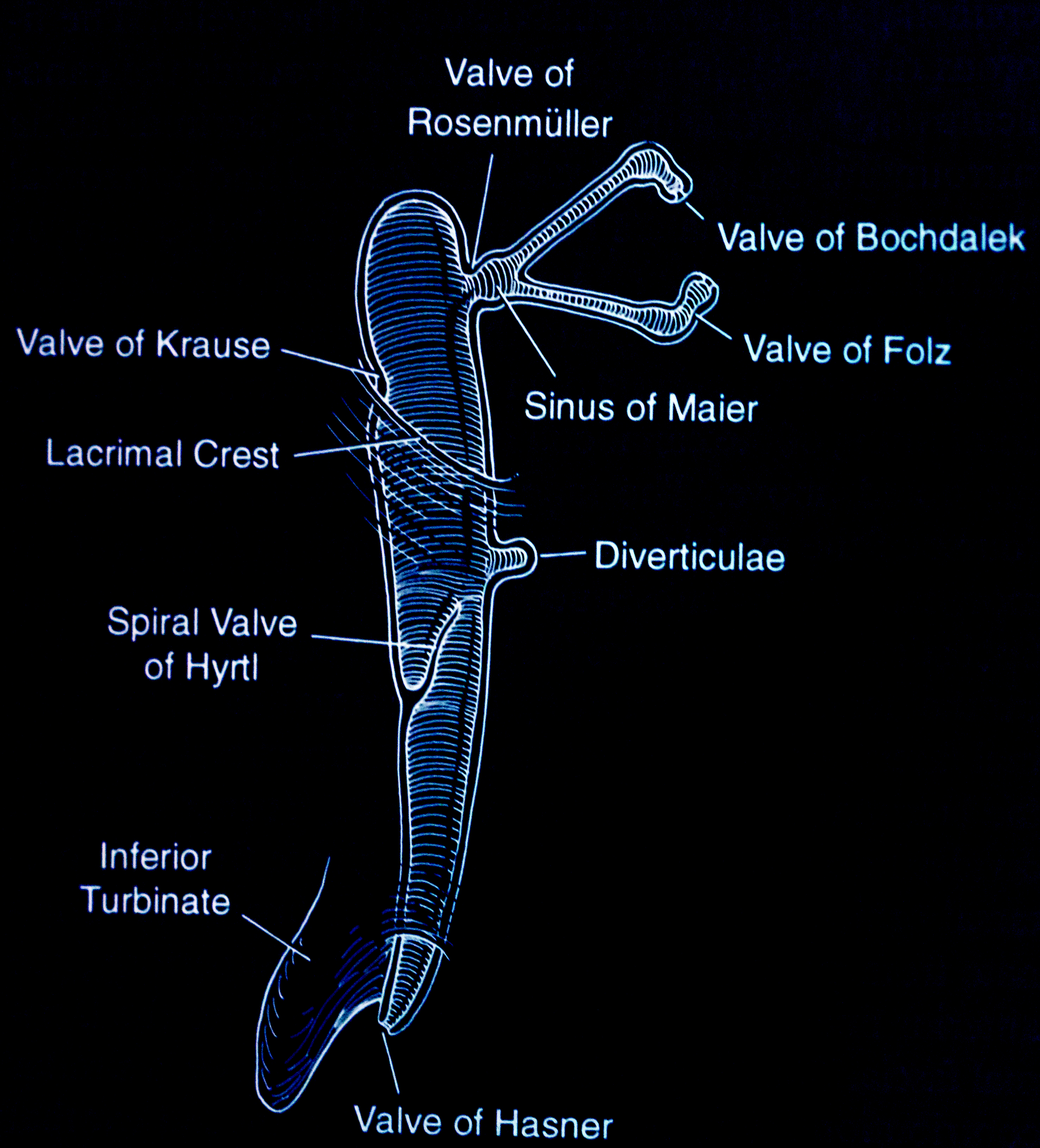

The excretory lacrimal system consists of the puncta, canaliculi, common canaliculi, lacrimal sac, and nasolacrimal duct, which opens at the inferior meatus over a mucosal flap, termed the Hasner valve.(Figure 1 & 2) The commonest causes of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction are:

