Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality.[1] Although there have been significant improvements in the overall management of patients suffering from acute coronary syndromes (ACS), this entity is still associated with a relevant clinical burden.[2][3][4] In this context, the electrocardiogram (ECG) is central to the diagnostic process and treatment allocation, as early diagnosis allows for a timely reperfusion strategy. Though differentiation between ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) is pivotal, over the years, several electrocardiographic patterns associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) events have been described.[2][3][5][6][4]

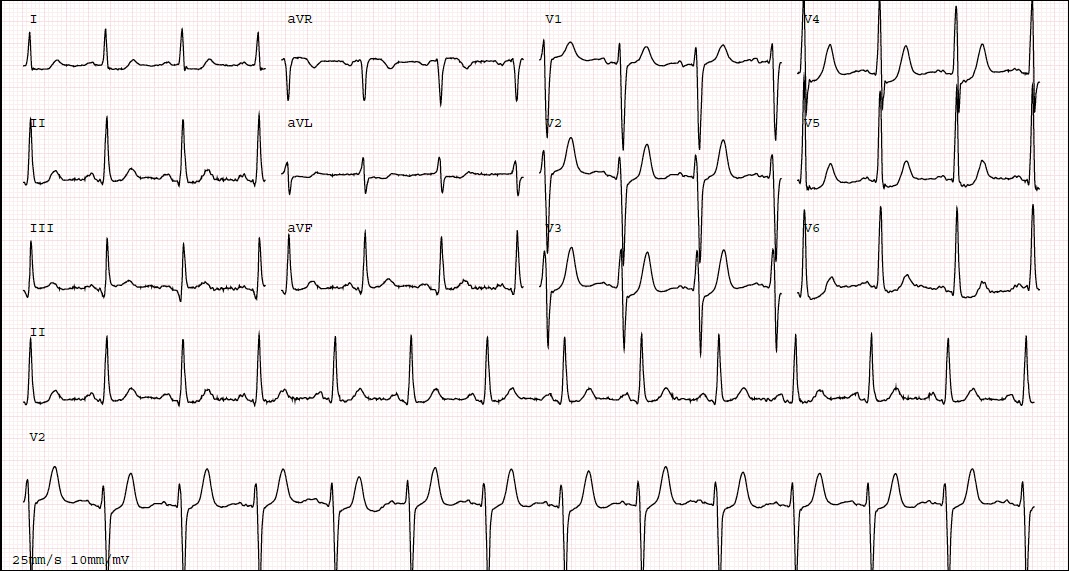

The de Winter electrocardiogram pattern is a finding that, in a proper setting, is highly suggestive of acute occlusion of the left anterior descending artery. This electrocardiogram finding consists of an ST-segment upsloping depression at the J point of 1 to 3 mm in leads V1 to V6, associated with tall, peaked positive T waves. The pattern is considered to be equivalent to an ST elevation as a clinical indication of myocardial infarction. Therefore, clinical recognition of this finding and the additional evaluation it should precipitate is critical to improving patient outcomes. Emergent consultation with a cardiologist should be undertaken when the de Winter electrocardiogram pattern is observed to allow for timely cardiac catheterization and primary percutaneous coronary intervention, if appropriate, to ensure appropriate reperfusion as per ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) guidelines.[2][5][7][4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The de Winter ECG pattern is associated with occlusion of the coronary arteries, most often the LAD. However, cases involving other coronary arteries (eg, the right coronary artery and the circumflex artery) have also been described.[8][9][10][11][12][13] Most cases reported occlusion due to atherosclerotic disease in line with other presentations of myocardial infarction,[5][12][5][8] though this pattern has also been described as due to a thromboembolic event.[13][5][12][5][8][13] The de Winter ECG pattern has also been noted without an acute epicardial occlusion after a percutaneous coronary intervention, hypothesized as associated with impaired microvascular perfusion.[12]

Epidemiology

The de Winter electrocardiogram pattern is an infrequent presentation, reported to occur in 2% to 3.4% of patients with anterior myocardial infarction.[8][10][14][15] Because the de Winter electrocardiogram pattern relates to patients presenting with ACS, the risk factors associated with this pattern are similar to those of ischemic heart disease (eg, increased age, smoking, dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and obesity).[1][2][3][14] In some studies, male patients were more likely to present with this pattern, and some authors have reported that individuals with this pattern tend to be younger than those who present with an anterior STEMI.[14][15][10][15]

Pathophysiology

Though the specific pathophysiology associated with the de Winter ECG pattern is unclear, several potential mechanisms have been proposed. One that has garnered substantial interest relates to subendocardial ischemia, with ensuing subendocardial, as compared to subepicardial, action potentials at a hyperacute stage of the event before transmural ischemia becomes predominant.[16][14][17][18] Another theory is that collateral circulation causes the de Winter ECG pattern.[18][19] This latter hypothesis, however, does not fully explain reports of this presentation in patients without adequate collateral circulation.[8][16][14] Other proposed mechanisms include anatomical variants in the Purkinje fibers and myocardial metabolism downregulation.[8][11][17] A contemporary cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study by Zorzi et al highlighted the potential interplay of several mechanisms (eg, differential action potential expression and collateral circulation) resulting in the de Winter ECG pattern.[18]

History and Physical

Given that the de Winter ECG pattern is generally associated with an ACS, patients frequently will present with a medical history positive for heart disease risk factors, including a family or personal history of heart disease, hypertension, or dyslipidemia. Clinical features are also consistent with ACS (eg, oppressive acute chest pain and shortness of breath).[2][5][16][11][19][4]

Because the de Winter ECG pattern is often associated with a hyperacute stage of myocardial infarction (MI), physical examination can be unremarkable. However, some patients may present with diaphoresis and ongoing discomfort associated with acute symptomatology in the setting of ACS.[16][11][13][18][19] Findings on physical examination may also vary, as detailed by the Killip classification system, which was developed to guide the clinical assessment of patients with myocardial infarction.[2][20][2]

- Killip class I: patients without any clinical sign of heart failure

- Killip class II: patients with crackles or rales in the lungs, elevated jugular venous pressure, and an S3 gallop

- Killip class III: patients with evident acute pulmonary edema

- Killip class IV: patients with cardiogenic shock or hypotension (ie, a systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg) and signs of low cardiac output (eg, oliguria, cyanosis, or impaired mental status)

Evaluation

The de Winter ECG pattern, as proposed in the seminal article by De Winter et al, consists of an ST-segment upsloping depression at the J point of 1 to 3 mm in leads V1 to V6, associated with tall and peaked positive T waves.[8] Additionally, most individuals present with a 1 to 2 mm ST-segment elevation in lead aVR.[8] Other possible findings include loss of R wave progression in the precordial leads and QRS complexes of normal duration or only slightly widened.[8] (see Image. The de Winter ECG pattern)

However, strict criteria defining the de Winter ECG pattern remain elusive, as elegantly reported in a systematic review by Morris et al which showed differences in categorization among studies.[9][10] In this review, upsloping depression of the ST-segment focusing on lead V3 and associated with upright T waves were consistently reported, whereas most individuals also had poor progression of the R wave as well as ST-segment elevation in lead aVR.[9] Interestingly, although initially described as comprising a static pattern, which was also noted in other studies, there are reports describing a potential temporal evolution as the ischemic event unfolds.[9][8][21][15][19]

Cardiac biomarkers, specifically high-sensitivity cardiac troponin (hs-cTn), should be assessed, though as stressed in contemporary guidelines, this should not delay the reperfusion strategy.[2][5][4] This pattern is associated with a hyperacute presentation, and therefore, clinicians should be aware that hs-cTn may be within the normal range or only mildly elevated initially.[16][22] Given the differential diagnosis, serum potassium levels may be considered, though this should not delay the reperfusion strategy.[8][16][23]

Treatment / Management

In patients with ACS risk factors or clinical features, the presence of the de Winter ECG pattern should lead to a high degree of suspicion for LAD artery occlusion.[5][10][19] Emergent consultation with a cardiologist should be undertaken, thus allowing early referral for cardiac catheterization and primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) if appropriate to ensure appropriate reperfusion as per STEMI guidelines.[2][3][8][10][19][4] Additionally, optimized medication, including aspirin, a P2Y12 inhibitor, and anticoagulation, should be implemented as the interventional cardiologist recommends.[2][3][4][24] After adequate reperfusion, patients should be admitted to a monitored coronary care or intensive cardiac care unit, with subsequent management and ancillary testing recommended by current guidelines.[2][3][5][4](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Though most cases of this pattern are associated with an acute occlusion of the LAD artery, similar changes in repolarization can also be present in other clinical scenarios. Among these, hyperkalemia should be considered, although this condition can typically be differentiated by a distinct clinical presentation and T waves that tend to be narrow and sharply peaked.[22][23][25] Moreover, as discussed by Xu et al, tachycardia can also be associated with the upsloping depression of the ST-segment and cTn elevation.[14]

Prognosis

The de Winter ECG pattern is associated with acute coronary artery occlusion, most notably the LAD.[8][9] As such, early recognition and treatment allocation are critical to allow adequate reperfusion and improve the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with a large anterior MI.[2][26][4]