- Membranous persistence at the distal end of the nasolacrimal duct

- Bony abnormalities with associated narrow inferior bony nasolacrimal canal

- Stenosis of the inferior meatus[8][9]

Although it has been suggested that obstruction at the Hasner valve is more likely to present with mucoid discharge and obstruction closer to the lacrimal sac causes a watery discharge, this has not been our experience.[10]

Natural History of CNLDO

- Spontaneous resolution of CLNDO has been to occur in up to 95% (32% to 95%) of children by the age of 13 months.[11][12][13]

- A non-randomized prospective study of 55 infants showed that spontaneous resolution was seen by three months in 15%, by six months in 45%, by nine months in 71%, and by 12 months in 93% of children.[14]

- Higher spontaneous resolution occurs in the first three months of age (80% to 90%), 68% to 75% in the second three months, and 36% to 57% in the third three months.[12][14]

- Nelson et al. treated one 113 consecutive children with congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction using local massage and topical antibiotic ointment. By eight months, 107 patients were cured (93%) without the need for any other intervention.[15]

- Kakiazaki et al. studied thirty-five lacrimal ducts in 27 patients diagnosed with CNLDO in Japanese infants. They were treated with massage and antibiotic drops. Twenty-nine lacrimal ducts in 21 patients resolved with conservative treatment by age 12 months (82.9%), with 46% of the ducts resolving before the age of six months.[12]

- The Pediatric Eye Disease Investigative Group (PEDIG) compared immediate nasolacrimal duct probing in the office with conservative management for six months and found that 66% of children with obstruction resolved within six months without intervention.[16]

- In children still symptomatic after the first 12 months, a multicenter, randomized trial showed that spontaneous resolution occurs in 44% of these children between the first and second years of life.[17]

- In the presence of bilateral congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction (seen in 12% to 34% of cases), the second eye has been shown to spontaneously resolve within three months of resolution of the first eye.[18]

Management of CNLDO

It is widely accepted that unless there is a mucocele or dacryocystitis, CNLDO is managed conservatively in children for the first 12 months of life in one of two ways:

- Observation

- Massage of the lacrimal sac (Crigler technique)

The Crigler technique seems to have been forgotten in clinical practice, as we observe many surgeons simply observing these patients with no manipulation of the lacrimal sac with the different ways of massaging the sac. Indeed, some studies have stated that the massage technique is of questionable benefit.[19][20] The advantage of using Crigler's technique has been shown by a number of studies:

- Crigler reported 100% success with the use of this technique over a seven-year period, but other details were not presented.

- Price used the Crigler technique in 203 cases of CNLDO in the first year of life and noted a cure rate of 95%.[21]

- A prospective study by Karti et al. introduced a lacrimal sac massage in 28 eyes of infants with CNLDO younger than three months. In the second group of 8 eyes, no massage was applied. They found that 96% of the massage group resolved by age 12 months and 77% resolved in the non-massage group (p = 0.001). Furthermore, the mean age of resolution was 6.8 months in the massage group and 10.3 months in the group without massage.[22]

- Kushner performed a randomized prospective trial on 132 children with CNLDO. He found the massage technique gave a higher resolution rate than simple observation.[23]

- Stolovitch et al. studied 742 children with CNLDO. With the use of "hydrostatic pressure" as described by Crigler.[24] They found that the massage technique was more effective in children younger than 2 months old but found success with children even up to one year of age. They did not have a control group that received no massage, however.

Antibiotics for CNLDO

Antibiotics should only be used to treat active infection and in children with a mucopurulent discharge. The use of prophylactic antibiotics has not shown any improvement in the outcome of patients with CNLDO.[25][26]

Surgical Intervention

- High-pressure Irrigation: High-pressure irrigation of the lacrimal system to open the presumed mucosal obstruction at the inferior end of the nasolacrimal duct has been shown to work with success ranging from 33% to 100%. Alagoz et al. treated 39 eyes with failed conservative treatment and found success of 79% after one attempt and 100% after two attempts. The success was equally good in children below 12 months of age and in those 12 to 18 months old.[27] However, this high-pressure irrigation is rarely performed. Instead, the treatment of failed conservative massage is usually the next treatment in this list: probing.

- Nasolacrimal Duct Probing: It is now accepted that children with persistent symptoms after the age of 12 months should undergo probing of the nasolacrimal system with Bowman probes, usually under general anesthesia. However, some surgeons still perform this procedure in the clinic. Our concern with performing this in a moving child is the risk of trauma to the mucosa of the canaliculus, the common canaliculus, or the lacrimal sac. There are still groups that advocate early probing, which is probing upon presentation, without allowing for spontaneous resolution or resolution with a massage. Studies have shown that resolution rates are as follows:

- Nasolacrimal Duct Probing in Older Children: It is well recognized that the success of probing decreases with the increasing age of the child. Rajabi et al., in a prospective study of 343 children, found 85% success in children aged 2 to 3 years, 63% in children aged 3 to 4 years, and 50% in children 4 to 5 years. Napier et al. reported an overall success of 76% in children aged 0 to 9.8 years with probing. Probing of the nasolacrimal system carries the risk of bleeding, injury to the mucosa with secondary constriction due to fibrosis, and creation of false passage. It has been reported that bleeding from the lacrimal punctum will occur in 20% of patients with the attendant risk of scarring or the creation of a false passage.[17]

- Nasolacrimal Duct Probing with an Endoscopic View of the Lacrimal System: Endoscopes that allow the view down the nasolacrimal system has been designed. When combined with infracture of the inferior turbinate where indicated and with direct visualization and correction of the obstruction, these modern techniques improve success and reduce the risk of having complications.[31][32]

- Repeat Nasolacrimal Duct Probing After Failed Initial Probing: When an initial nasolacrimal duct probing fails, symptoms will redevelop within four to eight weeks. Repeat probing is then recommended. A prospective study found success of 56% after a six-month follow-up period.[33] Katowitz found success in 52% of children aged 6 to 12 months and 18% in children 18 to 24 months. Some of the causes of secondary failures may be related to iatrogenic stenosis and scarring or false passage creation from initial probings, but the incidence of these complications is not known.

- Nasolacrimal Duct Probing and Intubation with Silicone Stent: After one or more failed probing of the nasolacrimal system, most physicians will probe and insert a silicone stent, with or without infracture of the inferior turbinate. The stents are removed from two to six months after intubation. In older children, it has been shown that the success rate is higher if sents are left in for longer than 3 months.[34] Most surgeons will proceed with intubation after an initially failed probing, rather than repeat the probing. Monocanalicular stents have been introduced, which makes the removal of the stent easier in the clinic. Eustis et al., who investigated 186 eyes with CNLDO, found the success with monocanalicular stents to be 93% compared to 78% for bicanalicular stent insertion (p = 0.00653).[35] Primary silicone stent intubation as the initial intervention has been shown to have a success rate of 90% in children aged 6 months to 45 months with the tubes retained for between two and five months.[18] Risks of silicone stent intubation include premature loss of the stent, corneal erosion, conjunctival injury, punctal, and canalicular trauma, the formation of granulomas, and retained silicone stents after attempted removal.

- Balloon Catheter Dilatation: Balloon dilatation of the nasolacrimal duct has been shown to have a success of 77% in patients that have initially failed probing. However, with the intubation of silicone stent in similarly failed probings, the success was found to be 88%.[36] Because of the cost of disposable equipment, balloon catheter dilatation should be used in managing complex CNLDO cases rather than as a primary treatment.