Deterrence and Patient Education

As early diagnosis plays a prominent part in the management of individuals with an ACS and given the potential adverse outcomes associated with an acute LAD occlusion, reducing any barriers to seeking medical care is essential. Therefore, patients should be counseled on the most common symptoms associated with ACS and the importance of seeking urgent medical evaluation.[2][26][4] In this way, patient delays may be avoided, thus reducing total ischemic time.[2][4]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The de Winter electrocardiogram pattern highly suggests acute occlusion of the LAD artery.[8][9][10] Given this background, all members involved in the interprofessional care process of individuals presenting with acute chest pain should be able to identify this ECG finding expertly, thus streamlining the diagnostic and therapeutic process of this challenging and high-risk subset of patients. Healthcare practitioners in the many departments that may encounter these patients, including primary care, emergency room, cardiology, and internal medicine, should recognize that further evaluation is warranted when the de Winter electrocardiogram pattern is present, leading to improved recognition of potential abnormalities. Additionally, electrocardiogram technicians, cardiac procedural staff, and pharmaceutical clinicians are often needed to provide care to these patients when diagnosed with acute coronary syndromes. As a result, clinicians can use this finding to help guide treatment strategies and improve patient outcomes.[2][5][10][26][4]

Media

References

Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale CP, Torbica A, Lettino M, Petersen SE, Mossialos EA, Maggioni AP, Kazakiewicz D, May HT, De Smedt D, Flather M, Zuhlke L, Beltrame JF, Huculeci R, Tavazzi L, Hindricks G, Bax J, Casadei B, Achenbach S, Wright L, Vardas P, European Society of Cardiology. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular Disease Statistics 2019. European heart journal. 2020 Jan 1:41(1):12-85. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz859. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31820000]

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, Caforio ALP, Crea F, Goudevenos JA, Halvorsen S, Hindricks G, Kastrati A, Lenzen MJ, Prescott E, Roffi M, Valgimigli M, Varenhorst C, Vranckx P, Widimský P, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal. 2018 Jan 7:39(2):119-177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28886621]

O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 Jan 29:61(4):e78-e140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. Epub 2012 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 23256914]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceByrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, Barbato E, Berry C, Chieffo A, Claeys MJ, Dan GA, Dweck MR, Galbraith M, Gilard M, Hinterbuchner L, Jankowska EA, Jüni P, Kimura T, Kunadian V, Leosdottir M, Lorusso R, Pedretti RFE, Rigopoulos AG, Rubini Gimenez M, Thiele H, Vranckx P, Wassmann S, Wenger NK, Ibanez B, ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. European heart journal. 2023 Oct 12:44(38):3720-3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37622654]

Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, White HD, Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Oct 30:72(18):2231-2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. Epub 2018 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 30153967]

Vilela EM, Sampaio F, Dias T, Barbosa AR, Primo J, Caeiro D, Fonseca M, Ribeiro VG. A critical electrocardiographic pattern in the age of cardiac biomarkers. Annals of translational medicine. 2018 Apr:6(7):133. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.02.13. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29955593]

Sanaani A, Yandrapalli S, Jolly G, Paudel R, Cooper HA, Aronow WS. Correlation between electrocardiographic changes and coronary findings in patients with acute myocardial infarction and single-vessel disease. Annals of translational medicine. 2017 Sep:5(17):347. doi: 10.21037/atm.2017.06.33. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28936441]

de Winter RJ, Verouden NJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA, Interventional Cardiology Group of the Academic Medical Center. A new ECG sign of proximal LAD occlusion. The New England journal of medicine. 2008 Nov 6:359(19):2071-3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0804737. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18987380]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorris NP, Body R. The De Winter ECG pattern: morphology and accuracy for diagnosing acute coronary occlusion: systematic review. European journal of emergency medicine : official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2017 Aug:24(4):236-242. doi: 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000463. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28362646]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Winter RW, Adams R, Amoroso G, Appelman Y, Ten Brinke L, Huybrechts B, van Exter P, de Winter RJ. Prevalence of junctional ST-depression with tall symmetrical T-waves in a pre-hospital field triage system for STEMI patients. Journal of electrocardiology. 2019 Jan-Feb:52():1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2018.10.092. Epub 2018 Oct 18 [PubMed PMID: 30476631]

Tsutsumi K, Tsukahara K. Is The Diagnosis ST-Segment Elevation or Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction? Circulation. 2018 Dec 4:138(23):2715-2717. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.037818. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30571261]