- Dacryocystorhinostomy: In the presence of persistent obstruction, bony obstruction, presence of a dacryocystocele or dacryocystitis, endoscopic or external dacryocystorhinostomy is undertaken.

The above studies confirm that in children up to the age of 12 months, a conservative approach with proper lacrimal sac massage should be the first-line treatment of CNLDO. Crigler first described massage of the lacrimal sac for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in 1923 (Crigler LW. The treatment of congenital dacryocystitis JAMA1923; 81: 23-24). Kushner later performed a randomized prospective study and showed the efficacy of the Crigler technique when compared to no massage application. He acknowledged in his presentation that the technique had been used by others in the past, but he noted that nobody had formally presented the technique at a medical meeting. He does note that "the late Dr. Kipp, however, was a strong advocate of it." He goes on to note that Dr. Kipp discussed the massage of the lacrimal sac in the discussion of a paper in 1908. There is mention of massage by others like Fuchs, Roemer, Crawford, Fage, Norris, and Oliver. So the originator of the technique may never be identified.[23] As the best way to apply the massage is not widely known or practiced, we present the different ways that this technique may be applied.

Indications

The massage technique, as we have illustrated, is indicated in:

- All newborn infants seen with epiphora caused by congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction

- The treatment is commenced in all children when first seen for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction, irrespective of the age of the child.

- The treatment is used even when a child is awaiting a more invasive procedure like probing, intubation, or balloon dilatation.

- If a child has mucoid discharge and is awaiting a dacryocystorhinostomy, the administration of this technique reduces the amount of mucous that persists in the eye during the day

Contraindications

The massage technique is contraindicated in:

- Children presenting with an acute dacryocystitis

- If the cause of the tearing in a child is canalicular scarring or punctal agenesis

Equipment

No specialized equipment is needed for this technique, which is illustrated in the video.

Personnel

One of the parents needs to administer this technique to the nasolacrimal sac and duct.

Preparation

It is best to perform the technique after the child is fed and asleep in the parent's arms.

Technique or Treatment

It is worth reading the original description of the maneuver as described by Mr. Crigler as read before the Section on Ophthalmology at the New York Academy of Medicin on February 19, 1923, and subsequently published in the JAMA in the same year:

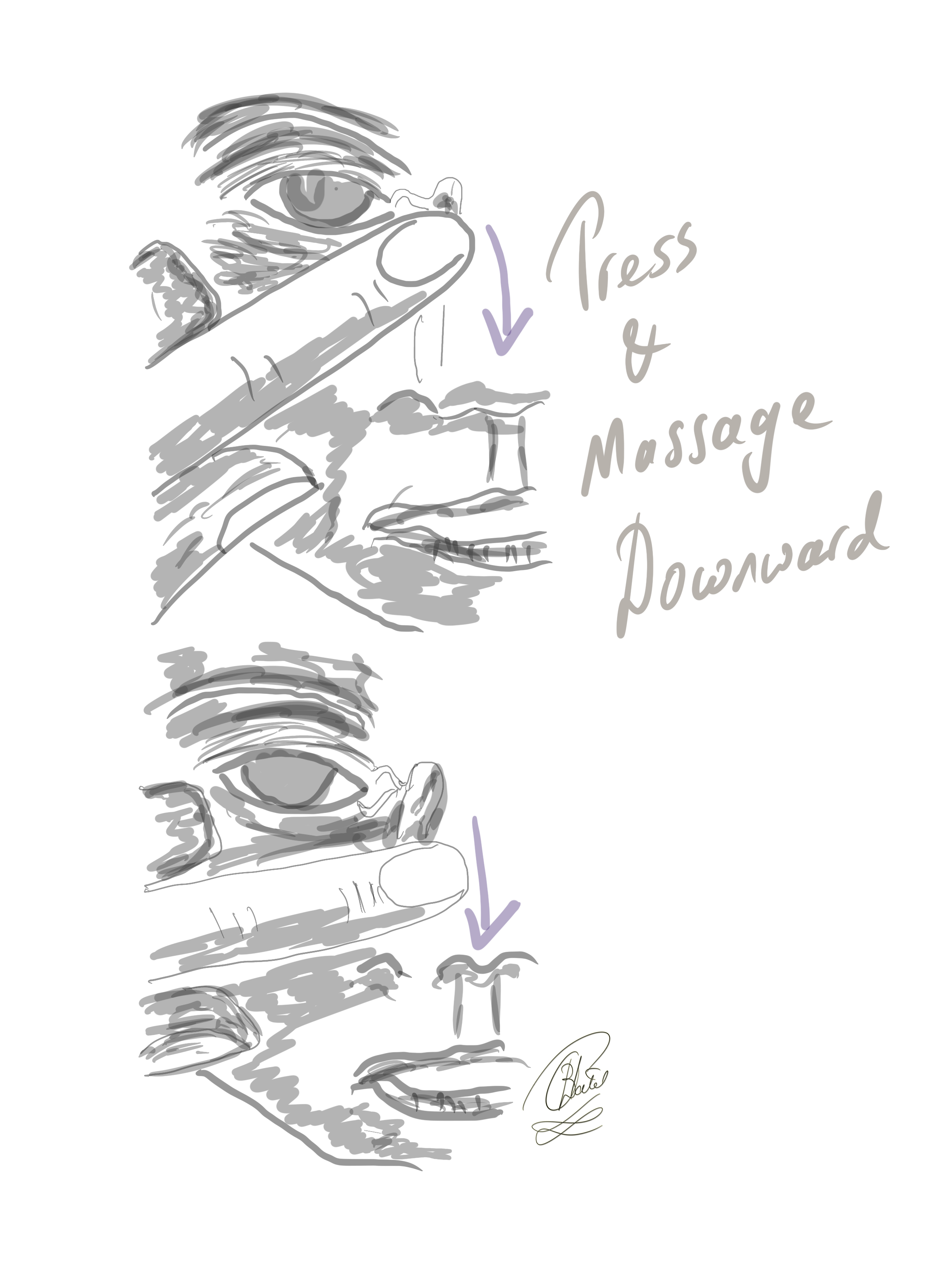

"The infant's head is held between the surgeon's knees in a manner similar to the method in vogue of inspecting the eyeball. Assuming that it is the right sac that is affected, he places his right thumb over the sac in a way to shut off the return flow through the puncta. This is done by holding the thumb sidewise, with the thumbnail outward and forming an acute angle with the plane of the iris. The edge of the thumb is now pressed down over the puncta, compress¬ ing it against the rim of the orbit; with this point of pressure maintained, the thumb is rotated to the right, at the same time pressing downward, abruptly, over the sac. The fluid, now being compressed by the thumb, transmits the pressure to the walls of the sac, which must give way at its weakest point, which happens to be the site of the nasal opening. Repeated cures after one manipulation of this sort, and no failures so far, extending over a period of seven years, convince me that the probe should never be resorted to except as a last resort. The salient points to be remembered are : (1) Pressure must be made over the sac only when it is distended; (2) care should be taken that the thumb is applied in such a way as to prevent régurgitation into the conjunctival sac, and (3) sudden pressure over the sac causes the retained fluid to burst through the persistent fetal membrane which separates the mucous lining of the nose from that of the nasal duct."

Kushner describes the hydrostatic massage technique as follows, "The technique consists of placing the index finger over the common canaliculus to block the exit of material through the lacrimal punctum and of stroking downward firmly to increase hydrostatic pressure within the nasolacrimal sac." Figure 1 He asked the parents to perform this with four to five strokes and four times a day. He treated his patients with this massage up to the time when the patient was six months old.