Chen S, Wang H, Huang L. The presence of De Winter electrocardiogram pattern following elective percutaneous coronary intervention in a patient without coronary artery occlusion: A case report. Medicine. 2020 Jan:99(5):e18656. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018656. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32000371]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlahmad Y, Sardar S, Swehli H. De Winter T-wave Electrocardiogram Pattern Due to Thromboembolic Event: A Rare Phenomenon. Heart views : the official journal of the Gulf Heart Association. 2020 Jan-Mar:21(1):40-44. doi: 10.4103/HEARTVIEWS.HEARTVIEWS_90_19. Epub 2020 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 32082500]

Xu J, Wang A, Liu L, Chen Z. The de winter electrocardiogram pattern is a transient electrocardiographic phenomenon that presents at the early stage of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Clinical cardiology. 2018 Sep:41(9):1177-1184. doi: 10.1002/clc.23002. Epub 2018 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 29934946]

Verouden NJ, Koch KT, Peters RJ, Henriques JP, Baan J, van der Schaaf RJ, Vis MM, Tijssen JG, Piek JJ, Wellens HJ, Wilde AA, de Winter RJ. Persistent precordial "hyperacute" T-waves signify proximal left anterior descending artery occlusion. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2009 Oct:95(20):1701-6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.174557. Epub 2009 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 19620137]

Vilela EM, Caeiro D, Primo J, Braga P. A pivotal electrocardiographic presentation: reading between the lines. The Netherlands journal of medicine. 2019 Oct:77(8):297 [PubMed PMID: 31814579]

Gorgels AP. Explanation for the electrocardiogram in subendocardial ischemia of the anterior wall of the left ventricle. Journal of electrocardiology. 2009 May-Jun:42(3):248-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2009.01.002. Epub 2009 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 19264324]

Zorzi A, Perazzolo Marra M, Migliore F, Tarantini G, Iliceto S, Corrado D. Interpretation of acute myocardial infarction with persistent 'hyperacute T waves' by cardiac magnetic resonance. European heart journal. Acute cardiovascular care. 2012 Dec:1(4):344-8. doi: 10.1177/2048872612466537. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24062926]

de Winter RW, Adams R, Verouden NJ, de Winter RJ. Precordial junctional ST-segment depression with tall symmetric T-waves signifying proximal LAD occlusion, case reports of STEMI equivalence. Journal of electrocardiology. 2016 Jan-Feb:49(1):76-80. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2015.10.005. Epub 2015 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 26560436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHashmi KA, Adnan F, Ahmed O, Yaqeen SR, Ali J, Irfan M, Edhi MM, Hashmi AA. Risk Assessment of Patients After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction by Killip Classification: An Institutional Experience. Cureus. 2020 Dec 21:12(12):e12209. doi: 10.7759/cureus.12209. Epub 2020 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 33489617]

Fiol Sala M, Bayés de Luna A, Carrillo López A, García-Niebla J. The "De Winter Pattern" Can Progress to ST-segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Revista espanola de cardiologia (English ed.). 2015 Nov:68(11):1042-3. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2015.07.006. Epub 2015 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 26410027]

Carrington M, Santos AR, Picarra BC, Pais JA. De Winter pattern: a forgotten pattern of acute LAD artery occlusion. BMJ case reports. 2018 Nov 8:2018():. pii: bcr-2018-226413. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226413. Epub 2018 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 30413454]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLevis JT. ECG Diagnosis: Hyperacute T Waves. The Permanente journal. 2015 Summer:19(3):79. doi: 10.7812/TPP/14-243. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26176573]

Galli M, Andreotti F, Sabouret P, Gragnano F. 2023 ESC Guidelines on ACS: what is new in antithrombotic therapy? European heart journal. Cardiovascular pharmacotherapy. 2023 Nov 2:9(7):595-596. doi: 10.1093/ehjcvp/pvad065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37738449]

Rafique Z, Chouihed T, Mebazaa A, Frank Peacock W. Current treatment and unmet needs of hyperkalaemia in the emergency department. European heart journal supplements : journal of the European Society of Cardiology. 2019 Feb:21(Suppl A):A12-A19. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/suy029. Epub 2019 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 30837800]

Kontos MC, Gunderson MR, Zegre-Hemsey JK, Lange DC, French WJ, Henry TD, McCarthy JJ, Corbett C, Jacobs AK, Jollis JG, Manoukian SV, Suter RE, Travis DT, Garvey JL. Prehospital Activation of Hospital Resources (PreAct) ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI): A Standardized Approach to Prehospital Activation and Direct to the Catheterization Laboratory for STEMI Recommendations From the American Heart Association's Mission: Lifeline Program. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020 Jan 21:9(2):e011963. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.011963. Epub 2020 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 31957530]