Our modification of the technique: We have found it best to massage both sides even if the tearing is only on one side as it makes it convenient to massage both lacrimal sacs with a pressure exerted downward by using the thumb on one side and the forefinger on the other side of the nose, over the respective lacrimal sacs. This is best performed with a fed child sitting on mum or dad's lap. We ask the parents to perform five to ten "strokes" four times a day. Although there is no agreement in the literature as to how long it should be done, we institute it at the first appointment and review the children every three to four months. (Video)

Complications

Excessive discharge and force applied to the medial canthal region can result in maceration of the skin. If so, the frequency of application is reduced, and topical moisturizers may be necessary.

Clinical Significance

This is a very useful technique that has been shown to allow resolution of the problem of CNLDO in children without surgical intervention. As it does not require any special instrumentation or medications, it should be used in all children seen with CNLDO.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

We are presenting details of this technique so that not only physicians but other clinic staff like technicians, physician assistants, and nurses may be familiar with it and can show the parents how to perform it. We ensure that everyone in our pediatric clinic is familiar with the technique, and each person is able to teach it to the parents. [Level 3]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Crigler Maneuver for Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction. In this technique, the finger is inwardly pressed against the lacrimal sac, and the massaging movement is directed downward to elevate hydrostatic pressure within the lacrimal sac and the nasolacrimal duct.

Contributed by BCK Patel, MD, FRCS

(Click Video to Play)

References

MacEwen CJ, Young JD. Epiphora during the first year of life. Eye (London, England). 1991:5 ( Pt 5)():596-600 [PubMed PMID: 1794426]

Sevel D. Development and congenital abnormalities of the nasolacrimal apparatus. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1981 Sep-Oct:18(5):13-9 [PubMed PMID: 7299606]

Lorena SH, Silva JA, Scarpi MJ. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in premature children. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2013 Jul-Aug:50(4):239-44. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20130423-01. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23614467]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlitsky SE. Update on congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. International ophthalmology clinics. 2014 Summer:54(3):1-7. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24879099]

Matta NS, Singman EL, Silbert DI. Prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2010 Oct:14(5):386-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2010.06.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21035062]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMatta NS, Silbert DI. High prevalence of amblyopia risk factors in preverbal children with nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2011 Aug:15(4):350-2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2011.05.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21907117]

CASSADY JV. Developmental anatomy of nasolacrimal duct. A.M.A. archives of ophthalmology. 1952 Feb:47(2):141-58 [PubMed PMID: 14894015]

Moscato EE, Kelly JP, Weiss A. Developmental anatomy of the nasolacrimal duct: implications for congenital obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2010 Dec:117(12):2430-4. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.030. Epub 2010 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 20656354]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeiss AH, Baran F, Kelly J. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: delineation of anatomic abnormalities with 3-dimensional reconstruction. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012 Jul:130(7):842-8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.36. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22410626]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePetris C, Liu D. Probing for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Jul 12:7(7):CD011109. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011109.pub2. Epub 2017 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 28700811]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNucci P, Capoferri C, Alfarano R, Brancato R. Conservative management of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1989 Jan-Feb:26(1):39-43 [PubMed PMID: 2915312]

Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y, Kinoshita S, Shiraki K, Iwaki M. The rate of symptomatic improvement of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in Japanese infants treated with conservative management during the 1st year of age. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2008 Jun:2(2):291-4 [PubMed PMID: 19668718]

Paul TO, Shepherd R. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: natural history and the timing of optimal intervention. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1994 Nov-Dec:31(6):362-7 [PubMed PMID: 7714699]

Paul TO. Medical management of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 1985 Mar-Apr:22(2):68-70 [PubMed PMID: 3989643]

Nelson LR, Calhoun JH, Menduke H. Medical management of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 1985 Sep:92(9):1187-90 [PubMed PMID: 4058881]

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. A randomized trial comparing the cost-effectiveness of 2 approaches for treating unilateral nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012 Dec:130(12):1525-33. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2853. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23229693]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYoung JD, MacEwen CJ, Ogston SA. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in the second year of life: a multicentre trial of management. Eye (London, England). 1996:10 ( Pt 4)():485-91 [PubMed PMID: 8944104]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, Repka MX, Melia BM, Beck RW, Atkinson CS, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, Khammar A, Morrison D, Quinn GE, Silbert DI, Ticho BH, Wallace DK, Weakley DR Jr. Primary treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction with nasolacrimal duct intubation in children younger than 4 years of age. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2008 Oct:12(5):445-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.03.005. Epub 2008 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 18595756]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeil BA. [Application of clinical technics and surgery in the diagnosis and treatment of lacrimal apparatus pathology]. Archivos de oftalmologia de Buenos Aires. 1967 Apr:42(4):73-8 [PubMed PMID: 5604492]

Jones LT. Anatomy of the tear system. International ophthalmology clinics. 1973 Spring:13(1):3-22 [PubMed PMID: 4724264]

PRICE HW. Dacryostenosis. The Journal of pediatrics. 1947 Mar:30(3):302-5 [PubMed PMID: 20290353]

Karti O, Karahan E, Acan D, Kusbeci T. The natural process of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction and effect of lacrimal sac massage. International ophthalmology. 2016 Dec:36(6):845-849 [PubMed PMID: 26948127]

Kushner BJ. Congenital nasolacrimal system obstruction. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1982 Apr:100(4):597-600 [PubMed PMID: 6896140]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStolovitch C, Michaeli A. Hydrostatic pressure as an office procedure for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2006 Jun:10(3):269-72 [PubMed PMID: 16814182]

Kim YS, Moon SC, Yoo KW. Congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: irrigation or probing? Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2000 Dec:14(2):90-6 [PubMed PMID: 11213741]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWelham RA, Hughes SM. Lacrimal surgery in children. American journal of ophthalmology. 1985 Jan 15:99(1):27-34 [PubMed PMID: 3966516]

Alagöz G, Serin D, Celebi S, Kükner S, Elçioğlu M, Güngel H. Treatment of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction with high-pressure irrigation under topical anesthesia. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2005 Nov:21(6):423-6 [PubMed PMID: 16304518]

Katowitz JA, Welsh MG. Timing of initial probing and irrigation in congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 1987 Jun:94(6):698-705 [PubMed PMID: 3627719]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKashkouli MB, Kassaee A, Tabatabaee Z. Initial nasolacrimal duct probing in children under age 5: cure rate and factors affecting success. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2002 Dec:6(6):360-3 [PubMed PMID: 12506276]

Kashkouli MB, Beigi B, Parvaresh MM, Kassaee A, Tabatabaee Z. Late and very late initial probing for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction: what is the cause of failure? The British journal of ophthalmology. 2003 Sep:87(9):1151-3 [PubMed PMID: 12928286]

Al-Faky YH. Nasal endoscopy in the management of congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Saudi journal of ophthalmology : official journal of the Saudi Ophthalmological Society. 2014 Jan:28(1):6-11. doi: 10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.11.002. Epub 2013 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 24526852]

Kouri AS, Tsakanikos M, Linardos E, Nikolaidou G, Psarommatis I. Results of endoscopic assisted probing for congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction in older children. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2008 Jun:72(6):891-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.02.024. Epub 2008 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 18440076]

Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group, Repka MX, Chandler DL, Bremer DL, Collins ML, Lee DH. Repeat probing for treatment of persistent nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2009 Jun:13(3):306-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.02.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19541274]

Schnall BM. Pediatric nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2013 Sep:24(5):421-4. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283642e94. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23846190]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNapier ML, Armstrong DJ, McLoone SF, McLoone EM. Congenital Nasolacrimal Duct Obstruction: Comparison of Two Different Treatment Algorithms. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2016 Sep 1:53(5):285-91. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20160629-01. Epub 2016 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 27486727]

Repka MX, Chandler DL, Holmes JM, Hoover DL, Morse CL, Schloff S, Silbert DI, Tien DR, Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Balloon catheter dilation and nasolacrimal duct intubation for treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction after failed probing. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2009 May:127(5):633-9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.66. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19433712]